The staff of the Plains Indian Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West answer these frequently asked questions about glass beads, tipis, and more.

A: Since ancient times, Indian people have traded with neighboring tribes and distant groups alike. Plains Indians, located at the center of vast coast-to-coast networks, mediated between cultural groups exchanging raw materials, traditional arts, and food surpluses. Trade relationships were often cemented through adoption or marriage, resulting in influential and broadly dispersed alliances. By the mid-1800s, when Europeans arrived on the Plains, their trade goods such as glass beads, colored cloth, iron implements, and guns had preceded them along well-established and dynamic Native trade routes.

Most of the beads introduced to Plains Indian peoples by Europeans were made of glass, a material previously unknown to the Native cultures. When glass beads were introduced as a trade item, they were widely sought by Native peoples for their colors and ease of use. They often replaced Indian-made beads of bone, shell, copper, and stone. Beads were important for early trade items because they were compact and easily transportable.

“Pony” beads, so named because they were transported by traders with pony pack trains, arrived in the early 1800s. Simple, bold designs make good use of the pony bead’s large size (2 – 4 millimeters) and limited palette of white, black, and blue. Blue beads were particularly popular in the Plains, possibly because that color was rare in Native dye sources.

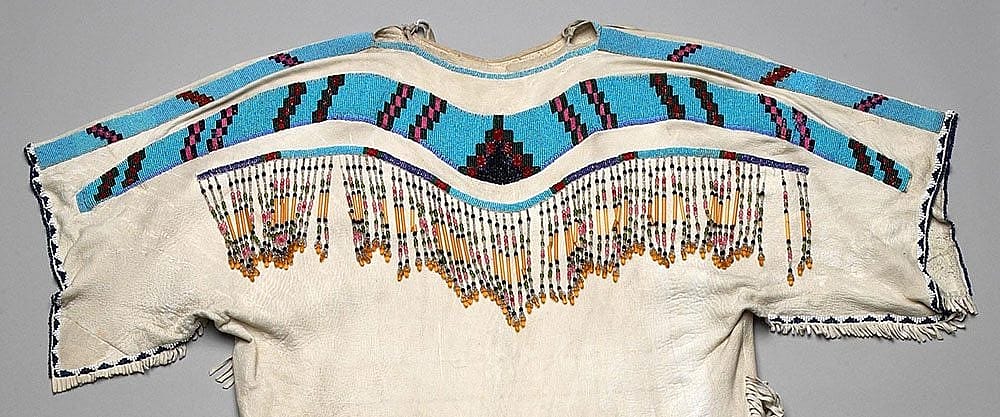

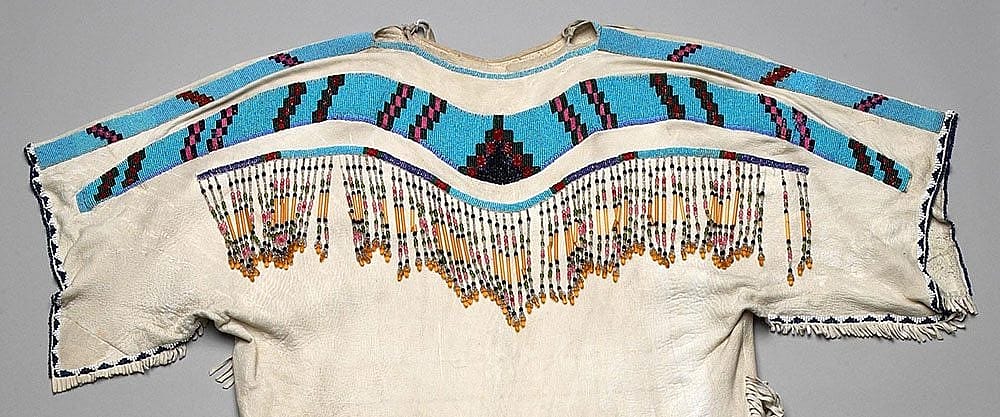

Beginning about 1840, colorful, tiny seed beads, usually two millimeters or less in diameter, were traded in bulk, the result of the standardization of manufacturing techniques in Venice and Bohemia, which made it possible to produce beads of uniform size, shape, and color. Plains tribes developed preferences for particular bead colors, such as the Crow people favoring turquoise and pink. After 1870, translucent beads in even richer hues and more varied shapes became popular. Beadworking continues to be an important part of Native American culture, art, and business. There are numerous examples of fine, contemporary beadworking in the Plains Indian Museum Collection.

A: Prior to European contact, North American Indian peoples typically made beads from local materials, however they eagerly sought imported stones, shells, and metals to make rare beads that would be prestigious.

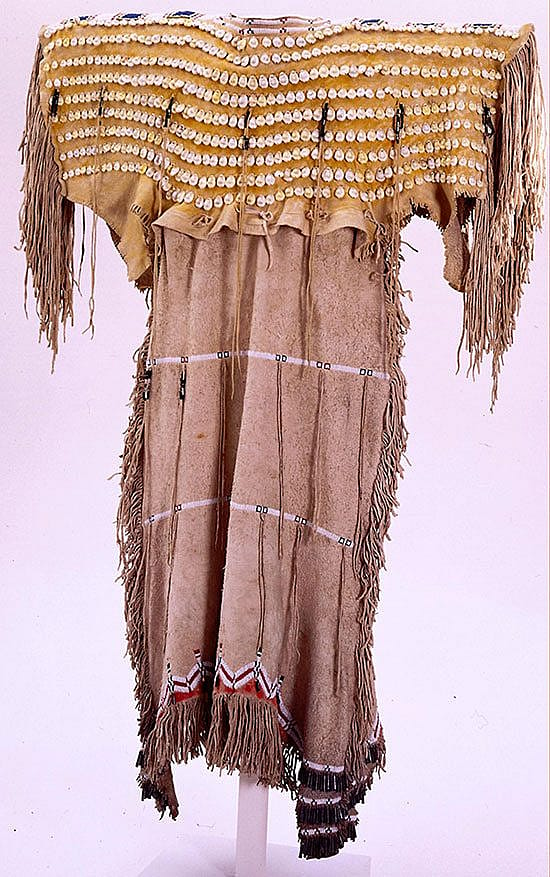

Elk teeth: Only the two eye teeth of an elk, the ivories, were used for garment decoration. In the mid-nineteenth century, one hundred elk teeth would buy a good horse. The Crow girl’s dress pictured at right is covered with bone carved to look like elk teeth; it makes a beautiful decoration on a wool dress.

The magnificent Kiowa dress yoke pictured below is made of tanned deer hide and is covered in elk teeth, seed beads, and tubular beads.

The number of teeth…symbolized the prowess of the husband-provider. If a wife and all her female children were attired in these dresses, it was a sign of a family of means. –Mardell Hogan Plainfeather, Crow, 1992

Cowrie shells: The cowrie shells embellishing the yoke of this formal Southern Cheyenne dress pictured at right originated in the Indian and South Pacific Oceans. They arrived on the Plains via the ancient intercontinental trade network. Long after manufactured trade goods were available, seashells remained a popular garment decoration.

Dentalium shells: Dentalium shells from the Pacific Northwest were traded throughout the Plains. Dentalium shells had both monetary and decorative value. The shell was distributed through intertribal barter from the Pacific to the Arctic. Native people used and esteemed shell beads above all others, and the raw material often traveled great distances.

Hair pipes: Cylindrical beads, called “hair pipes,” were a popular trade item on the Plains, prized for use in breastplates, necklaces, and hair ornaments. The beads were originally made by Southeastern tribes from conch shells, but only became widely available on the Plains when a New Jersey entrepreneur mass-produced them for the lucrative Indian trade, replicating them in bone turned on a lathe.

A: The Plains Indian lodge, or tipi, is one of the most beautiful and practical shelters ever invented. It is easy to put up and take down, and resistant to wind and rain. The tilted cone is steeper at the back, with an adjustable smoke hole extending down the front sloping side, and flaps that can be moved to regulate the draft and be readjusted if bad weather conditions arise. A lodge always faces east to greet the morning sun.

Crow lodges are constructed around four main poles, as opposed to the tripod that other tribes use. These foundation poles are tied together with a piece of rope and then raised. Poles are placed equidistantly around the foundation to form the framework of the tipi. The longer the poles, the larger the tipi. The tipi cover is tied to the last pole, so they both go up together, and placed at the back.

Next, the cover is wrapped from the back around the sides to the front and fastened above the doorway with pegs. The cover is drawn in tight and the bottom edge staked to the ground. Two long poles on either side of the outside of the tipi control the smoke flaps.

After the 1880s, when the traditional bison hide became less available, canvas was used as an alternative for lodge covers. The canvas lodge on exhibit in the Plains Indian Museum has the sides rolled up for the summer, to cool the interior. In the winter, the layers of skins on the floor, the liner, and a fire make a lodge warm, comfortable, and weather-resistant.

Today, tipis are used at gatherings, ceremonies, powwows, and large events such as Crow Fair. Since 1904, the Fair has been held on the third week of August at Crow Agency, Montana. Crow Fair is a week full of powwows, rodeos, parades, giveaways, horse races, and so much more. For good reason, the Crow Fair encampment is called “Teepee Capital of the World.” As far as the eye can see, triangles of white canvas spread across the countryside welcoming people from all over the world to learn about, and experience, the Apsaalooke people.