Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall 2008

Yellowstone’s Burning Issue: The Fires 20 Years Later

By Charles R. Preston, PhD

Twenty years ago, raging wildfires affected nearly 800,000 acres within the boundaries of Yellowstone National Park, and a total of more than two million acres throughout the Greater Yellowstone region. The flames also ignited a national debate about the causes and consequences of wildfire in natural systems and the fire management policy of the National Park Service. Mass media reports of the fires were peppered with the words “devastating,” “destroyed,” “disaster,” and “death,” referring to the effects of fires on the natural landscape and wildlife of Yellowstone. These words both represented and helped reinforce the general public’s perception of wildland fire as a terrible agent of mass destruction.

An extreme landscape makeover in Yellowstone

Certainly, wildfires like those seen in Yellowstone in 1988 can devastate human activities, plans, and economies, and can destroy human life and property. But they are also as integral to the character of the Yellowstone landscape as are earthquakes, volcanoes, wind, and snowfall.

Fire is one of the major forces that has determined which plants and animals occupy the Greater Yellowstone region ever since the last great glaciers retreated. The lodgepole pine, Douglas fir, Engelmann spruce and subalpine fir forests that cover most of Yellowstone National Park and the surrounding landscape have been shaped and reshaped by fire for thousands of years. The age of the forest stand, tree species composition, and weather are critical elements that drive the timing and severity of fires.

In 1988, roughly one-third of Yellowstone’s forests were more than 250 years old. At this age, they were reaching a point where they were most vulnerable to natural, stand-replacing fires that would, in effect, perform an “extreme landscape makeover.” All that was needed to initiate the process was an especially dry, hot, windy summer.

No hint of historic fire season

The spring of 1988 began with no hint of the factors necessary for a drastic makeover. April and May were wet months, with 155 and 181 percent, respectively, of normal rainfall recorded at Mammoth Hot Springs in the northwest corner of the park. Native grasses and other herbaceous plants formed a lush, green cover through much of the region.

But virtually no precipitation fell in June. Dry thunder-and-lightning storms moved across the region, igniting at least eighteen fires. In accordance with the park’s fire management plan, these nature-caused fires were evaluated and allowed to burn. As is common with backcountry wildfires, eleven of these blazes burned themselves out; others continued to burn, but created no immediate threat to human life or property.

Even with June’s dry weather, however, there was little reason to believe that a historic fire season was eminent. For example, in the fifteen years immediately prior to 1988, 84 percent of nature-caused fires allowed to burn in the park were naturally extinguished after burning less than five acres. Secondly, there was reason to expect some relief from the dry June conditions because July had been a wet month in the preceding several years. The same was predicted for 1988. In fact, Mammoth Hot Springs recorded more than three times the normal July rainfall in 1987.

The right ingredients for wildfire in Yellowstone

However, 1988 was drastically different: It became the driest Yellowstone summer since record-keeping began in 1886. Little rain fell in July, and by the middle of the month, the lush green grass of early summer and other plant cover had become dry and brown. Some standing and fallen dead timber registered less than 8 percent moisture content—lower than kiln-dried lumber! Winds and ambient temperatures also picked up, drying the vegetation further and injecting existing blazes with vigor.

By July 15, 1988, it became clear that conditions were ripe for a massive wildfire event. The park’s natural fire policy was suspended, and no new naturally-caused fires were allowed to burn without challenge. Under fire management policy, human-caused fires were always suppressed. An exception was made for lightning-caused fires that ignited near, and were burning into, existing fires.

Nonetheless, fires covered approximately 17,000 acres within the park by July 21, and all fires were being suppressed as fully as resources would allow. But the severe weather conditions (extremely dry, with little humidity even at night; high temperatures; high winds; and high fuel accumulation) presented insurmountable obstacles to fire containment. High winds sometimes blew sparks and firebrands a mile ahead of advancing flames, igniting new fires. This “spotting” phenomenon made the 1988 fires even more difficult to control or even contain.

Wildfire tally

Eventually, more than $120 million was spent fighting the fires, with roughly 25,000 people involved. More acres burned on August 20, 1988 (frequently called “Black Saturday”), than had burned in a single twenty-four-hour period during any decade since 1872. Core firefighting activities were focused on containment of the outer perimeters and on protecting lives and property. Despite all efforts, fires continued to advance inside and outside park boundaries until rain and snow began falling in September. Heavy snows finally extinguished the last of the flames in November.

The 1988 complex of blazes that affected Yellowstone National Park lands included forty-two fires caused by lightning and nine fires caused by humans. A total of 248 fires started throughout the Greater Yellowstone region in 1988. Of the 793,880 acres that burned inside park boundaries, an estimated 500,000 were affected by fires that began outside the park. The single largest of these, the North Fork fire, was ignited when a woodcutter just outside park boundaries tossed a smoldering cigarette into dry vegetation. That fire was fought from the outset, but it could not be suppressed.

Given the scope and duration of the 1988 Yellowstone fires, it is remarkable that only two fire-related human fatalities were reported. On September 12, Don Kuykendall died when the fire-crew transport plane he was piloting crashed on its return to Jackson, Wyoming. Bureau of Land Management employee Ed Hutton died on October 11 when a falling tree struck him during cleanup operations in the Shoshone National Forest. The fires destroyed between sixty-five and seventy park structures, and most of these were replaced or rehabilitated by the end of 1989.

Wildfire and wildlife

In addition, the fires affected different species of Yellowstone animals and plants in various ways and on different time scales. Dead trees left standing provided nest sites for open-country, cavity-nesting birds such as mountain bluebirds. These tree snags also provided ideal hunting perches with panoramic views for many raptors. On the other hand, birds and mammals of old-growth forests, such as boreal owls and American martens, saw their habitat decline with the fires.

At least 350 elk, 36 deer, 12 moose, 6 black bears, and 9 bison died as an immediate and direct consequence of the fires. During the winter following the fires, most ungulates (hoofed animals) suffered higher-than-average mortality. Wildlife biologists attributed the increased mortality for mule deer and pronghorn more to the extreme summer drought and severe winter of 1988 – 1989 than to the fires, as their winter range was not affected significantly by the fires. It remains unclear what percentage of increased elk mortality could be attributed to the fires. Summer drought, severe winter weather, high herd density, and higher-than-average hunter harvest all probably played some role in the 40-percent mortality rate in the elk population that year.

Bald eagles, ravens, bears, and small carnivores no doubt benefited from the boon of ungulate carcasses during the winter and spring after the fires. Many raptor and medium-to-small carnivore species also likely benefited from less ground cover to hide rodents and other small mammal prey in the first seasons following the fires.

The distribution of grizzly bear foraging activity changed interestingly in the years immediately following the fires. Bears spent more time foraging on plants in burned than unburned areas and spent as much as 63 percent less time foraging in some whitebark pine areas affected by fire. Overall, grizzly bear numbers showed no clear response to the 1988 fires.

The moose is the only large mammal to exhibit a long-term decline in, presumably in response to the fires. These fires killed large expanses of spruce and fir, a critical source of winter forage for moose. Given suitable climatic conditions, these spruce-fir stands may again dominate some Yellowstone landscapes through the natural process of forest succession. But in the meantime, most of the open, burned sites formerly covered by spruce-fir provide more suitable conditions for early colonization by lodgepole pine.

A new forest

Many of the forests that burned in 1988 have already been colonized or repopulated by lodgepole pine seedlings along with a wide diversity of grasses and other non-woody plants. The distribution and growth rate of lodgepole pine following a fire depends on the severity of the burn, soils, sun exposure, seed source, moisture availability, and other characteristics of the site. Many mature lodgepole pine trees produce cones that are sealed tightly by resin. These cones only open with high temperatures, releasing their seeds to the soil. Thus, pre-burn sites with a high number of pines containing these resin-sealed cones contain an excellent seed source following a fire.

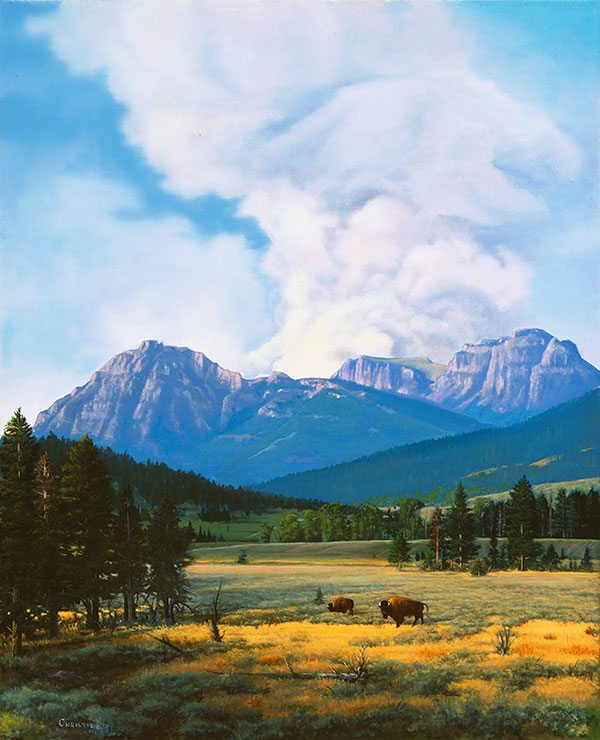

Lodgepole seedlings grow especially well in open areas with good exposure to sun. In some areas, the growing lodgepole pines will eventually create shade for their own seedlings and give way to the more shade-loving spruce and fir trees. In this way, wildfire helps create a mosaic landscape covered by a patchwork of diverse plant communities of different ages and different species composition. Increased plant diversity supports increased animal diversity.

One big surprise that scientists discovered in the aftermath of the 1988 fires was that aspen trees sprang up from seeds in burned areas. This refuted the conventional wisdom that aspen clones in the Northern Rockies did not reproduce by seed, but instead only sprouted from roots of burned trees. In contrast to that opinion, seedling aspen stands became well-established in many areas far from the nearest known aspen clone.

Although they thrived in the first decade after the 1988 fires, many of these aspen stands have now failed. The current warm, dry climate may explain why these aspen seedlings have not survived. It might also help account for the general decline of aspen throughout Yellowstone and the Northern Rockies over the last eighty years or so. In addition, foraging pressure from the large ungulate population may play a role in the drop in the number of aspen stands.

Twenty years later

Clearly, Yellowstone was not destroyed by the fires of 1988. The landscape and wildlife populations were reshaped by these and subsequent fires as they have been for thousands of years—a testimony to just how dynamic nature can be.

Because wildfires carry enormous potential to harm human communities, management agencies walk a fine line between allowing natural processes to continue to shape wildland areas and protecting human life, property, and economies bordering wildlands. The current National Fire Plan, developed in part from information gleaned from the 1988 Yellowstone experience, emphasizes cooperation among federal agencies in managing wildland fires. It recognizes wildland fire as an essential ecological process and natural change agent which should be allowed to burn when safe to do so. On the other hand, the plan also calls for reduction of fuels as feasible and for aggressive and prompt suppression of fires that are considered a potential threat to human life and property.

Whether the scorching destiny that visited the Greater Yellowstone region in 1988 could have been changed significantly by more aggressive or more proficient firefighting before or after July 15, 1988, will no doubt be debated for decades to come. But twenty years after that fateful summer, wildfire is now widely recognized and accepted as a fundamental force of nature that shapes and reshapes the landscapes, wildlife, and human lifestyles of the Greater Yellowstone region.

About the author

Charles R. Preston, PhD, is the Founding Curator of the Draper Natural History Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. Prior to that position, his career path included Chairman of the Department of Zoology at the Denver Museum of Natural History, Associate Professor of Biological Sciences at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, and adjunct faculty appointments in biology and environmental science at the University of Colorado (Boulder and Denver), environmental policy and management at the University of Denver, and biological sciences at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Preston is now Senior Scientist and Curator Emeritus of the Draper.

A zoologist and wildlife ecologist by training, Preston currently focuses his research on human dimensions of wildlife management and conservation in North America, especially the Greater Yellowstone region and the American West. A prolific writer, he has authored four books and more than sixty scholarly and popular articles on these subjects.

Post 004