The Mandan

The Mandan historically lived along the banks of the Missouri River and two of its tributaries—the Heart and Knife Rivers—in present-day North and South Dakota. Speakers of Mandan, a Siouan language, the people developed a settled culture in contrast to that of more nomadic tribes in the Great Plains region.

The Mandan presently call themselves Nueta (Rų́ʔeta), which is translated as “ourselves” or “our people.”

Prior to settling on the Heart and Knife Rivers as early as the seventh century, the Mandan may have migrated from the mid-Mississippi River and Ohio River valleys, then going north towards the Missouri River Valley, where they first encountered by Europeans.

The Mandan established permanent villages featuring large, round, earth lodges some 40 feet (12 meters) in diameter, arranged around a central ceremonial plaza. The villages were set within naturally defensive features, like ravines or riverbanks, or they built protective walls or ditches.

While the buffalo was essential to the daily life of the Mandan, it was supplemented by agriculture and trade. Women controlled the bountiful gardens that were near the villages, which brimmed with corn, squash, and beans. Corn has always been the mainstay of Mandan agriculture, remaining a vital symbol of creation, revitalization and survival. After horses were acquired in the mid-eighteenth century from the Apache, they were used to expand the Mandan hunting territory to the Plains.

The French Canadian trader Sieur de la Verendrye first met the Mandan in 1738. At this time, there were 15,000 Mandan residing in the nine villages on the Heart River. Soon a trading link between the French and Native people of the region was established; and the Mandan served as middlemen in the market of trading furs, horses, firearms, crops, and buffalo products.

In 1804, when Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark and the Corps of Discovery visited the tribe; the number of Mandan had been greatly reduced by smallpox epidemics and warring bands of Assiniboine, Lakota, and Arikara. (Later they joined with the Arikara in defense against the Lakota.) The nine villages had been consolidated into two. The Lewis and Clark expedition met with such hospitality in the Upper Missouri River villages that the expedition wintered over. In honor of their hosts, the expedition dubbed the settlement they constructed Fort Mandan. It was here that Lewis and Clark first met Sacagawea, a Shoshone woman who had been captured. Sacagawea assisted the expedition with information and translating skills as they travelled westward towards the Pacific Ocean. Upon their return to the Mandan villages, Lewis and Clark took the Mandan Chief Sheheke (Coyote or Big White) with them to Washington to meet with President Thomas Jefferson. In 1812, Sheheke was killed in battle.

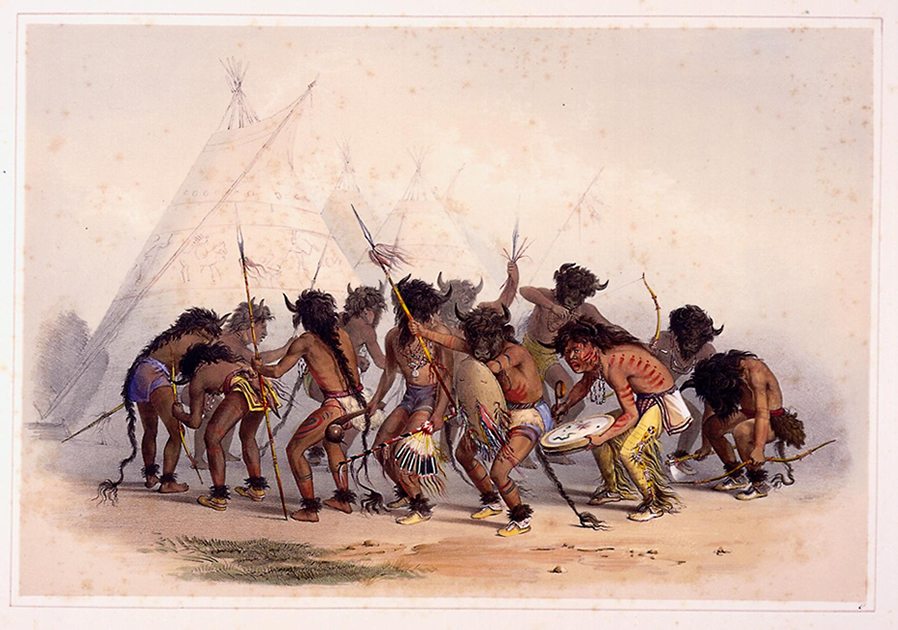

American artist George Catlin visited the Mandan near Fort Clark in 1833; drawing and painting portraits and scenes of Mandan life. His skill at portrayal so impressed MatóTópe, that he invited Catlin as the first Euro-American to be allowed to watch the Okipa ceremony, an intricate series of rites linking all of creation to seasonal conditions. As part of the earth-renewal practices, the Okipa emphasized the renewal of game animals in the Buffalo Dance ceremonies (see the George Catlin drawing).

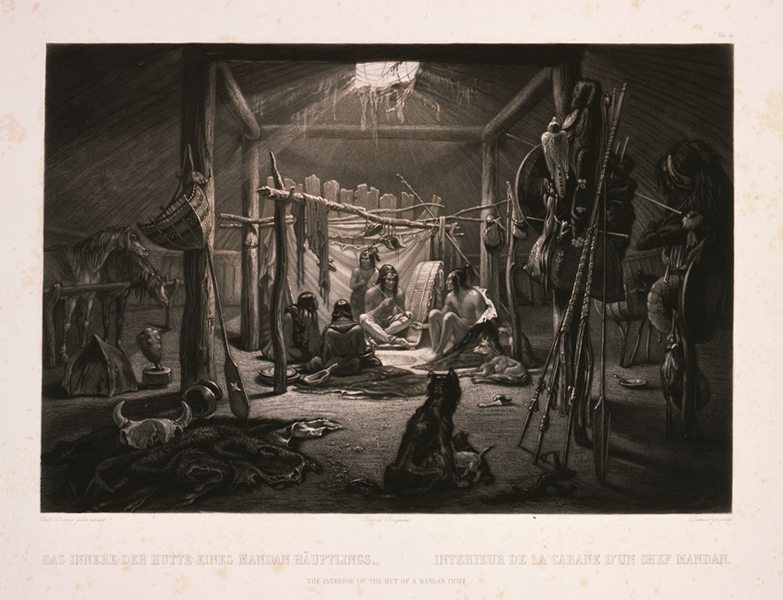

The winter months of 1833 and 1834 brought Prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied and the Swiss artist Karl Bodmer to stay with the Mandan. Bodmer made many beautiful, extraordinarily detailed sketches and paintings of the cultures, dress and appearance of the Mandan and other tribes, which are still used today as references for scholars. Bodmer and Catlin documented the Upper Missouri River cultures in their peak, just before they were devastated by disease.

In June 1837, an American Fur Company steamboat traveled westward up the Missouri River from St. Louis. Its passengers and traders aboard infected the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara tribes. There were approximately 1,600 Mandan living in the two villages at that time. The disease effectively destroyed the Mandan settlements. The thirteen clans were reduced to two divisions. Almost all the tribal members, including MatóTópe, died. Estimates of the number of survivors vary from only 27 individuals to up to 150, though most sources usually give the number at 125. The survivors banded together with the nearby Hidatsa in 1845 and created Like-a-Fishhook Village.

By the second half of the nineteenth century, the holdings of the Three Affiliated Tribes (Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara) gradually decreased. Going from 12 million acres in 1851 under the Fort Laramie Treaty to 8 million acres as the Fort Berthold Reservation in 1870. By 1910 it was down to 900,000 acres.

In 1951, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began construction of Garrison Dam on the Missouri River. This dam created Lake Sakakawea, which flooded portions of the Fort Berthold Reservation including the villages of Fort Berthold and Elbowoods as well as a number of other villages. The former residents of these villages were moved and New Town was established.

While a new town was constructed for the displaced tribal members, much damage was done to the social and economic foundations of the reservation. The flooding claimed approximately one quarter of the reservations land. This land contained some of the most fertile agricultural land upon which the agricultural economy had been constructed. In addition, the flooding claimed the sites of historic villages and archaeological sites.

Today they are united in the Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation, North Dakota, and about half of the Mandan still reside in the area of the reservation. The heart of the Mandan community is Twin Buttes. Around 6,300 people live on the Fort Berthold Reservation, and there are over 12,000 enrolled members of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation today.

The voluminous young golden eagle plumage and split buffalo horns on this bonnet signified the wearer’s status as a great warrior and leader. He had to earn the right to wear it through demonstrated bravery, as did MatóTópe (Four Bears) shown in this portrait by Karl Bodmer. The owner belonged to the Dog Soldier’s society, a group within the Mandan tribe whose major task was to police the hunt.

Listen well what I have to say… Think of your wives, children, brothers, sisters, friends…are all dead or dying…caused by those dogs the whites. Think of all that my friends, and rise all together and not leave one of them alive. –MatóTópe, Numakiki (Mandan), on the day he died of smallpox in 1837. Hymns in the Dakota Language

In this aquatint engraving, the Swiss artist Karl Bodmer, who accompanied Prince Maximilian du Wied on a North American expedition up the Missouri river in the early 1830s, illustrates one of the only known historic views of the interior of a Mandan earth lodge.