Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2003

Log Cabin Dreams: Domesticity, Women and Museums in the Early Twentieth Century

By Juti A. Winchester, PhD

Former Ernest J. Goppert Curator of the Buffalo Bill Museum and Western American History

Today’s Buffalo Bill [Center of the West] surprises many first-time Cody visitors. A complex consisting of five large modern museums presenting a vision of the West through its historical, artistic, and ethnological collections is the last thing someone would expect to find in a small, wind-swept town at the edge of the Big Horn Basin. Even more surprising is that the Center owes its beginnings to a single mother who had the vision, the energy, and the priceless social connections to get it started. While the Center is unique among institutions worldwide, we must look to its origin as a historic house museum to understand how the Center fits into women’s history, the history a American museum-building, and history in general.

Women have traditionally been regarded as the preservers of culture. An old adage reminds us that “the hand that rocks the cradle rules the world,” and history, from ancient to modern, is full of examples of women with no legal standing in their world making an impact on society by exerting their influence on husbands and sons. When the founding fathers considered what kind of government to set up in the infant United States, Abigail Adams gently reminded her husband to “remember the ladies,” hoping that her sex could gain the vote, or at least some kind of legal status in the new republic. Women’s hoped-for rights did not materialize, but an amused John Adams acknowledged women’s hidden but very real power in his answer: “…in Practice, you know, We are the subjects. We have only the Name of Masters…”[1] Later, the idea of “republican motherhood” underscored the duty of women to become literate, because it was they who would pass on new American ideals of good citizenship to their children. Meanwhile, Native American parents, but especially Indian women, struggled to preserve and pass on to their children their language and traditions in the face of unbelievable pressure to assimilate and to forget their life-ways. Recognizing women as the bearers of culture, the assimilationist reformers sought to break Indians’ links with the old way by taking children out of their homes, and placing them in boarding schools.

In the West, frontier schoolteachers formed the vanguard of expanding American cultural influence. While art and literature suggest that the American West was a nearly exclusively male domain, in reality these schoolteachers, so much a part of the westward movement, were almost invariably young, single, and female. Like westering men, young women found adventure and a way to make a living for themselves in the new territories, sometimes at the head of classes full of students nearly their own age. There were not many “acceptable” occupations open to single women on the frontier, and with few exceptions they gave up their positions if they married, as housekeeping and family obligations were considered the first duty of women. Single women serving as schoolteachers helped bring a kind of civilization to the West.

Social class, disposable wealth and societal change comprised the factors that made it possible for women to make concrete contributions to cultural preservation in the United States in the early twentieth century. Women have always worked, and this is especially true of women of the lower classes; thus cultural institutions have not traditionally been the province of women in any but the middle and upper classes. Suffrage and other esoteric interests became the business of women with the money and the leisure time to pursue occupations other than providing for their families; and some even envisioned themselves as cultural bearers for the nation, and not just their immediate kin. In the second half of the nineteenth century, the passage of property rights laws allowed women to legally keep the fruits of their own labors or goods they inherited instead of surrendering it all to their husbands. At the same time, Andrew Carnegie publicly espoused the “Gospel of Wealth,” which stated that the wealthy bore a certain responsibility to use their money for the benefit of mankind. Not believing in simple charity but engaged with the idea of helping people to help themselves, Carnegie devoted incredible sums of money to establishing libraries, museums, and universities. Women’s voluntary organizations, such as local branches of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, devoted themselves to establishing and running libraries, and with “the Star-Spangled Scotsman’s” aid, “Carnegie Libraries” sprang up in communities all over the United States. But though women were taking a more active role in the advancement of American culture, surprisingly, men rather than women remained firmly in control of the nation’s museums. Boards of trustees, administrators and curators were all educated, powerful, and wealthy men.

Women’s contributions to the museum world began slowly and under the guise of the separate domestic sphere deemed so appropriate for females. Again, as women gained wealth of their own through changes in property laws, they began to invest in art. In the late nineteenth century, however, most of even the wealthiest women confined their collections to “distaff arts” such as textiles, lace, embroidery, and domestic items rather than fine art. As collections accumulated in museum vaults, male curators had no interest in interpreting or displaying them and gladly left their care and arrangement to women volunteers. In time, female professional curators were hired to manage textile collections held by major museums in the East. Later, individuals such as Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney helped open the field of fine art collecting to women by simply flouting convention and acquiring pieces she found interesting, by financing young and struggling artists, and by supporting fine art museums, even founding one of her own.

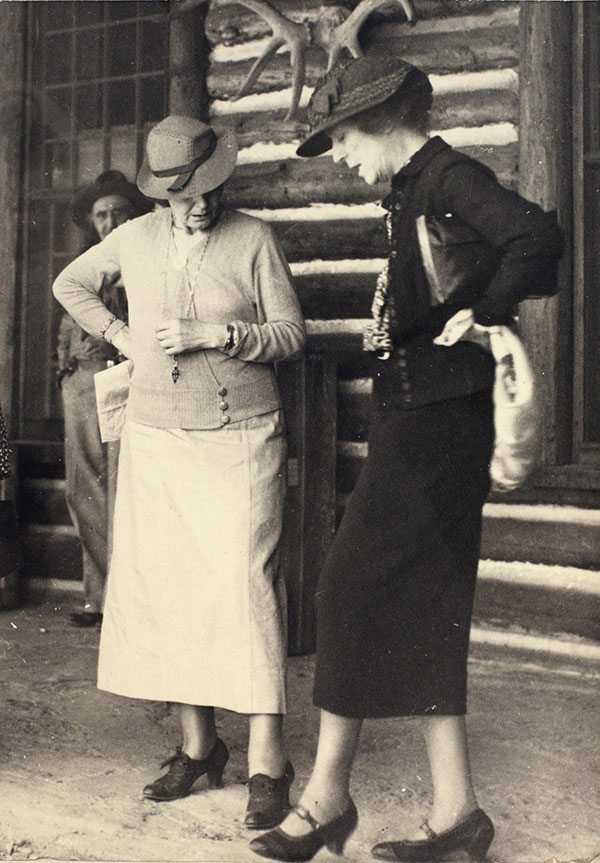

Historic house museums proved to be another outlet for women to express their cultural interest. Ladies who might not otherwise become involved in the museum establishment could become comfortable with and even enthusiastic about house museums, for what sector of society would better know how to represent a domestic space than those who occupied and ran them? In the early 1920s, the Women’s Roosevelt Memorial Association set out to reconstruct Theodore Roosevelt’s birthplace in New York City and began a national campaign to raise funds to purchase the property, erect the building, and furnish it with appropriate furniture. Among the women moving and shaking this project was the journalist Mary Jester Allen. A New York resident, divorced with one child, and niece of William F. Cody, Mrs. Allen desired to memorialize her famous uncle in some way and the Theodore Roosevelt Birthplace effort inspired her. With the help of other members of the Cody family and residents of Cody, Wyoming, she developed her idea of founding a historic house museum resembling Buffalo Bill’s TE Ranch and filling it with memorabilia and art demonstrating not only his remarkable life but the whole experience of the westward movement. Moreover, domestic space and the education of the young were still women’s provinces, even if the establishment in question was a house meant to be a museum. The Buffalo Bill Museum would send all the “right” messages.

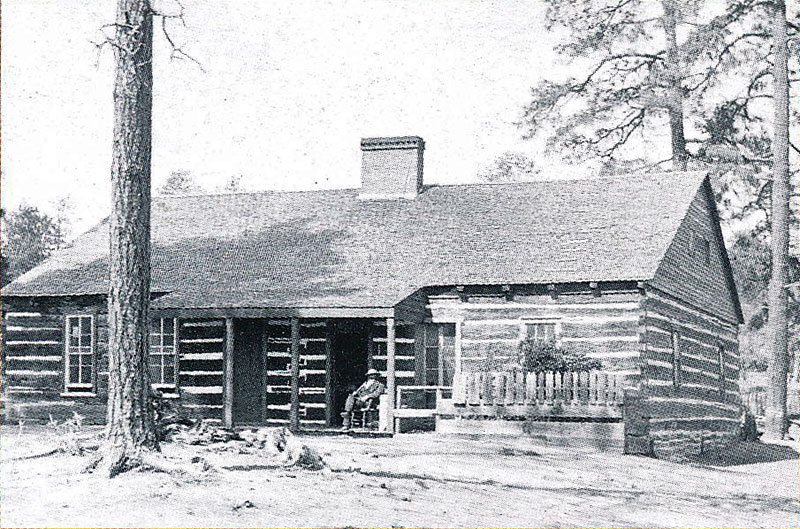

Mrs. Allen’s choice of a log cabin to represent Buffalo Bill’s legacy was not accidental. Log cabins had long held the nation’s imagination, and the humble dwelling had become an icon of American progress and self-reliance, two ideas that William F. Cody symbolized for many. A log cabin set in a comparatively modern location such as the town of Cody in the 1920s would underscore the message of Buffalo Bill’s contribution in the taming of the frontier, in bringing order from chaos. Mrs. Allen claimed that in her last visit with her uncle, he had suggested to her the idea of turning the TE into a ranch museum. This is unlikely, given the remote location of the property. Nevertheless, a log structure was erected in Cody that was supposed to be a copy of the original ranch house. Photographs of both structures show that the Buffalo Bill Museum building is not a replication as much as it is an idealized construction of the place that Mrs. Allen would have had Cody call home. The museum opened to the public on July 4, 1927.

Mary Jester Allen had big plans for the memorial to her uncle. Influenced by the burgeoning western art world, she attempted to found an art colony on the museum grounds so that artists could paint landscapes based on actual western scenes, and she laid plans for a geological museum. She used her connections in the East to stir up interest in the tiny institution, and she found a receptive audience for her ideas and ambitions. She grabbed any celebrity traveling through the area for publicity, including President Calvin Coolidge, who ended up dedicating one of the museum’s doors. Mrs. Allen and her supporters solicited collections for the museum, and she ran it herself, living in a small apartment in the building. She remained in control of the Buffalo Bill Museum until shortly before her death in August 1960.

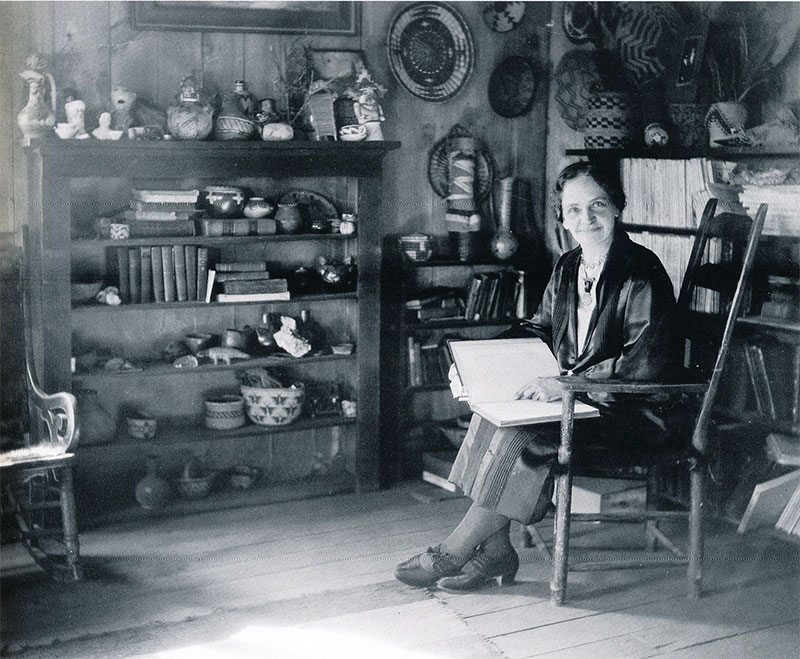

At least one other woman founded a pioneer museum in a log cabin. A veteran of the frontier herself, Sharlot M. Hall was a poet and the first woman to hold territorial office in Arizona. Miss Hall emigrated from Kansas to Prescott, Arizona, as a child in 1881 and had the opportunity to hear the stories of old-timers in the region. Among the people she met was Henry Fleury, who had accompanied the governor’s party to the territory in 1863. Fleury had known all of the early pioneers, and as personal secretary to the first governor, he had helped build the cabin that served as residence and meeting place for the territorial legislature that still stood in downtown Prescott.

No one is sure what influenced Sharlot Hall to single-mindedly pursue the preservation of the old log mansion, but she did travel to Washington, C.C. and New York City in 1925 for the inauguration of Calvin Coolidge, and perhaps there she observed the efforts of the Women’s Roosevelt Memorial Association. As territorial historian earlier in the century, Miss Hall had collected oral histories and memorabilia belonging to the pioneers who had come to the Southwest, and now she wanted to preserve this precious resource and present it to the public. She gained a lease for life from the city of Prescott and, inspired by Fleury’s tales of early Arizona, set about restoring the historic Governor’s Mansion to its earlier appearance. She filled it with her life’s collections and opened it to the public on June 28, 1928. Like Mary Jester Allen, Sharlot Hall pursued collections and used her political influence to establish and expand her small monument to the pioneer experience, and like Mrs. Allen, Miss Hall remained single and lived in a small apartment on the premises until her death in 1948.

Two museums, each memorializing the pioneer experience, opening within a year of each other, each founded by a single woman in a log cabin—could this really be a coincidence? We will never know for sure, because correspondence between the two women has not been found, if it ever existed at all. However, both Sharlot Hall and Mary Jester Allen were professional writers, and they moved in some of the same social circles. They were both most active in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Each woman had a passion for history and for educating future generations about what they had seen themselves. Both also recognized the necessity of drawing the attention of the well heeled to their institutions. As for the museums, both are products of the times in which they were founded, and both reflect the changing nature of women’s roles in the preservation of American history and culture.

Around the nation, there are other examples of historic house museums established at roughly the same time and operated by women. Historic house museums, whether in a log cabin or in a traditional home, are not only monuments to the subjects they memorialize but also testaments to the changing status and opportunity for the traditional preservers of American culture. The West is richer for them.

1. The Adams’ letters are quoted in Mary Beth Norton and Ruth M. Alexander, eds., Major Problems in American Women’s History (Lexington, Mass.: D.C. Heath and Company, 1996) p. 77.

Suggested Reading:

Kathleen D. McCarthy, Women’s Culture: American Philanthropy and Art, 1830 – 1930 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991).

Richard A. Bartlett, From Cody to the World: The First Seventy-Five Years of the Buffalo Bill Memorial Association (Cody: The Buffalo Bill Historical Center, 1992).

Margaret F. Maxwell, A Passion for Freedom: The Life of Sharlot Hall (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 1982).

Post 062