Three Women Who Preserved Buffalo Bill’s Legacy – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2017

Three Women Who Preserved Buffalo Bill’s Legacy

By Peter H. Hassrick

Curator Emeritus & Senior Scholar

In 2017, the Buffalo Bill Center of the West celebrated its Centennial year. Throughout the year, Points West shared many stories of notables—individuals who were instrumental to the Center’s success within the last one hundred years. Here, Peter Hassrick, the Center’s Director Emeritus and Senior Scholar, shares observations about three extraordinary women in particular

In 1992, on the occasion of the Buffalo Bill Memorial Association’s 75th anniversary, the museum issued a book titled From Cody to the World authored by eminent western historian Richard A. Bartlett. Even [in 2017], at the Center’s Centennial, its chapters provide a compelling account of visions, aspirations, and accomplishments that have reached well beyond local, regional, and national expectations. Bartlett highlighted hundreds of devoted individuals and groups who helped shape the incredible story of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, from U.S. presidents and senators to extraordinary and ordinary townspeople of Cody.

But of those countless contributors, three women stand out as inordinately significant: William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody’s niece Mary Jester Allen who became the founding director of the Buffalo Bill Museum; philanthropist and sculptor Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney who added art and wherewithal to the equation; and newspaper woman and gracious visionary Peg Coe who with brilliance and savoir faire led the museum’s board for more than two decades.

Buffalo Bill died in 1917. Some years earlier, seated on the porch of his famous TE Ranch west of the town that bears his name, he reflected on the way he might like to be remembered. Cody, among his many talents, was a committed educator. His Wild West extravaganzas were referred to as expositions rather than shows, and he truly felt they provided learning experiences for audiences from around the world. By 1916 his touring career had come to a close, but his dream of using experiential learning to foster an enduring understanding of western life in its multiple forms enabled him to think big that day.

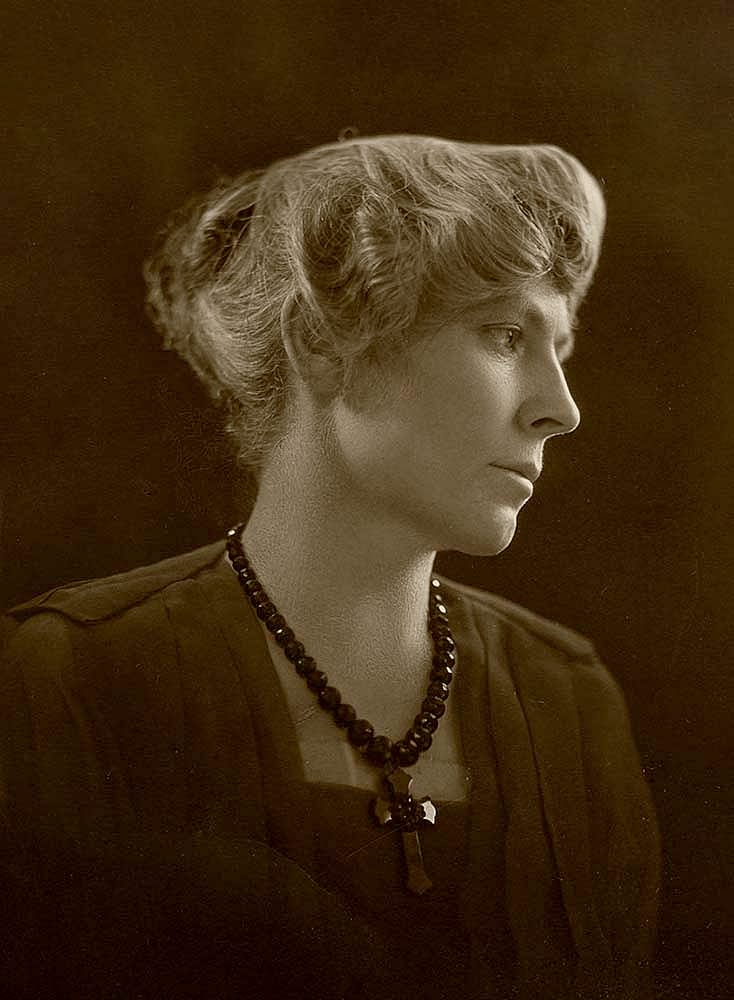

Mary Jester Allen (1875–1960)

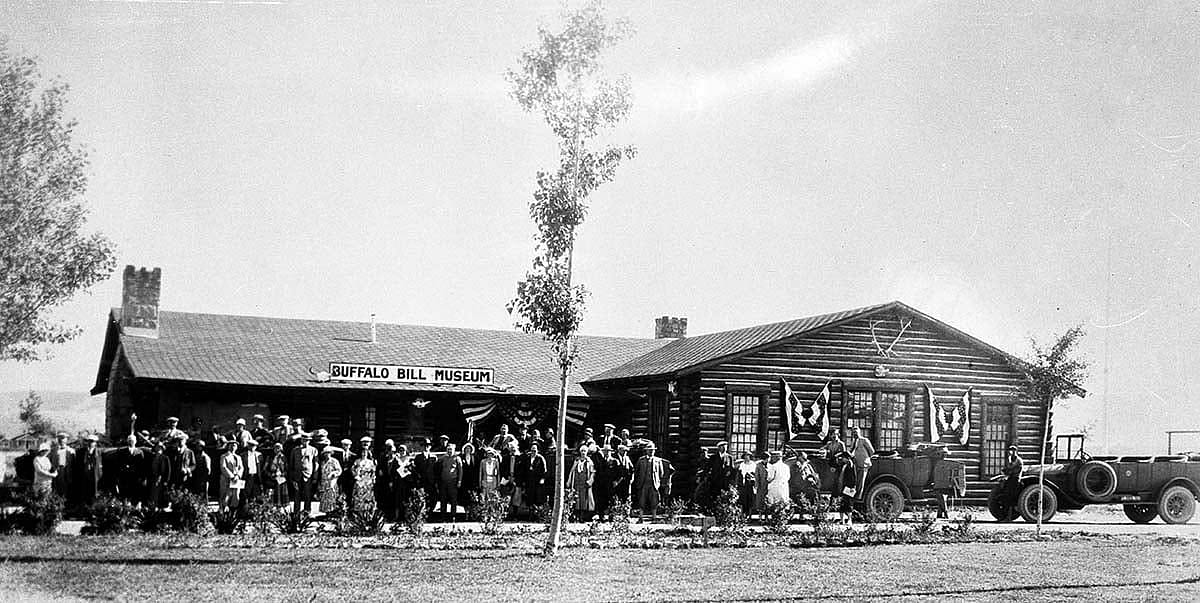

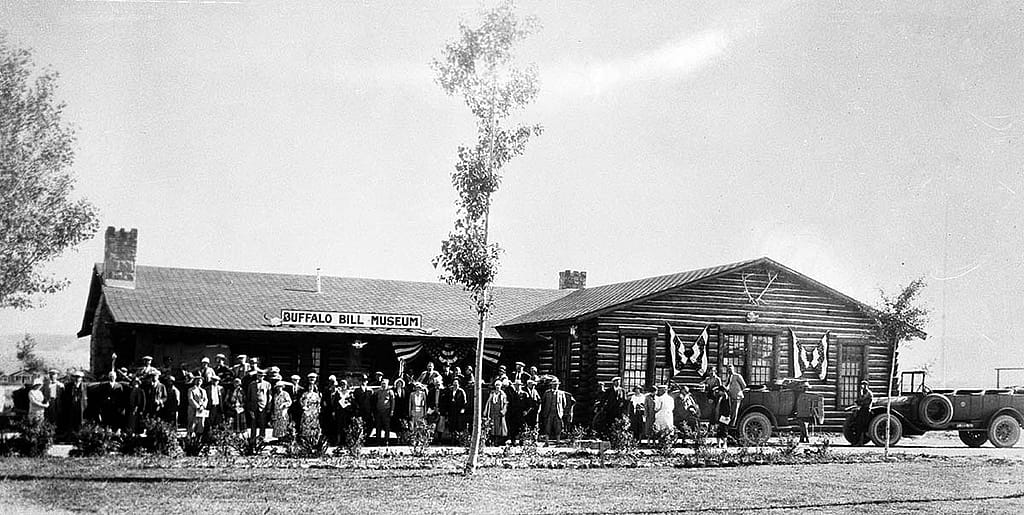

On Colonel Cody’s conceptual horizon appeared what he called a “home-ranch museum” that would include, for example, opportunities for showing “people how the western pioneer lived and worked.” At the same time he looked back into history, Cody pledged to consider the future. He hoped such a facility would succeed, for example, by “teaching the youth by seeing history.” Mary Jester Allen (Fig. 1) recounted this story time and again, employing it as the genesis narrative behind her early efforts to establish a museum in her uncle’s name. Determined to keep Cody’s chronicle alive in the town of his founding, she helped orchestrate a $5,000 memorial appropriation from the State of Wyoming in 1917 into a brand new $22,000 log structure that proudly opened its doors in 1927 as the Buffalo Bill Museum (Fig. 2). No matter that much of the money was borrowed, a start was made, a dream realized, and, as the Cody Enterprise announced, the initiative was duly sanctified, the site being claimed “consecrated as Western and sacred.”

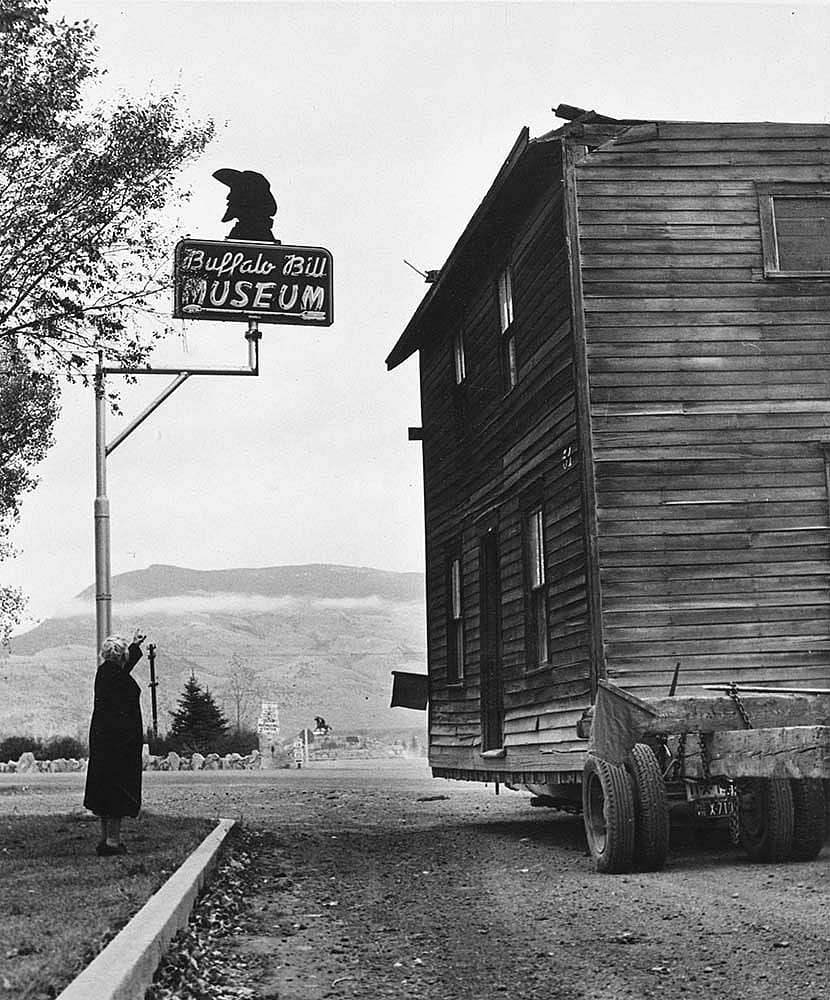

In 1960, after nearly forty years of primary involvement, Mary Jester Allen visited the museum for the last time. Through those ensuing decades, she guided the museum, watched it grow into a multi-structured facility, shepherded it through a depression and two world wars, and helped enrich its holdings. Along with the dazzling legal acumen of the board’s chairman, Ernest J. Goppert, Sr., she helped return the museum to a private venture after it had been relinquished to the City of Cody during the war years of the 1940s. She oversaw the acquisition and transport of Buffalo Bill’s boyhood home from Le Claire, Iowa, to Cody in 1933 (Fig. 3). And she was, to her dying day, a stalwart defender of William F. Cody and his dream for the future promise of history through museums. Thanks to Mary Jester Allen, the Buffalo Bill Center of the West was born, nurtured, and started on its way to what would become the formidable institution it is today.

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney (1875–1942)

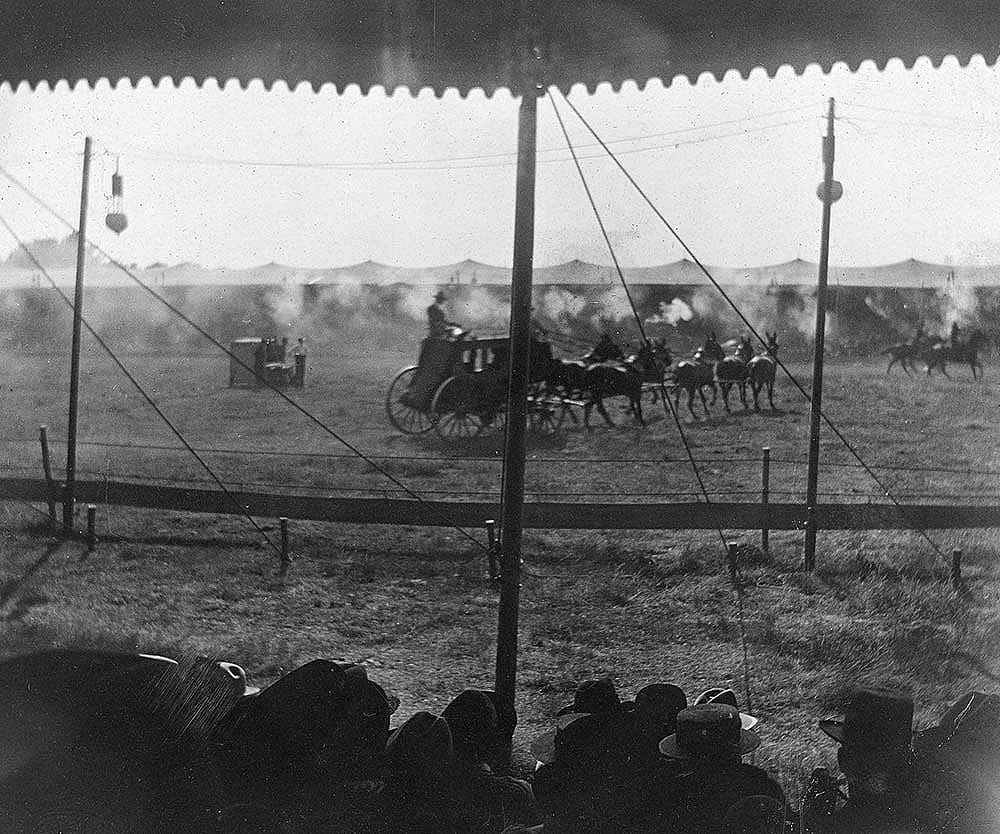

About a decade before Cody died, he featured his Wild West in New York City at Madison Square Garden. The year was 1909 and in the audience one night, in a VIP booth, was the socialite and artist Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney (Fig. 4). She brought two of her children to experience the event—her daughter Flora and her 10-year-old son Cornelius. To their collective amazement, Buffalo Bill had a life-changing experience in store for them. The second act on most Wild West programs was the Deadwood Stage (Fig. 5). Following Cody’s traditional welcome, the stagecoach rumbled into the arena, circling it once. On the second round, Indians attacked it, and then on the third, a group of cowboys rode out to “save” the coach.

On the night the Whitney family attended the performance, the coach driver stopped in front of the Whitney booth and hollered over to Mrs. Whitney, “Would young Mr. Whitney like to ride in the coach this evening?” Of course, he would! He leapt over the barriers and climbed into the historic coach. From there he was swished around the arena, attacked by the Indians, rescued by the cowboys, and then dropped, emotionally spent, back in Mama’s lap. “What a thrill!” he later wrote. He would never forget it.

Years would pass until the time, 1917, when Mary Jester Allen needed something special to commemorate Buffalo Bill’s place in Wyoming—in Cody to be specific. That year, she and the board of the nascent Buffalo Bill Memorial Association initiated the idea that a commemorative, heroic-sized statue of the Colonel would be in order. One of the board members—probably popular dude ranch impresario Larry Larom—suggested Mrs. Whitney. She was internationally renowned as a sculptor of monumental bronzes; she was devotedly American in her persuasions; and she held a special place in her heart for Buffalo Bill, in part at least because of his courtesy to her son.

After much hemming and hawing, Mrs. Allen worked up sufficient courage to knock on the artist’s door to ask if she might consider the commission. Allen had $5,000 to offer and the dream of playing a significant role in perpetuating Buffalo Bill’s legacy. It wasn’t long after she was admitted to Whitney’s studio that Allen realized that she “wasn’t selling Mrs. Whitney Wyoming, the Wild West, Cody, or the Colonel. She was selling me.” The commission was granted (Fig. 6): Mrs. Whitney would take the job, pay all the bills, and leave Allen with a lifted heart and a purse still full of cash.

Cornelius and his mother took a trip to Yellowstone National Park in 1922. From the geysers, they drove east to Cody. “It was there,” wrote Cornelius later, “that we met Buffalo Bill’s niece, Mary Jester Allen.” The two women were “very simpatico” as they searched for the proper site for Whitney’s sculpture, The Scout, that was taking shape back in New York. Not only did they find a location, but, Cornelius recalled, “my mother purchased forty acres of land” for the Association on which “to create a museum complex of western art” someday. When The Scout was dedicated on July 4, 1924, it was silhouetted against Rattlesnake Mountain to the north (Fig. 7) and looked back over the land on which the future Whitney Western Art Museum would eventually be built.

Mrs. Whitney passed away in 1942. Her final wishes for her children were that Flora would take over stewardship of the burgeoning Whitney Museum of American Art her mother had launched in New York a decade earlier. As for Cornelius, Mrs. Whitney beseeched him that he might support that Cody “museum complex of western art” at some point should the trustees ever commit to collecting art in a serious way.

Following the Second World War, probably in the late 1940s, Cornelius received an invitation from Mrs. Allen to visit Cody again, attend a summer rodeo, and meet some of the Buffalo Bill Museum’s board members. He responded in the affirmative and was totally enthralled by the warm welcome that was lavished on him. He met the board chairman, Ernest J. Goppert, Sr.; Buffalo Bill’s grandson, Freddy Garlow; and the museum’s future chairman, Peg Coe (Fig. 8). They spoke of Mrs. Whitney’s dream, but it was pie-in-the-sky because the museum, at that point, had very little art—not much more than a few portraits of the Colonel. That simply would not have satisfied Mrs. Whitney’s requirements.

Margaret “Peg” Coe (1917–2006)

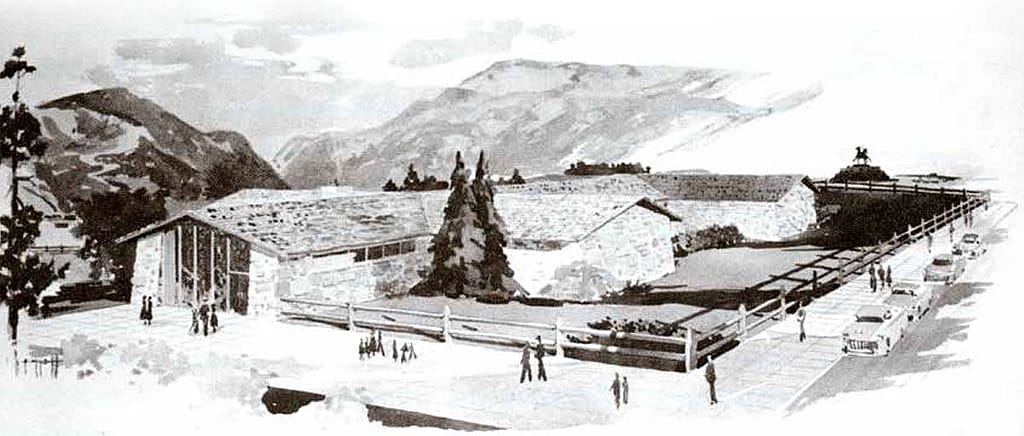

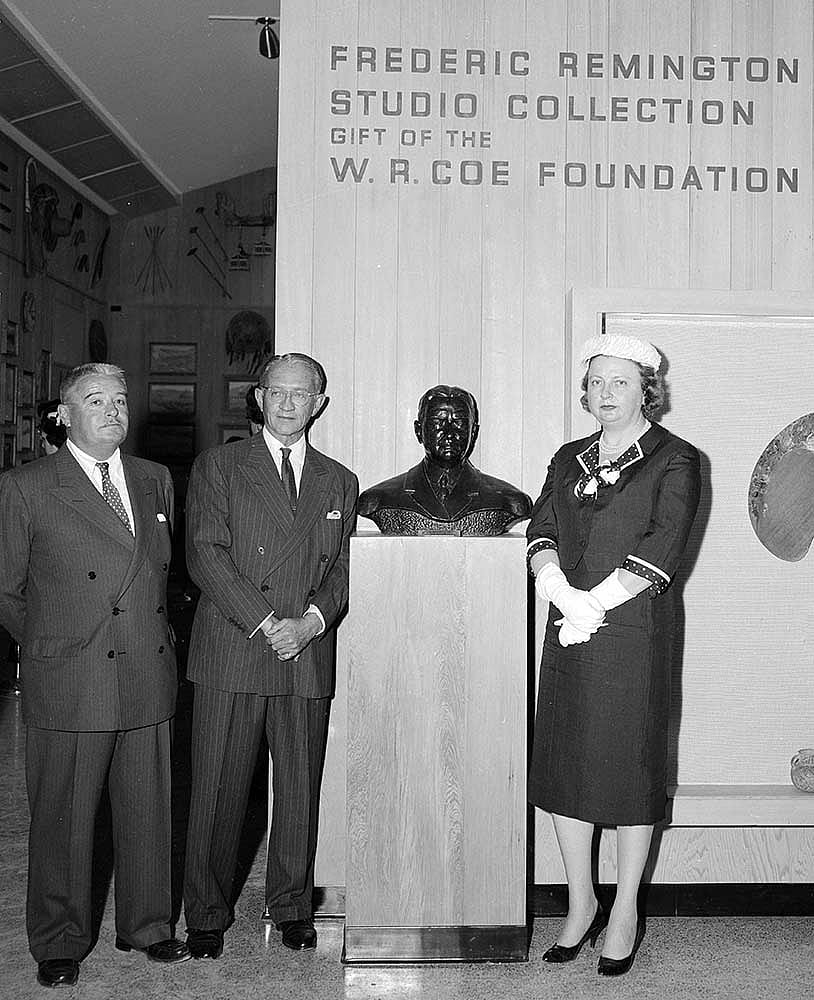

Then, about a decade later, the Coe family stepped forward to further the cause. The family patriarch, W.R. Coe, had passed away in 1955 and left a sizable trust that became the Coe Foundation. His children managed that foundation, and two of them were connected to the Buffalo Bill Museum—Henry H.R. Coe as a trustee, and the Honorable Robert Coe as an avid supporter. About 1957, the Coe Foundation purchased a remarkable group of art and artifacts, the Frederic Remington Studio Collection. Then, the foundation gave it to the Buffalo Bill Memorial Association, and that gift became the leverage that persuaded Cornelius to fund a new museum for art of the American West in his mother’s name. Thus, in 1959, the Whitney Gallery of Western Art (today’s Whitney Western Art Museum) was born (Fig. 9).

Cornelius attended the opening of the new gallery and was so impressed with the extraordinary installation of works the new director, Harold McCracken, had assembled (most on loan from the New York art dealer M. Knoedler & Co.) that Cornelius offered to double his initial construction gift of $250,000 so that the museum might purchase some of the best works. Therefore, the collection of art had increased severalfold overnight (Fig. 10).

When Henry H.R. Coe died in 1966, his widow, Margaret “Peg” Coe, took his place on the Association’s Board of Trustees.

Before that, her mother, Effie Shaw, had been a longtime board member as well. Within ten years, in 1976, given her personal charisma, social poise, managerial savvy, and clarity of vision, Peg was elected chairman, a role she would hold for the next twenty-three years before stepping down in 1999.

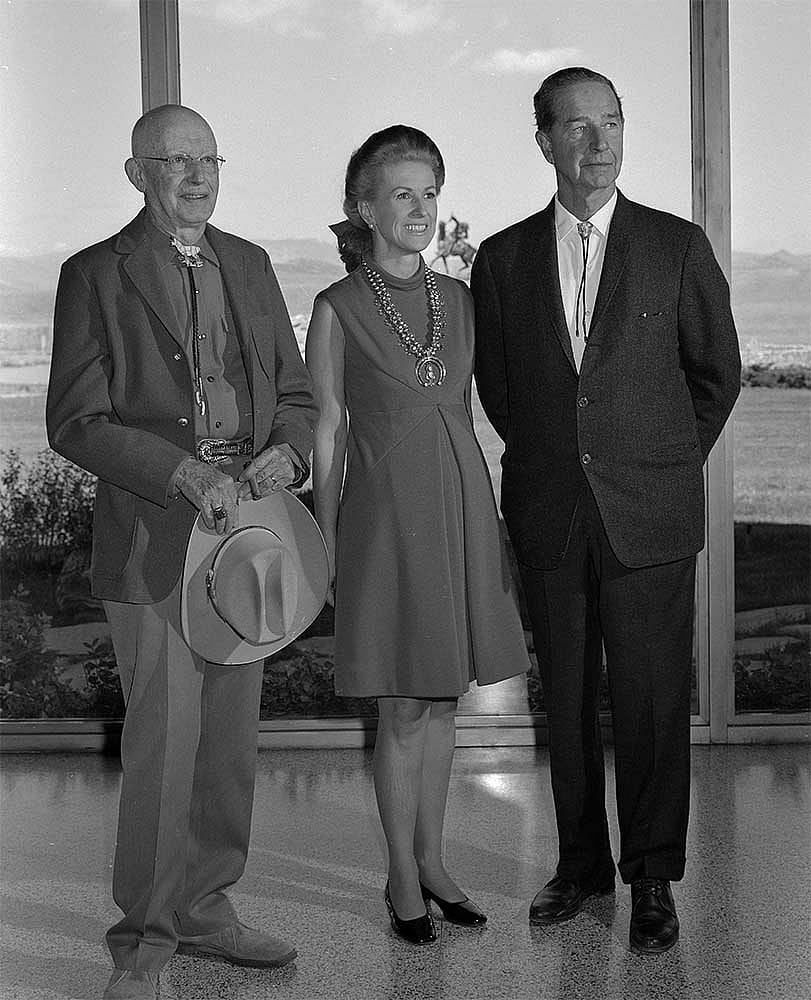

Cornelius had been charmed by Peg early on, and he, too, became a trustee. Together the benefactor and the chairman worked closely to further not only Mrs. Whitney’s wishes through many enhancements and collection additions to the Whitney, but to spearhead the substantial growth of the larger institution, what was then called the Buffalo Bill Historical Center.

Under Peg’s aegis, the facility doubled in size to add the Plains Indian Museum, the Cody Firearms Museum, and the McCracken Research Library. She boldly advocated for the inclusion of Northern Plains tribal representatives as advisors in the conception and perpetuation of the Plains Indian Museum (Fig. 11). She also insisted on professionalism within the museum, and pushed successfully to have the institution officially accredited by the American Association of Museums (now the American Alliance of Museums), and formally aligned with the Association of Art Museum Directors. Like Mrs. Whitney before her, Peg was a lover of art and encouraged the museum’s staff to pursue major art exhibitions and scholarship throughout her tenure as chairman.

Furthering the Whitney family’s philanthropy, Peg used her considerable persuasive powers to build the museum’s physical plant and its endowments. The first endowment had come from the Coe Foundation, a gift of approximately a half million dollars. Following the counsel of fellow board member William E. Weiss, Peg championed what was then known as the “60/40 rule.” Any new construction would require that from every dollar raised, 60 percent would go toward the construction and 40 percent to endowment. By the time of her retirement as chairman, the Center’s endowment had grown to more than $30 million.

Three remarkable women—Mary Jester Allen, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, and Peg Coe—took the story of one of the nation’s most masculine, heroic figures and designed plans to create an ever-growing, ever-improving museum complex with complementary programs based on his dream of teaching America about the historic West. As much as—and in most cases more than—any of the myriad players in the museum’s one-hundred-year narrative, this trio is to be credited with preserving and perpetuating William F. Cody’s extraordinary legacy.

A prolific writer and speaker, Peter Hassrick has served as guest curator of numerous exhibits nationally and internationally. He is a former twenty-year Executive Director of the Center of the West and has served tenures directing the Denver Art Museum’s Petrie Institute of Western American Art, the University of Oklahoma’s Charles M. Russell Center for the Study of Art of the American West, and the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, as well as working as collections curator at the Amon Carter Museum. He is currently Director Emeritus for the Center.

Post 227

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.