The Harry Yount Enigma: Yellowstone’s First Park Ranger

Buried among the sublime passes of the Sierra Nevada are old men, who, when children, strayed away from our crowded settlements, and, gradually moving farther and farther from civilization, have in time become domiciliated among the wild beasts and wilder savages—have lived scores of years whetting their intellects in the constant struggle for self-preservation; whose only pleasurable excitement was to be found in facing danger; whose only repose was to recuperate, preparatory to participating in new and thrilling adventures. Such men, whose simple tale would pale the imaginative creations of our most popular fictionists, sink into their obscure graves unnoticed and unknown. – Bonner, T.D. 1892. Life and Adventures of James P. Beckwourth. London: T. Fisher Unwin. Page 2. “Preface to the American edition.”

In about 1873, in the month of April, Harry Yount was camped along the Platte River trapping beaver. One morning he woke up to find himself in the midst of a blinding blizzard. He and his dog holed up, in Harry’s tent, for one day, that night, and into the next. Forty hours. Harry could not get out to cook, and so the two of them lay wrapped in Harry’s blankets. During the second night it occurred to Harry that the snowfall was enough to smother and crush them, so he tried shoveling his way out the front with a board. This did not work. When the gale ceased he cut his way out the top of the tent, and found the friendly spring landscape of a few days ago covered in white. They hadn’t had anything to eat for forty hours. Harry dug his kitchen out, squatted in the snow, and lit a fire.

As I’ve written, frontiersmen who become famous usually do so because someone wrote a book about them. John Filson was a schoolteacher turned land speculator who decided to increase the value of his holdings by writing a book about Daniel Boone. “I have been but a common man,” Boone said. Maybe not, but he was not the only Kentucky frontiersman who laid his life on the line. Kit Carson became famous when John Fremont hired him as a guide and made him the hero of Report of the Exploring Expedition to the Rocky Mountains (1843). These guys were indifferent to their fame. If they hadn’t been written about, how well-known would they be?

In Harry Yount’s case, he became famous because he wrote about himself – just not very much. Judging by his actions, he was absolutely as indifferent to public acclaim as Boone and Carson, but Harry Yount ended up with a mountain and an award named after him.

Harry Yount grew up in Missouri and enlisted in the Union Army after the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. Shot in the foot in the Battle of Pea Ridge, he was captured by Confederate forces. He underwent a forced 90-mile march, barefoot, to Fort Smith. After 28 days in prison he was exchanged in a prisoner swap. Apparently this exposure caused him aches and pains for the rest of his life, but it did not stop him from reenlisting shortly thereafter, seeing action in eleven more engagements. I suppose at this point Harry could have gone back to his folks in Missouri, done the sensible thing, and taken up a farm, but he didn’t.

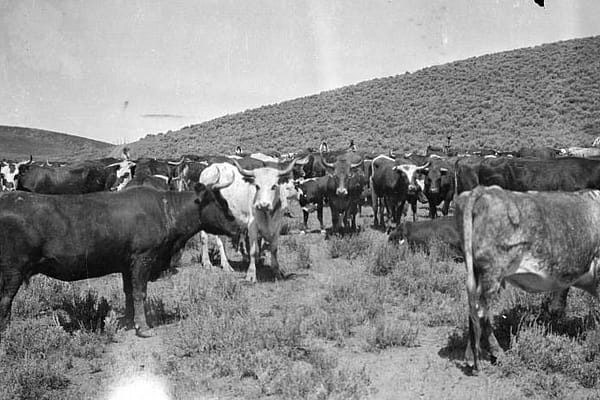

The year 1866 found Harry Yount working as a bullwhacker on the Bozeman Trail. Referred to as “the Bloody Bozeman,” the route was so hot the army tasked Jim Bridger with finding an alternate route through our own Bighorn Basin, which was abandoned after a year due to lack of water. In peripatetic frontiersman style, Yount hunted buffalo, shot “pheasants” for the Smithsonian, and worked as a market hunter. His fortunes changed, for the purposes of our story anyway, when he hired on to the Hayden Expedition.

Tasked with surveying the natural history of Yellowstone and various western states, Ferdinand V. Hayden spent years leading expeditions into the western outback. The surveys included, at times, photographer William Henry Jackson, painter Thomas Moran, and Harry Yount, who hired on as a packer. He joined Hayden in 1873, and spent at least seven summers with them in Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming. It may have been under this guise that he came to the attention of Philetus Norris, the second superintendent of Yellowstone National Park.

The first superintendent, Nathaniel Langford, had only visited the Park three times. Norris maintained a winter home in Michigan, but he actually spent part of every year in the Park during his tenure, and he advocated for roads and the protection of game. At Yellowstone’s founding in 1872, it was remote enough to be an abstract concept to the politicians who adjudicated the funds for the Park: none. The lack of context for the early overseers of Yellowstone National Park can be seen in its borders, laid out without any thought of geographic barriers or landmarks.

Yellowstone’s early years as a park were fraught with political problems. This was due to elected officials who did not realize its scope and remoteness, and the fact that the locals, such as there were, were gorging themselves on the abundant wild game. Early on, local tribespeople, who surrounded the park, went in to supplement the inadequate larder being handed out on the reservations. Later, white frontiersmen used it as a hunting and trapping ground; the concept of environmental protection was foreign to them. Norris, a whirlwind of a human being, foresaw something different. A park with roads to the sights, where eastern tourists could come and see fumaroles and bubbling geysers. The vast numbers of wildlife, bison and bears, had to be protected for public viewing. Enter Harry.

Norris managed to finagle $15,000 out of Congress for Yellowstone, and $1,000 of this went to pay Harry Yount’s salary. He was given the title of “gamekeeper,” the first and only person to ever hold that title around here, and sent on his way. Yount built a cabin at the junction of Soda Butte Creek and the Lamar River, and spent the winter alone. His nearest neighbors were in the Clark’s Fork Mines, today known as Cooke City, and at Mammoth Hot Springs, eighteen and thirty miles away, respectively. Occasionally, someone from Mammoth would show up, but Harry was basically on his own.

Try it. I once spent four days alone in a hunting camp in the Wind River Mountains. At the end I was hearing things and desperate to see any human at all, and I am not the most social person. Richard Jones is a long-time Yellowstone Park Ranger who spent several winters stationed in Lake Clark National Park, in Alaska, by himself. He told me he spent nine weeks without seeing another human being. I asked him about this, and he said it was the happiest time in his whole life.

Yount wrote two reports on his experience as gamekeeper, which were entered into the Congressional Record. Harry Yount turned out to be an erudite writer.

I do not think that any one man appointed by the honorable Secretary, and specifically designated as a gamekeeper, is what is needed or can prove effective for certain necessary purposes, but a small and reliable police force of men, employed when needed, during good behavior, and dischargeable for cause by the superintendent of the park, is what is really the most practicable way of seeing that the game is protected from wanton slaughter.

It was thirty-five years until park rangers would be employed, but with his report to Congress, Harry planted the seed.

Harry Yount worked as gamekeeper for only fourteen months. Norris did not want an old-school frontiersman to be the face of America’s first national park. He wrote to his superiors that Yount was “…a sober and trusty man I should ordinarily hire at regular wages as an excellent hunter, still he is that and nothing else, being by tastes and habits, a gameslayer and not a game preserver.” Norris, also, was dismayed by Harry’s complete disinterest in road building.

After his dismissal from the nascent Park Service, Harry went on his way. His stomping ground was the Laramie Mountains west of Wheatland, where he hunted, trapped, and picked rocks out of the ground for the next forty years. He also made a hobby of crawling into dens after bears. Yount was particularly interested in prospecting and registered many mining claims over the years. In Yount’s later years Thomas Bryant visited Harry at his home in Wheatland. Yount’s service in the military enabled him to get a pension, and he lived comfortably. Bryan wrote, “…he gave the appearance of a man who knew no fear.” In his old age Harry was particularly interested in aviation; he wanted to become a pilot.

Today, Yount’s Peak marks the headwaters of the Yellowstone River. And in 1994, the National Park Service established the Harry Yount Award, given to award “the best of the best” in the ranger profession.

Harry Yount died in Wheatland, Wyoming on May 16, 1924. A couple days before, he was seen around town. He was looking for a ride out into the hills west of Wheatland. He had heard of a gold outcrop out there and he wanted to check it out.

Written By

Eric Rossborough

Eric has been rooting around the West since he took a job at the McCracken Research Library. Eric comes here from Wisconsin, where he worked at a public library, and enjoyed working on prescribed fires and fishing for bass and bluegills. He has a lifelong interest in natural history and the Old West.