Advertising the Frontier Myth: Poster Art of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West

In 1835, P.T. Barnum bought a human being. Barnum saw an ad in the Pennsylvania Inquirer. Joice Heth, an elderly African-American, was being promoted as George Washington’s nanny, but the promoters weren’t making much money on her. Barnum paid one thousand dollars, set up “Barnum’s Grand Scientific and Musical Theater,” and took her on the road. For 50 cents, you could see the woman who took care of George Washington when he was a kid. Heth was supposedly 161 years old.

Barnum hung posters all over New York, that read: “Joice Heth is unquestionably the most astonishing and interesting curiosity in the World!” Barnum claimed to believe the story about Heth’s age, but he also wrote fake, anonymous letters to the newspapers denouncing the whole thing as a fraud. He also waved around a forged baptismal certificate. Barnum wrote, “I saw that everything depended upon getting people to think, and talk, and become curious and excited over and about the ‘rare spectacle.’ Accordingly, posters, transparencies, advertisements, newspaper paragraphs – all calculated to extort attention – were employed, regardless of expense.”

The age of public relations was underway.

I come from an advertising family. My Dad parlayed a World War II G.I. Bill scholarship into the middle class. The professional slot he chose was advertising. I never heard him discuss a desire to do or be anything else. Early on, he invented the fun slogans on the back of the Salada Tea tag as a Boston adman. By the time I came around he had established his own business, which he operated out of a bedroom in our house. His office was stacked with cassette tapes of jingles he’d written, and posters for bank ads featuring dead movie stars. I could sing some of his music, and the advertisements in TV and magazines were analyzed constantly. My older brother was a New York ad executive at this time. I liked going to visit him at his sleek apartment in New York. He flew around the world and worked on various ad campaigns for Leggs panty hose and Aquafresh toothpaste. It all seemed part of a glittering, easy world to me. When my Dad took me to baseball games at Fenway Park he would introduce me to people he knew, admen in their wool business jackets. My Dad kept on doing ads his whole life. Even into his latest years he devised ad campaigns for local businesses in exchange for free restaurant meals and gardening supplies.

I didn’t want to be an adman. I wanted to be a cowboy, and the impetus for this was in part a book held by my elementary school library, Buffalo Bill’s Life Story. I had checked it out so many times you could see my name going all the way down the card in the back of the book. I didn’t realize at the time that it had probably been written by John Burke, Buffalo Bill’s publicist, and that my father and brother’s trade were somehow tied into my own childhood interests. The gleaming world of the 1970s and the rural frontier past I was obsessed with were tied together, and had come together, decades earlier in a part of the country that was neither Far West nor Northeast Coast.

When Ned Buntline discovered Buffalo Bill sleeping under a wagon in the Nebraska heat in 1869, advertising was in its infancy. At this time, advertisements consisted of terse announcements in the letter-press printed newspapers of the time. You could find out little more than that the product existed. And there weren’t many of them. Buntline was the first guy to put Cody on stage, but the man who really made him famous was John Burke.

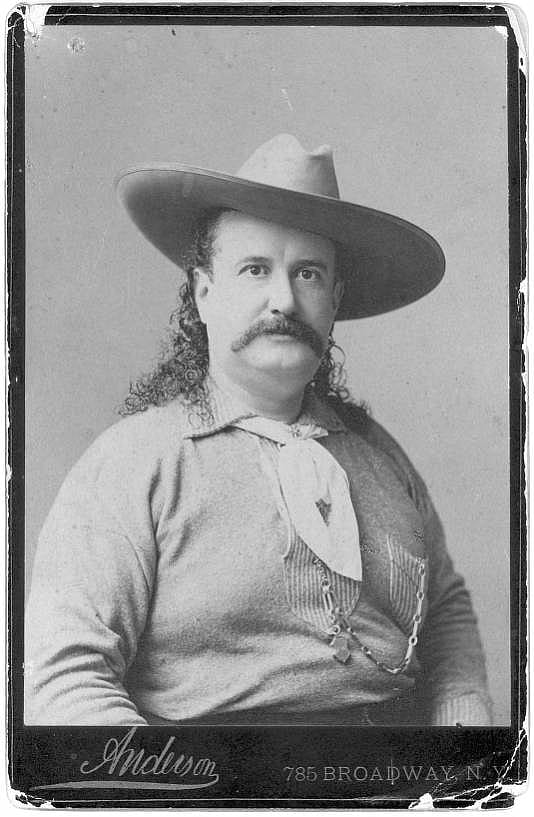

The first thing you could say about John Burke is that he believed in the product. He grew his hair long, put on a big hat, and claimed to have been at the battle of Wounded Knee. At that time he already weighed three hundred pounds. Burke did not resemble a 1960s adman. He didn’t resemble a 1980s adman either.

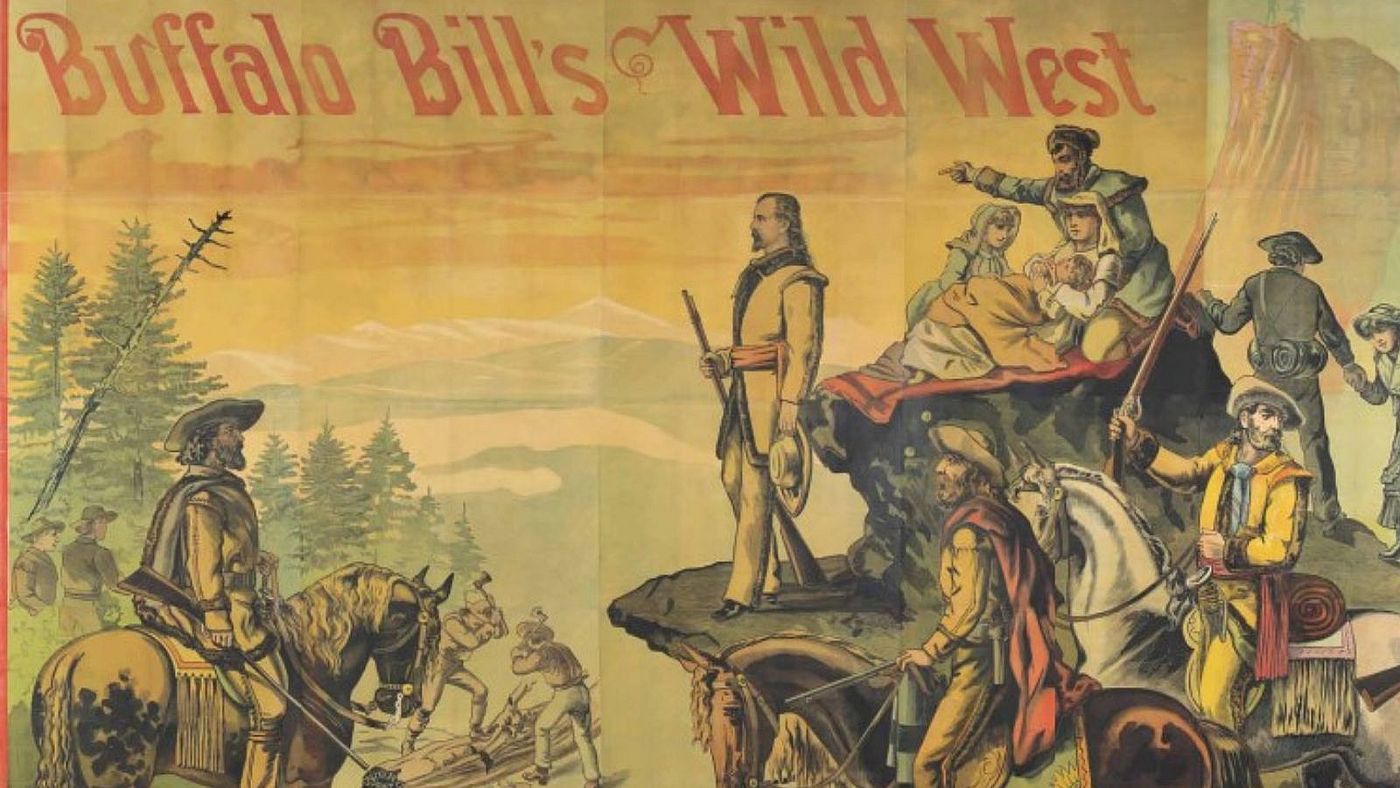

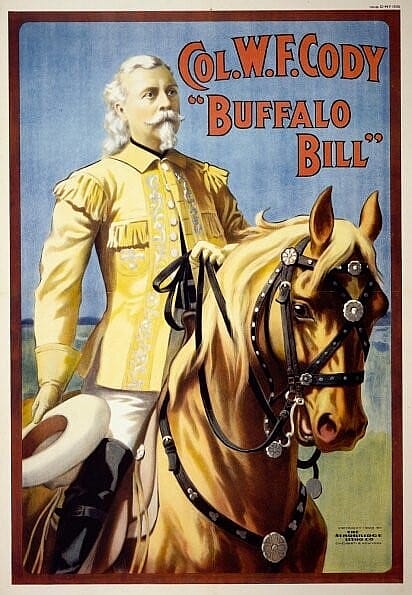

No matter. Through his force of personality and networking skills, he made Buffalo Bill Cody an international superstar. He bagged what may be the first celebrity endorsement of all time, from Mark Twain, which he turned into the world’s first press release. He cultivated newspapermen, who recognized him as one of their own. Burke brought Indians to the Eiffel Tower and to meet the Pope. He invented the mobile billboard, a horse-drawn carriage with a giant picture of Buffalo Bill on it. He wrote, in florid style, that the Wild West was “Supremely and originally great. The mirror of American manhood…. Promoted by kings, honored by nations. A paragon at home, a triumph abroad…. All time’s greatest and most famous exhibition, it towers alone, in solitary and magnetic grandeur.”

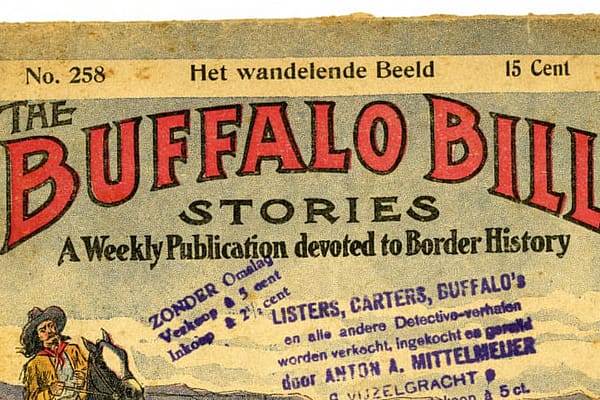

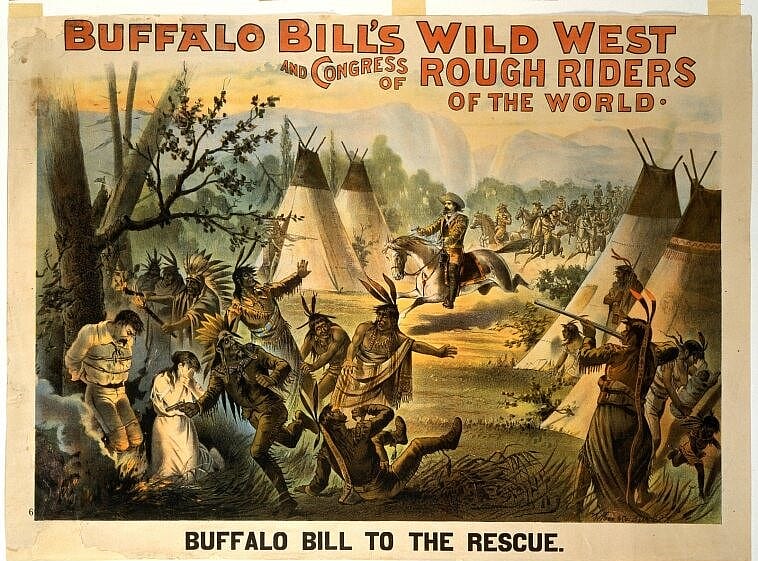

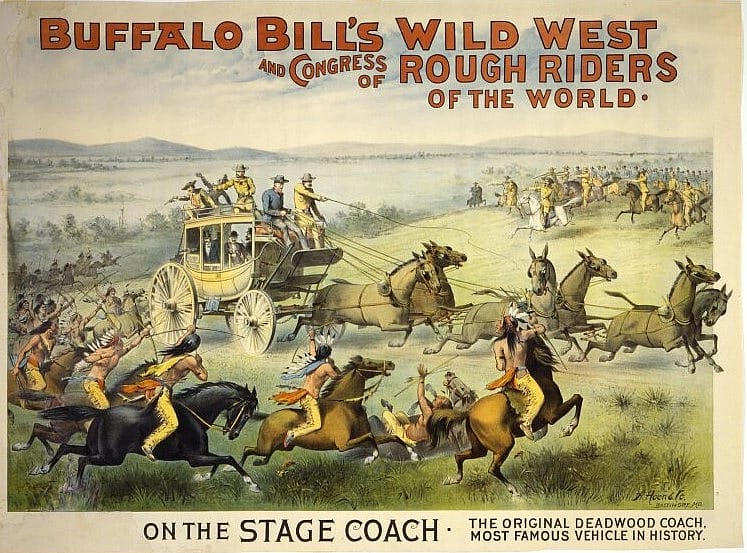

In a day before television, who’s going to miss a circus like that? Only Burke wouldn’t allow it to be called a circus. He called it, “The only object teacher history has ever had.” And to be fair, the team that assembled around Buffalo Bill Cody went way beyond what had been done in the past to promote circuses, or anything else, for that matter. And in an era before billboards or magazines with color advertisements, the way this was done was through posters.

Even if you didn’t go to the show, the posters were everywhere. Developed in the late 1790s, lithographic posters were, in a sense, art for the people. The introduction of color posters must have been a startling development; before that, posted bills had been in black and white. To walk down the street and see colored posters everywhere must have been like stepping out of a black and white world into something entirely different. And in the late 1800s, they were everywhere. Circuses used them as a matter of course, but the most sophisticated methods of production and distribution were developed by Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. Cody, Nate Salsbury, Louis E. Cooke, and John Burke, along with James Bailey of Barnum and Bailey fame (that’s right, James Bailey took up with Cody after the passing of P.T. Barnum) constituted a P.R. juggernaut that developed many of the techniques that were used in the 20th century to promote consumer products, movies, and political candidates.

Not only did Buffalo Bill’s Wild West produce more posters than other circuses, they were of higher quality. Advance teams showed up ahead of time and papered towns and barns with posters – in a two hundred mile radius around the show site. As Jack Rennert, who collected many of the posters in the exhibition Advertising the Frontier Myth: Poster Art of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, wrote, “It was Buffalo Bill’s good luck – and our good fortune as well – that the golden age of tent shows – 1880 to 1910 – coincided with the golden age of the American poster.” Advances in printing technology in the late 19th century meant better posters, and Burke and Cody believed in the personal touch, showing up at these printers’ offices, supervising the poster printing, and cultivating relationships. Using more than a dozen firms, Buffalo Bill developed many lasting friendships with these printers. One of them, George Bleistein, eventually saw fit to decamp from Buffalo, New York, and head to Wyoming, where he helped found the town that bore his patron’s name.

The marketing techniques used by these representatives of the past were right out of the future. And their fore-figure, Buffalo Bill, was the harbinger of the celebrity-based media culture that would take over the 20th century. And where that past and the future sat next to each other was at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exhibition, the Chicago World’s Fair.

Chicago beat out New York, Washington, D.C., and Saint Louis for the Fair. It sat between the East and the West, it was new, and deemed by patrician East Coasters to be crude and inadequate to the purpose of plugging the American future. In retrospect, it was perfect. Nate Salsbury, Buffalo Bill’s business manager, applied for a spot, but balked at the terms: fifty percent of the admissions gate proceeds. Cody’s team got around that by leasing a 15-acre tract of ground right next to the Fair. It must have rankled, but it was too late.

Cody and company outdrew the World’s Fair at the beginning. They performed on Sunday, while the World’s Exhibition was closed, at least to start with. The Wild West effectively outshone the wonder of the age in any number of ways. For instance, when the Fair cancelled a free children’s day because it would cost too much in ticket sales, Buffalo Bill gave a free train ticket, along with admission, along with all the ice cream and candy they could eat, to any kid who was willing to show up. 15,000 did.

The 1893 World’s Columbian Exhibition heralded the future: people saw the first motion picture, the first Ferris Wheel, the first electric light bulb, and, most magnificently, the Grand Illumination: all at once, hundreds of electric lights going on at dusk. It was the first time the public had seen outdoor public electric lighting. Architect Daniel Burnham constructed an entire city, a horde of neoclassical buildings on what a few months earlier had been a swamp. Attendees were overwhelmed.

In a very real sense, this marked the end of the wide-open, pavement-less past romanticized by Buffalo Bill. The Wild West, was, indeed, the West that had passed. Ironically, one of the Columbian Exhibition features was historian Frederick Jackson Turner giving his talk, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” which essentially declared the frontier closed — while Buffalo Bill and his Congress of Rough Riders cavorted nearby. It was one of the Buffalo Bill’s best years: they cleared a million dollars, as Wild West goers ate the first hamburgers and carbonated soft drinks that had ever been offered.

The Chicago World’s Fair was in a new city, and it inspired in people an optimism and hope for the future, for the upcoming 20th century. “There has come to pass…a new sense of unlimited human kinship and fellowship,” wrote one reporter. While the World’s Fair heralded the future, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, which squatted uninvited next door, heralded the past. And Buffalo Bill’s fever dream of the Wild West has squatted unimpeded in the minds of people ever since. Either way, both these strands of thought and entertainment were pushed and promoted by the brand-new nascent fields of advertising and public relations. And the visual element of the past part of it, at any rate, was seen in the colorful, wonderful posters which are on display through October 2024 in the Duncan Gallery.

Advertising the Frontier Myth: Poster Art of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West opened in the Center’s Anne & Charles Duncan Special Exhibition Gallery on May 18 and runs through October 24, 2024.

Written By

Eric Rossborough

Eric has been rooting around the West since he took a job at the McCracken Research Library. Eric comes here from Wisconsin, where he worked at a public library, and enjoyed working on prescribed fires and fishing for bass and bluegills. He has a lifelong interest in natural history and the Old West.