“There wasn’t any make-believe or made-up stuff:” the Western Work of James Bama

Don Schmalz was riding up Trout Creek. The year was 1973. The wind was coming straight out of the north and it was snowing. He was leading two hunters into the backcountry. He tucked his chin into the sheepskin collar of his coat, a recent gift from Bob Dohse, his employer and benefactor. Bob was letting Don live on a ranch he owned. Don rebuilt all the corrals and helped with the calves.

Don Schmalz dated his desire to become a cowboy from his youth, spent reading Zane Grey novels under the covers with a flashlight after he was supposed to have gone to bed. I had read Zane Grey as a kid also, the red, blue, and tan books. I liked them, but they were a little heavy on the romance, I thought. I liked the part about the country, but the romance was sap.

“Well, you musta been married a long time when you read those books,” Don said to me.

Don and a friend of his left North Dakota when they were eighteen. Don was looking for a place to live. They toured through Colorado and then up north. On the way down out of Yellowstone they came into the Wapiti Valley. “You can keep going if you want to,” Don told his buddy. “I’m staying here.”

Bob Dohse gave Don a job mopping floors at his inn, and then moved him up to ranch and cattle work when he found Don to be a competent farm hand. But now Don was living the dream. The wind blowing straight in his face out of the north, leading hunters into the backcountry, riding, in the open.

A man was jogging. This is not a typical sight in western Wyoming, particularly in the early seventies. The guy looked up at Don. “Sir!,” the jogger said. “Hey you up there! Hold up, hold up, please.”

“Whose land am I on now?” Don thought. There had been more people moving in, and more posted signs. To get to the hunting country Don had to ride a ways already.

The man jogged up next to Don’s horse and looked up at him. “I like the way you look,” he said.

Don looked down at him, nonplussed. “I’m a famous artist,” the man said. “And I would like to paint you.”

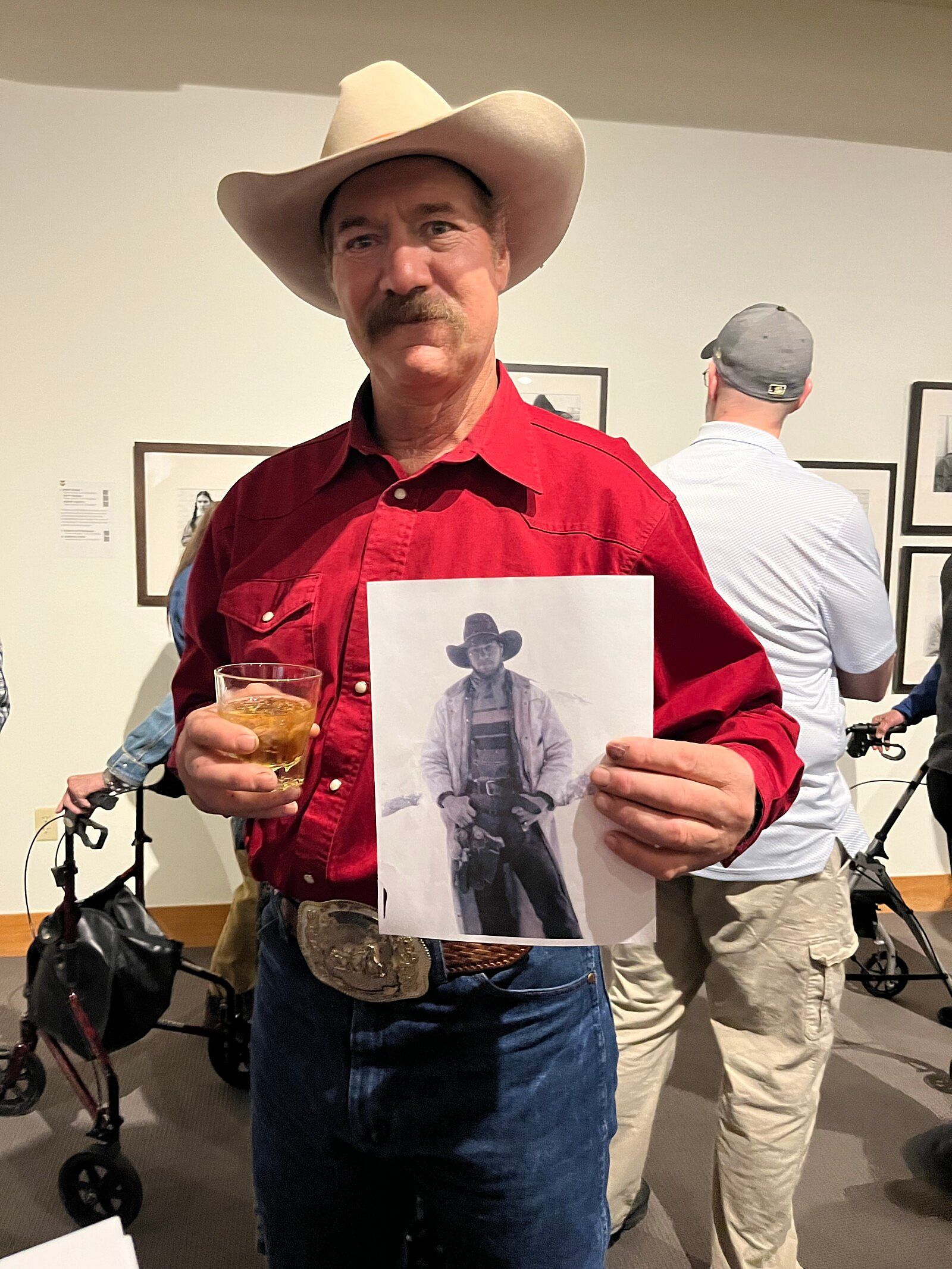

Later, when Don accepted the Wyoming Governor’s Arts Award for James Bama in 2021, he would tell this exact story.

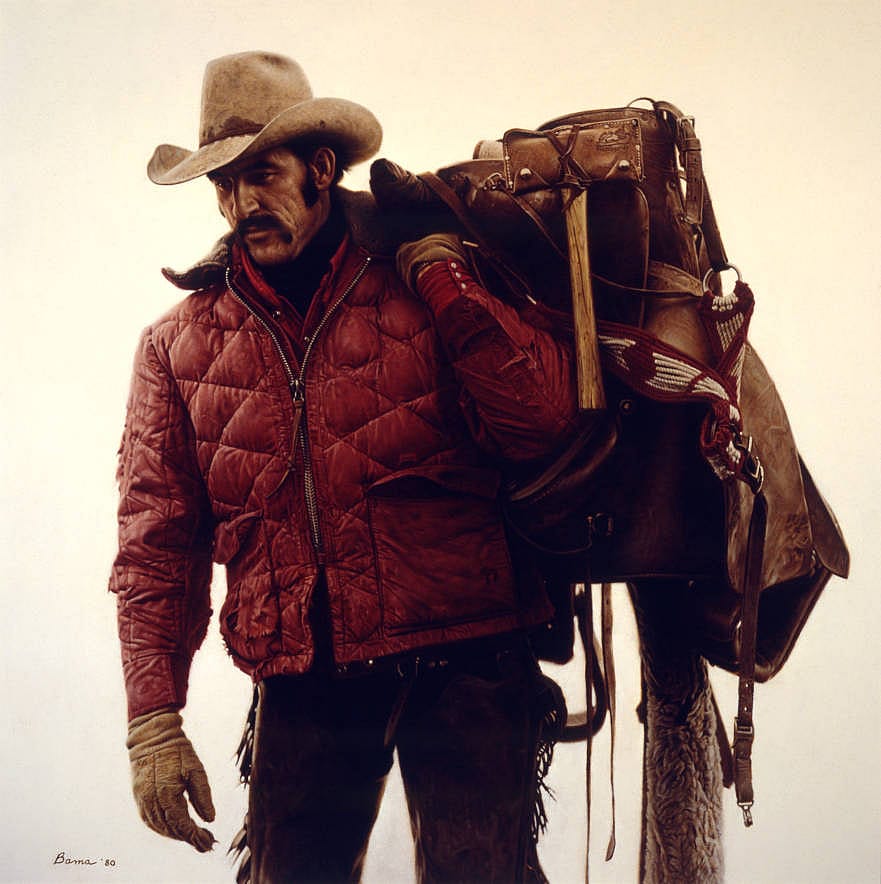

“Fifty-five bucks,” Don thought. “That’s not too bad for a few hours [work].” Don Schmalz and the other cowboys Jim photographed and painted thought it was a pretty good deal, but for James Bama, it was the culmination of the work of a lifetime.

James Bama grew up in New York City, the child of Russian immigrants. He was, as a kid, sports-crazy. He also liked to draw. He studied the covers of pulp magazines, Flash Gordon Strange Adventure and Tarzan. When Jim was fourteen years old, his father died of a heart attack. From this point on, he had to work to support his family, but Jim also managed to get into the High School of Music and Art. He sold his first work at fifteen, a drawing of Yankee Stadium, to The Sporting News.

After World War II, Jim lived with his uncle, sleeping on a cot in a tiny New York apartment. He entered the Art Students League on the G.I. Bill, and commenced a career as an illustrator. Twenty years later, countless advertisements, magazine illustrations, and paperback covers behind him, Bama and his wife Lynne arrived to visit his friend, artist Robert Meyers, on his Wyoming ranch.

Lynne had been encouraging Jim to make the transition to fine art. He wanted to paint people with character. One of his heroes was Andrew Wyeth. He wanted to go to the Maine Coast and paint fishermen. Cody stuck in his mind, though, and instead he and Lynne moved out here to live in 1968.

There is little that is so admirable as consistency. In the past several weeks my colleague Cassandra Day and I have interviewed over fifteen James Bama models, and their depiction of Jim’s personality and character is so consistent you could take any one of them to suffice for the whole. In living here over fifty years, his habits remained those of a sports-crazy New Yorker, attending local high school football and basketball games. He kept a punching bag in his yard and was a fitness fanatic. He liked inviting his cowboy models, or anyone at all, to feel his bicep. I have asked if Jim ever took up hunting, fishing, or hiking, but it doesn’t seem to be the case. When we went up to Jim and Lynne’s house a few years ago to pick up the photographs that he was transferring to the McCracken Library, he told me that he worked six and a half days a week until he had become too blind to paint.

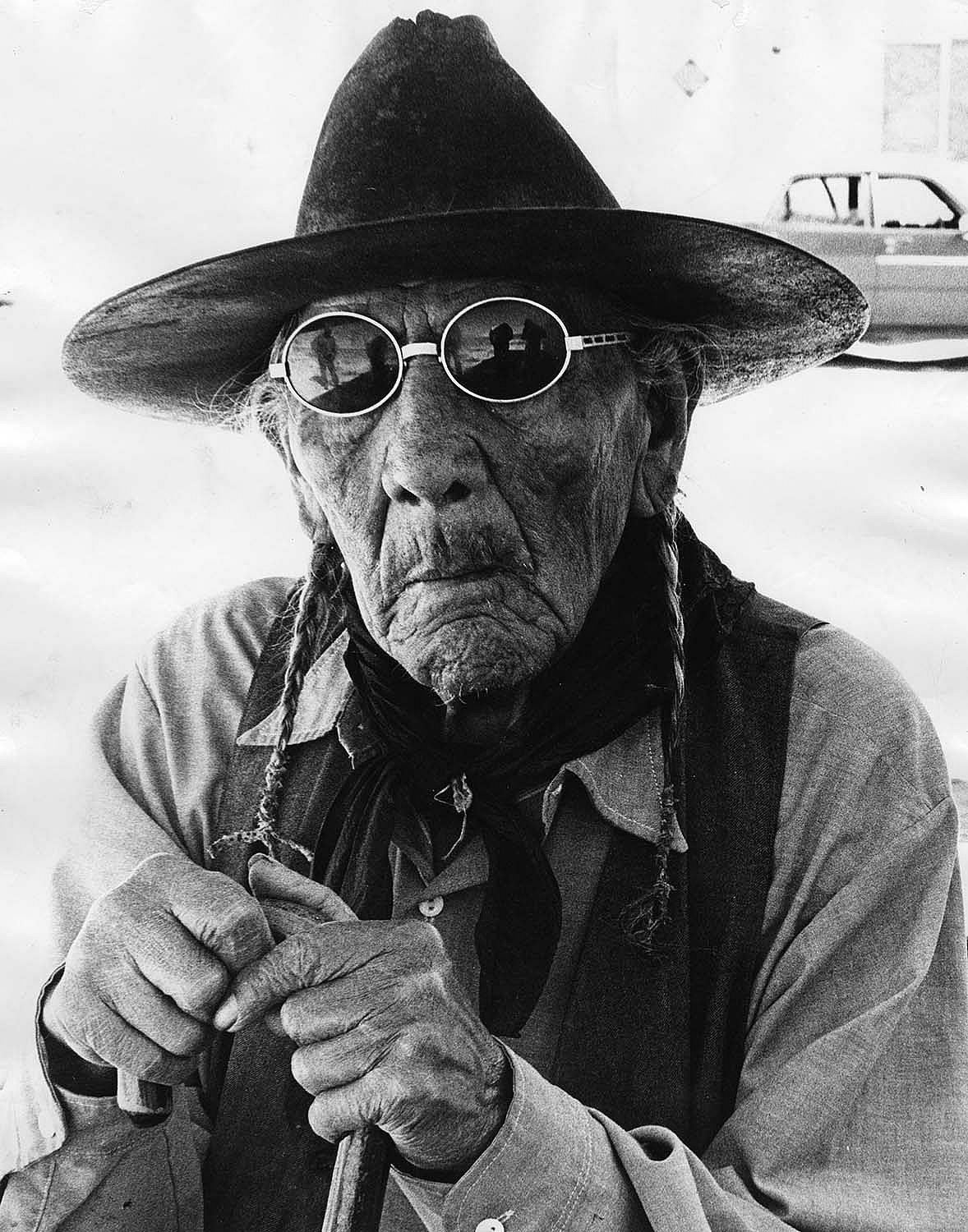

For the past several months, Whitney Western Art Museum Curators Susan Barnett and Ashlea Espinal have been busy in the McCracken Research Library, going through box after box of Jim Bama photographs in preparation for the exhibit, James Bama’s Photographs: Portraits of the West. They are labeled, “Mountain Men,” “Cowboys,” “Women,” “Hunting Guides.” Jim saw something in these people that he wanted to bring out. Cassandra and I asked his subjects if Jim staged them in any way, or asked them to wear specific clothing.

“Not really,” says Wes Livingston. “Jim would just say, ‘Bring your saddle, your duster, your raingear, your rifle.’ I guess I didn’t look at it as a prop because that was the gear we went to the mountains with. You just pretty much showed up in what you always wore. It was very realistic. There wasn’t any make-believe or made-up stuff.”

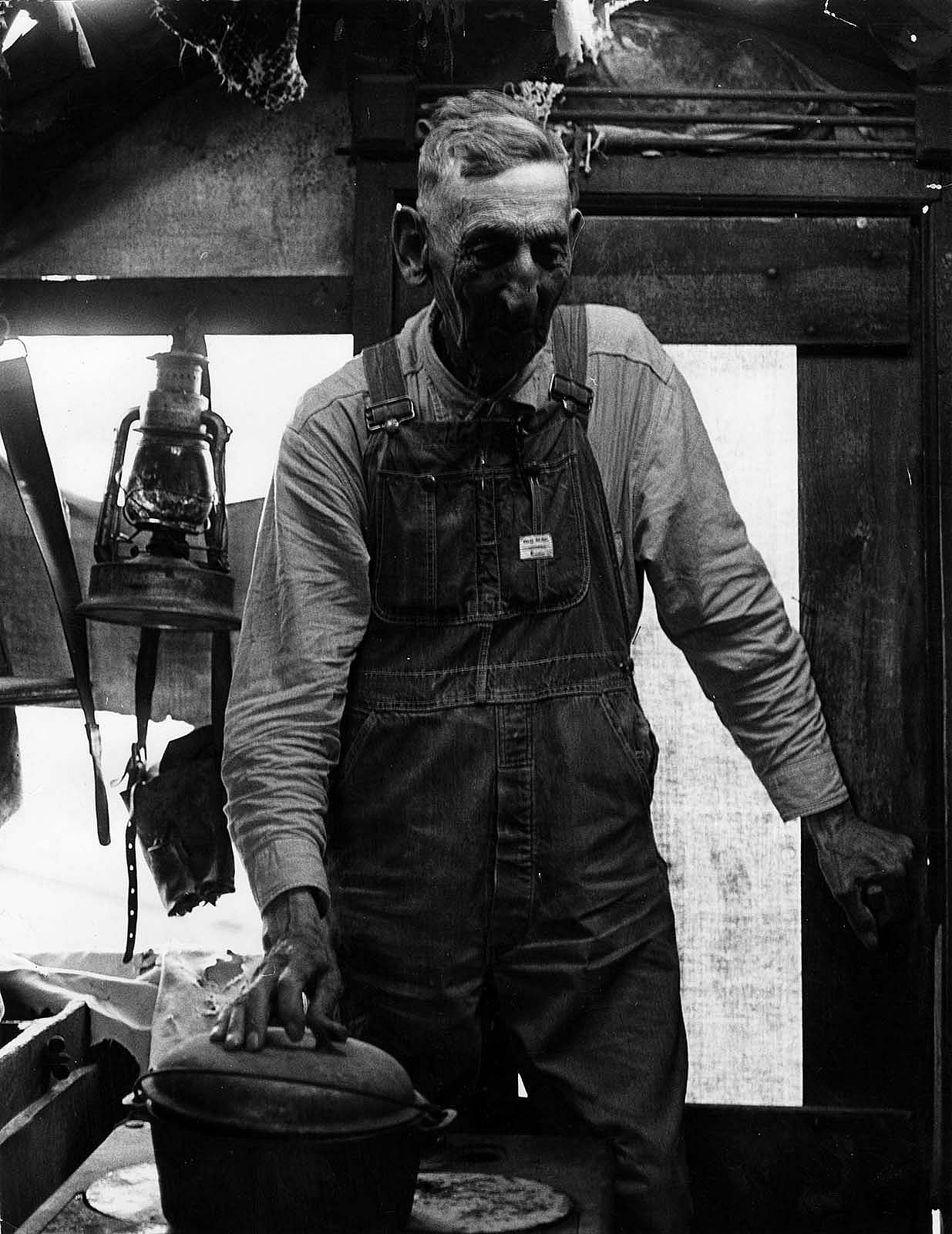

While Jim mentored artists such as George Dee Smith, Ken Blackbird and Sven Lindauer, his artistic focus was on cowboys and hunters, rodeo people and Indians. He particularly liked painting really old people: “I always wanted to paint old people, like Norman Rockwell,” Bama said. His models included Francis Setting Eagle, who at the painting was the oldest living Arapaho Indian, and Roy Bezona, who was born on the day Wyoming became a state, July 10, 1890.

When Rick Stonehouse was a kid, his dad, Mel, was managing the Cody Nite Rodeo. “We were basically there every day,” Rick says. “I remember [Jim’s] presence at the rodeo grounds, because he was obviously not in his element: here’s this guy from New York, with a camera. And I do recall that at first I think it was a little odd that he was there, and then it didn’t take long until everybody loved him.

“Because he wasn’t just there as an outsider. He wanted to get to know people. And he was really good about telling his story. He immersed himself very quickly and where there may have been a little bit of awkward time where it’s like, ‘Who is this guy and what’s he doing here?’, pretty soon everybody knew him, loved him. It was just like he was just a part of it.”

Jim Bama may have been from another culture, and his models may not have understood exactly why he wanted to paint them, but it’s hard not to love someone who is completely true to themselves. When a wealthy capitalist offered Bama two million dollars to do his portrait, he said no. Jim wasn’t painting for money.

Lee Livingston, Wes’s brother, says, “I honestly think that he had a soft spot for out-of-work cowboys. I think he had a sixth sense of when a guy was down and out. ‘Course, in the wintertime, it’s pretty easy to guess that cowboys and hunting guides are going to be short on work. But he would show up or give a call or leave a message at my Dad’s house that he wanted to do a photo shoot with me, and it darn sure helped with expenditures throughout the winter.”

James Bama did not consider himself a Western artist. “I painted a lot of old-time Westerners… people with wrinkles, but I painted them as people. That they were Westerners was incidental.

“During the many years of being a professional artist I’ve often been asked to express my opinions on art and to explain my working methods,” Jim said. “I would much rather have my work speak for me.”

“Those who got to know Jim had a really exceptional experience because basically, you became his friend,” says Ken Blackbird. “I look back at that photograph, those paintings, [and] I’m really glad I did that.”

James Bama’s Photographs: Portraits of the West, will be on display in the John Bunker Sands Photography Gallery from October 21, 2023 – August 4, 2024.

Cassandra and Eric would like to thank all the Bama models and colleagues who gave so generously of their time and memories for this exhibit: Sven Lindauer, Rick Stonehouse, Dan Deuter, Del Nose, Doug Mikkelson, Larry Leibel, Gary and Dede Fales, Rick Williams, Don Schmalz, Lynne Bama, Lee Livingston, Wes Livingston, Jerry Hodson, Ken Blackbird, and Jerry Kinkade.

Written By

Eric Rossborough

Eric has been rooting around the West since he took a job at the McCracken Research Library. Eric comes here from Wisconsin, where he worked at a public library, and enjoyed working on prescribed fires and fishing for bass and bluegills. He has a lifelong interest in natural history and the Old West.