Charlie Russell’s Tough Year

1917 was a tough year for Charlie Russell. His good buddy, bullwhacker Johnny Matheson, was dying. Johnny ran the last horse-drawn freight line between Great Falls and Fort Benton. Charlie enjoyed going with him periodically on his nine-to-fifteen day run. One time, they got snowed in. Charlie wrote, “We didn’t turn a wheel for three days, but we was comfortable. John slept in his cook cart, an’ I in the trail wagon, an’ there’s no better snoozin’ place than a big Murphy wagon with the roar of the storm on the sheets. Nature rocked my cradle and sung me to sleep.”

Charlie went to Chico Hot Springs to say goodbye to him. Johnny would visit Charlie periodically at his Great Falls studio, but would try to time his visits for when Nancy, Charlie’s wife and business manager, would be absent. He didn’t like to use a toilet. If there were women other than Nancy present in the house, Johnny wouldn’t go in at all.

The model of paintings like The Jerkline represented the last of the Old West, the one that Charlie now lived in in his head for the most part. “[T]hirty seven years Iv lived in Montana, but I’m among strangers now,” he wrote. And in August, Charlie and Nancy received word that Charlie’s dad had died of a stroke.

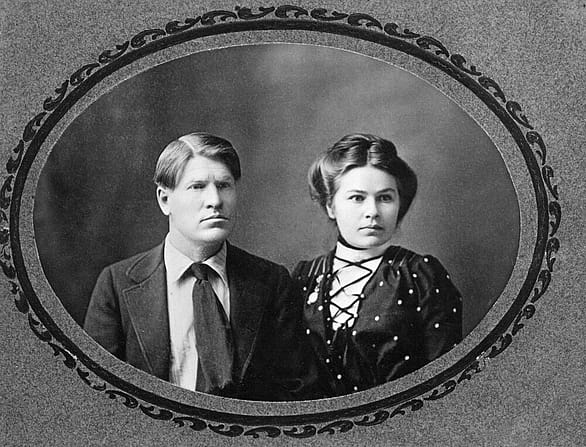

Charlie Russell had repeatedly attempted to run away from home to go out West before his parents finally shipped him to Montana Territory in 1880 with a family friend. He was sixteen years old. They may have thought a few months of the gritty life would shake it out of him, but he stayed. In spite of this, he was not what you would call rebellious, more the subject of an overwhelming fascination and impulse. He stayed in touch with his St. Louis family, visiting and writing. When Charlie wrote home to say he was getting married, his father wasn’t sure about the deal. At that point Charlie had been a cowboy for thirteen years. His son didn’t even live in a house. How was he going to settle down?

But he did, and when Charlie and Nancy chose a home they picked Great Falls: a bit of an odd choice for a cowboy artist. Russell Senior visited his son in Montana in 1898, had a suit made for him, and offered financial help. Great Falls didn’t have the most Western vibe. Charlie had made earlier forays to Great Falls in an attempt to get his art career off the ground, and Albert Trigg, an English saloonkeeper, saw promise in the young man, letting him sleep in back of his premises and helping him sell his work. When Charlie and Nancy picked a house site, they chose a spot a few doors down from the Triggs.

Albert and his wife Margaret functioned as sort of surrogate parents for the young couple. Nancy, an orphan, called them “Father” and “Mother.” When Nancy had a studio built in the form of a log cabin for her husband, Charlie was embarrassed. He worried what the neighbors would think. He wouldn’t go near the place until Albert came over. “Say, son,” Albert said, “let’s go see the new studio. That big stone fireplace looks good to me from the outside.” This became the place where Charles M. Russell did his greatest work. Charlie would cook dinners in the fireplace, of beans, biscuits, and wild game, proper Old West food, for people like Johnny Matheson and other holdouts who would come by to visit. Charlie Russell was not a man who lived in the present.

Albert and Josephine, who were English, with British accents, represented the upper class background that Charlie came from. He and Nancy were more than willing to capitalize on this background to get his art career off the ground. Josephine taught Nancy how to set a table and the basics of etiquette. All this came in handy as she piloted her husband’s career to New York and overseas, turning him from underemployed cowboy who traded his paintings for drinks into an international celebrity.

Thus, the death of Albert Trigg in April and Johnny Matheson in June of that year must have hit Charlie awfully hard. He had been born soon enough to catch the tail end of the Old West; now he was out of his element completely.

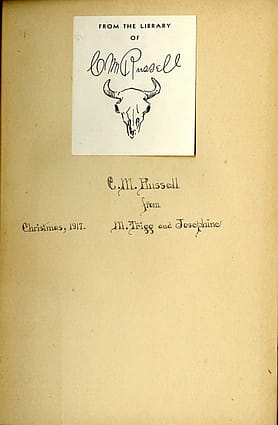

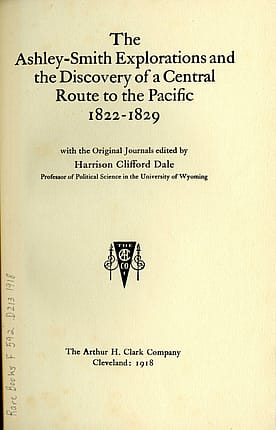

For Christmas, Charlie received a book from Margaret Trigg and her daughter Josephine. Albert’s name is conspicuously absent from the inscription. The Ashley-Smith Explorations and the Discovery of a Central Route to the Pacific, 1822-1829: With the Original Journals. This thoughtful gift is just the kind of thing Charlie would use in research for his work, and his own pleasure reading.

In 1926, after her husband’s death, Nancy Russell sold Charlie’s log cabin studio to the City of Great Falls for a dollar and moved to Pasadena, where they had spent the last several winters as Charlie’s health declined. It was there that upon Nancy Russell’s death in 1940, Charlie’s book collection was dispersed, via Dawson’s, a bookseller specializing in Western Americana. Many of Russell’s books ended up in the McCracken Research Library, including this one.

There is a lot encoded in this book, in this inscription. Charles M. Russell was a man who lived in the past. He referred to cars as “skunk wagons” and regarded modern appliances such as telephones with suspicion. One time Charlie was asked to be a speaker at the Montana Pioneers Association. The speech was short and to the point.

“I have been called a pioneer,” he said. “In my book a pioneer is someone who comes to a virgin country, traps off all the fur, kills off all the wild meat, cuts down all the trees, grazes off all the grass, plows the roots up, and strings ten million miles of barbed wire. A pioneer destroys things and calls it civilization. I wish to God this country was just like it was when I first saw it and that none of you folks were here at all.” That was the end of the speech. They didn’t ask him back.

This book is about the Ashley men. The first large fur brigade to go up the Missouri, when there were no dams and the brown water ran free with torn up trees, stumps, and dead buffalo. No buildings at all. The book is about a bygone era that, as far as Charlie Russell was concerned, was better.

The inscription shows the other side of his personality. The family man, the devoted neighbor, who lived in a house with his wife, whose neighbors showed the proper decorum he and his wife would need for artistic celebrity, and whose father, a successful manufacturer, aided and abetted his rise as an artist by using his connections to place Charlie’s work at the 1903 St. Louis World’s Fair. Sitting and looking at this book, he could bask in the love and attention of caring friends and relatives, and at the same time pine for a life that had completely passed him by while he was still on the planet.

This book came to us via the beneficence of Mary Clark Hiestand, whose father, Charles G. Clarke, was an avid book collector and swept down upon Dawson’s to snatch up many of the books in Charlie’s collection. You can read more about Charles G. Clarke and his adventures here. Delivered from the Los Angeles heat to the plains of Wyoming, these books, replete with book plates, are available for patrons to peruse here. I like to think Charlie would at least be pleased about that.

Written By

Eric Rossborough

Eric has been rooting around the West since he took a job at the McCracken Research Library. Eric comes here from Wisconsin, where he worked at a public library, and enjoyed working on prescribed fires and fishing for bass and bluegills. He has a lifelong interest in natural history and the Old West.