Ned Buntline and the Discovery of Buffalo Bill; or, how a Miscreant Created the First World Celebrity

One thing I’ve learned since coming to work at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West is that every prominent American frontiersman is that way for a reason, and that reason is usually that an author paid attention to them. John Filson was a Pennsylvania schoolteacher; when he acquired 13,000 acres of land in Kentucky he wrote a tome featuring the adventures of Daniel Boone in order to encourage settlement. When Boone was an old man he would have his grandchildren read to him from Filson’s work and sarcastically proclaim, “Every word true! Not a lie in it!”

Kit Carson became famous when he was riding a flatboat up the Missouri River: having dropped off his part Arapaho daughter with relatives in Missouri, he was on his way home. Also aboard was explorer John Fremont. Fremont was looking for a guide for a scientific expedition to explore South Pass and the Wind River Mountains. Someone pointed to Carson. Such a slightly built, quiet individual couldn’t be the person he was looking for.

But he was, and Fremont featured Carson prominently in his newspaper accounts of the expedition. Carson, like Boone, was something of a loner, and indifferent to his new celebrity. Kit Carson became the hero of many dime novels, but he couldn’t even read. Neither of these guys took any interest in their newfound fame, and continued to go their way as they had, for the rest of their days.

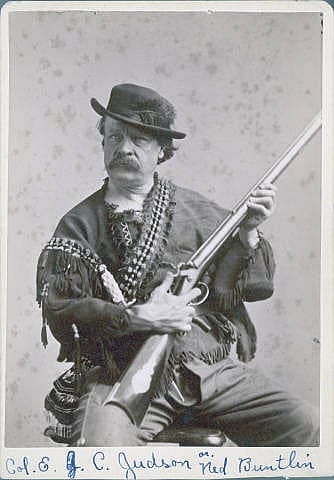

On or about July 16, 1869, Ned Buntline got off the train at Fort McPherson, Nebraska. Ned was coming off a California lecture tour that had crashed and burned. His lecture topic had been temperance, a growing movement that culminated in the eventual passage of the National Prohibition Act in 1919. The problem with Buntline’s tour was that he frequently appeared drunk in public, sometimes giving his lectures in an inebriated state. “His career as a temperance lecturer in California was a failure,” said the Oakland Daily Transcript. “Although heralded with great flourish of cold water bugles, and his lectures largely advertised, he drew very small houses, and few of those who went to hear him once ever attempted to kill a spare hour in the same murderous style again.”

Buntline had a plan at Fort McPherson, though. As a writer of popular fiction who grossed the unheard-of sum of $20,000 a year, he was looking for new material, and he sought out Frank North, a scout who had played a signal role in the recent Battle of Summit Springs.

The story goes, North had no interest in celebrity either. He pointed Buntline to a long-haired man sleeping in the noonday heat underneath a wagon, “That’s your man, right there,” North said.

This story is awesome, isn’t it? Another taciturn frontiersman who didn’t care about being famous pointing out someone who did, and this someone, Bill Cody, became America’s first worldwide celebrity as a result. Except that the story probably isn’t even true. Nevertheless, Buntline and Cody somehow found each other, and a hack writer and a skilled but anonymous scout were on their way to immortalizing each other.

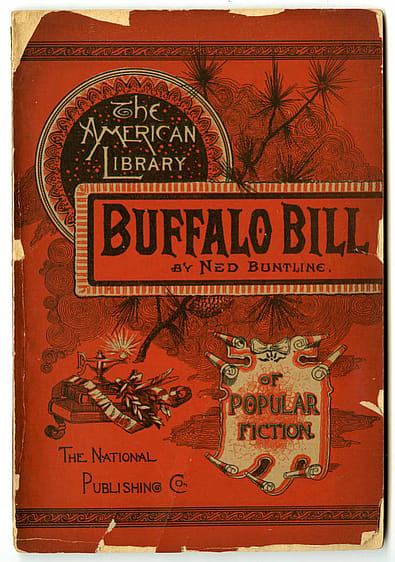

Just try reading the resulting book, Buffalo Bill: The King of the Border Men. I did. It’s two hours of my life I’ll never get back. To the contemporary reader, Buntline’s book is absolutely unbelievable, not in the factual sense, although it is that, but it’s unbelievable that anyone would actually want to read it. Buntline doesn’t assume perceptive qualities on the part of the reader. Young Cody arrives at the home of his mother and sisters: a quiet, domestic expanse; a pretty white cottage with trellised bowers of vines and climbing roses, reminding us that Buffalo Bill was not a homeless frontiersman who went for years without seeing his family. One time Daniel Boone arrived “home” to the stockade where he had installed his family, only to find his wife, Rebecca, had gone back east over the mountains. He had been gone for so long she merely assumed he was dead. In Buntline’s fiction, young Cody is tied to the domestic expanse, the defender and protector of female pulchritude and his absolutely sweet female relatives.

He’s got two friends in tow, Wild Bill “Hitchcock” and Dave Tutt. Buntline writes, “Three more perfect men, in point of personal beauty, never trod the earth.” In case you can’t figure out who the bad guy is, Dave has “a sensual expression about his mouth so utterly different from the other two, and a fierce, passionate longing in his eyes, which made the two girls, instinctive in their purity, shrink from him.” After dinner, someone starts shooting at the house. Buffalo Bill and Wild Bill rush out to deal with the situation, while Dave hides.

The book was a hit, and Buffalo Bill interrupted his frontier career, which consisted of scouting for the army and guiding celebrities like the Grand Duke Alexis, to head east for a trip to New York, where he found he had become a celebrity himself. Wined and dined, the highlight of Cody’s trip was a viewing of Buntline’s dramatization of his life at the Bowery Theater. When the audience found out the subject of the play was in the audience, they cheered and called for a speech. Out on the stage, Cody found himself at a loss for words. This was the beginning of Buffalo Bill’s show business career.

Cody returned to the West, but Buntline kept writing him. He saw money in Buffalo Bill, and told him so. At length, in the fall of 1872, Cody and a friend, Texas Jack, arrived in Chicago, where they met Buntline and a theatre promoter. Buntline was supposed to furnish scouts, along with twenty “real Indians,” along with a play. Buntline had the scouts, but no Indians, and no play. It was Thursday, and the play was supposed to open on Monday.

Ned calmed the irate promoter by renting the theatre himself. He produced the play, Scouts of the Prairie, in four hours, lying on the floor of a hotel room with pen and paper while Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill watched. They were completely out of their element. Ned hired twenty unemployed actors to play the Indians, cast himself as Cale Durg, a trapper, and hired an Italian dancer, Giuseppina Morlacchi, to play the Native American female love interest. Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill played themselves.

The produced-in-four-hours script of Scouts of the Prairie turned out to be unheard, because Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill couldn’t learn their lines. They weren’t actors. Not yet, anyway. The two of them stood on stage dumbfounded.

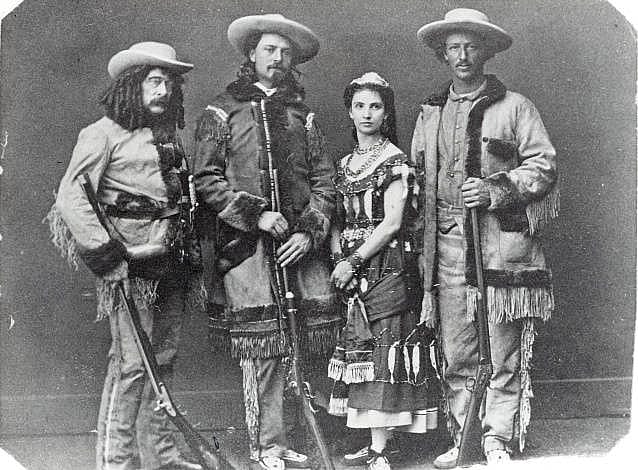

Left to right: Ned Buntline, Buffalo Bill, Giuseppina Morlacchi, and Texas Jack.

“Where have you been, Bill?” Buntline, as Cale Durg, finally prompted him.

Cody looked out in the audience and saw a Mr. Milligan. Milligan was a businessman who Cody had guided.

“I’ve just been out on a hunt with Milligan,” Cody started.

Milligan was a known figure in town and the crowd roared. Cale Durg, or Buntline, continued prompting Texas Jack and Cody with questions, and that was the play.

A hit! People were willing to pay good money to look at real live Westerners. “A horrible mass of rubbish,” The New York Times said. Another reviewer called it an “intolerable stench.” The [Chicago] Daily Herald wrote that it was about “Everything in general and nothing in particular. Everything was so wonderfully bad it was almost good,” making Ned Buntline the Ed Wood of his time. The play toured the East Coast for two years to sellout crowds, and in a way, Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill were already gone from the West for good.

Ned Buntline’s 1869 venture was his only trip West. He was not a Westerner, or a Wild West buff, and did not seem to foresee the hold the Western would have on the popular imagination. Buntline wrote only four titles on Cody, a tiny fraction of the hundreds of books he churned out: sea stories, seamy accounts of the New York underworld, hunting and fishing stories, vicious personal attacks in the pages of his intermittent newspaper, Ned Buntline’s Own. But today he is primarily remembered for being the man who discovered Buffalo Bill, wrote about him, and put him on stage for the first time.

Giuseppina Morlacchi and Texas Jack got married and moved to a farm in Massachusetts. Cody did such theatre as has been described here for ten years until launching his Wild West. Buffalo Bill was certainly grateful for the turn Ned Buntline did him. He wanted to name his son after Ned, but Frank North talked him out of it. At Frank’s suggestion, Cody named his son: Kit Carson.

Written By

Eric Rossborough

Eric has been rooting around the West since he took a job at the McCracken Research Library. Eric comes here from Wisconsin, where he worked at a public library, and enjoyed working on prescribed fires and fishing for bass and bluegills. He has a lifelong interest in natural history and the Old West.