The Banditti of the Plains, or, the Triumph of the Nesters

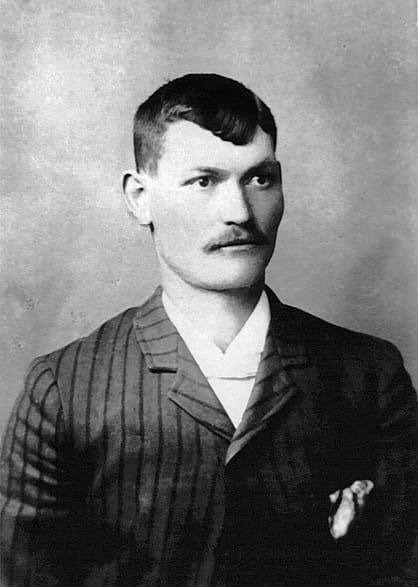

On Friday, April 8, 1892, Ben Jones and Bill Walker rode down out of the Bighorn Mountains. They had been trapping for weeks. Ben Jones was a cook in cowboy camps, Walker a hand, and they had improved their winter-time by heading into the backcountry to procure furs. They had done well: with what they had caught, it would be a nice chunk of change, better than they could get working for ranches. They rode up to the KC Ranch. They had stayed a night here on their way in. One of their hosts, Nate Champion, had talked about how established ranchers resented his presence, but Nate wasn’t scared of anything.

Entertainment, not to say company, was scarce in the West, and Walker was a musician. This made him and his buddy particularly welcome, although Nate Champion, and his partner, Nick Ray, in their rural isolation, would have been happy to see almost anyone. Champion and Ray made the host request. After a nice dinner of steaks and biscuits, Bill Walker broke out the fiddle. They stayed up late into the night. They played all the old hits: “The Pretty Quadroon,” “Sweet Betsy From Pike,” “The Ship That Never Returned.” They drank most of a bottle of whiskey and had a hell of a time. In the morning, after a couple hours sleep, Ben Jones woke up and went out to get water for breakfast. After an hour passed and Ben Jones didn’t return, Walker went out to find him.

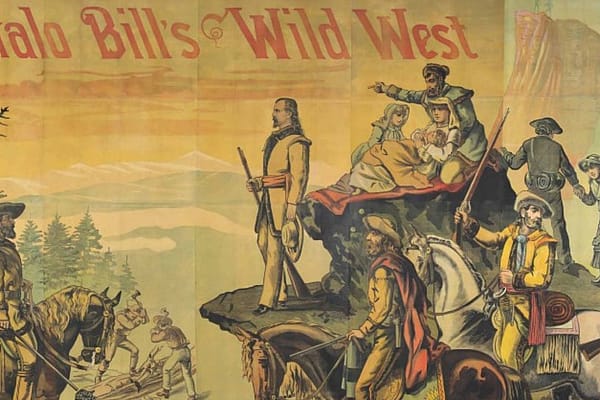

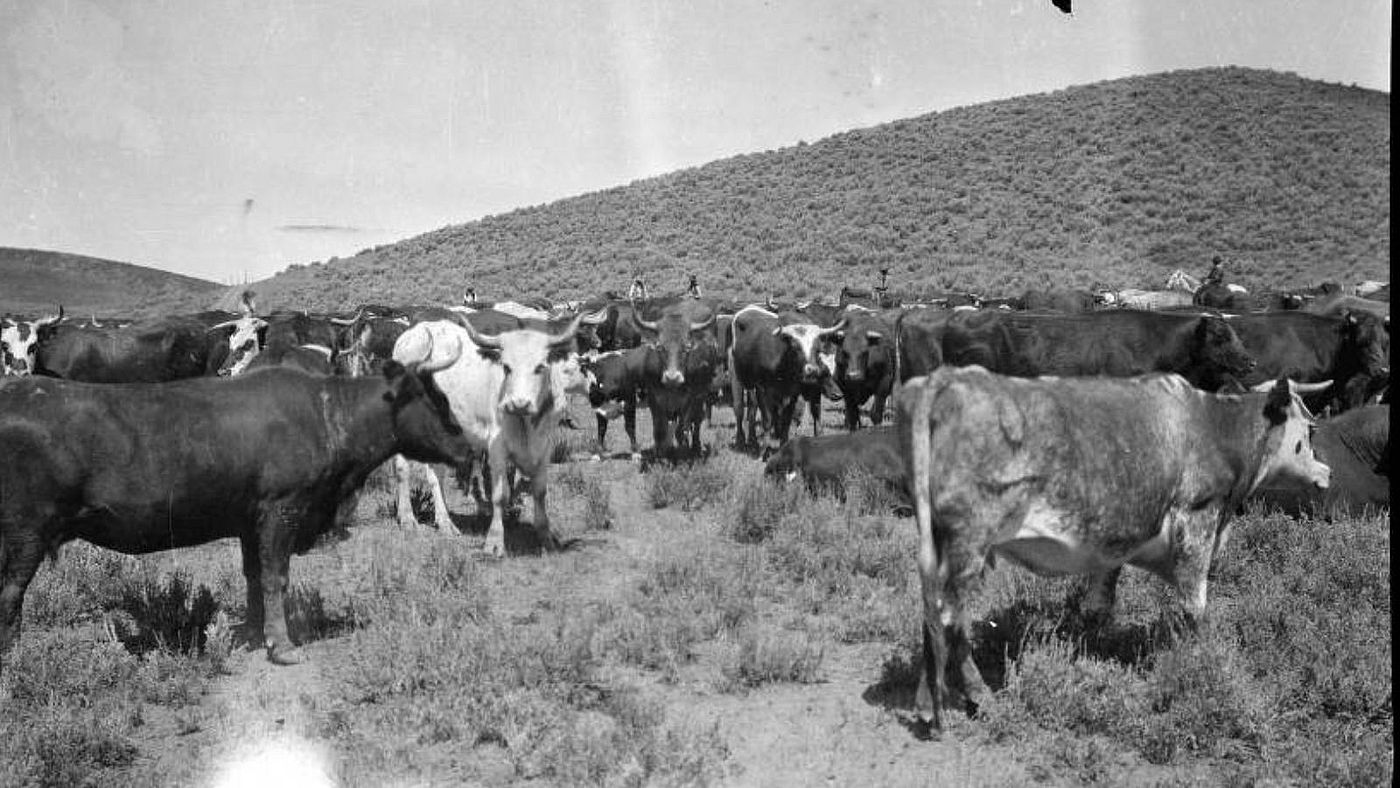

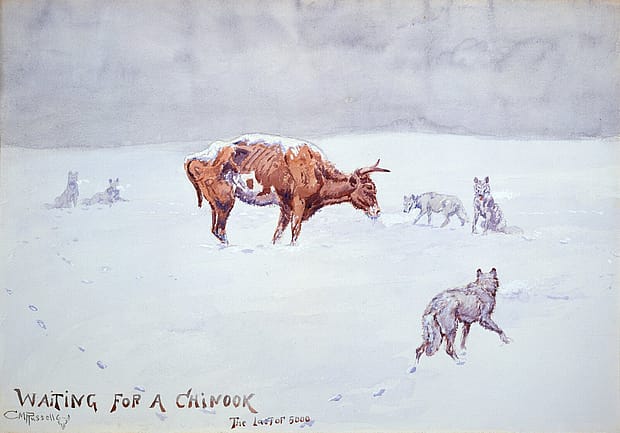

Bill Walker found himself facing the barrel of a rifle. These two itinerants had wandered into the middle of a range war. Exasperated with “nesters and homesteaders,” the established stockmen of Wyoming had decided to clean house. Or, at least, what they considered to be their house, the plains of Wyoming. The open range system of fenceless expanse dominated by cattle barons and their minions, the working cowboys, had never really recovered from the brutal winter of 1886 – 87. A winter so cold that entire herds froze to death and wiped out some ranchers in total. This winter, incidentally, was the winter that gave Charlie Russell his start as Montana’s Cowboy Artist. Charlie’s employer just didn’t know how he was going to tell his English investors what had happened. Charlie made a small painting for his boss to send in the letter. Charlie’s boss took one look at Charlie’s piece and sent it alone. This was the turning point that turned Charlie Russell from night-herd to international celebrity.

But this is not a nice story about a talented man who gave the world pictures of what he deemed to be a happier era. The Wyoming Stock Growers Association was facing economic marginalization at the hands of a horde of “nesters” who were homesteading along the watercourses and taking up the country. They wanted the range the way it was, with no fences, and the profits for themselves. The Wyoming cattlemen decided to start their cleanup of the range with the elimination of the redoubtable Nate Champion, who spent the day of April 9, 1892, sequestered in the KC Ranch house while gunmen imported from Texas kept him pinned down with gunfire. Walker, who was held in the horse stall, watched in horror as Nate’s log house was set afire. Nate made a run for it. Today there is a statue of Nate Champion in the nearby town of Buffalo, Wyoming. The Texans were impressed by Nate’s utter fearlessness. “By God, [Nate Champion] may be a rustler,” said the Texas Kid, “But he is also a HE MAN with plenty of guts!”

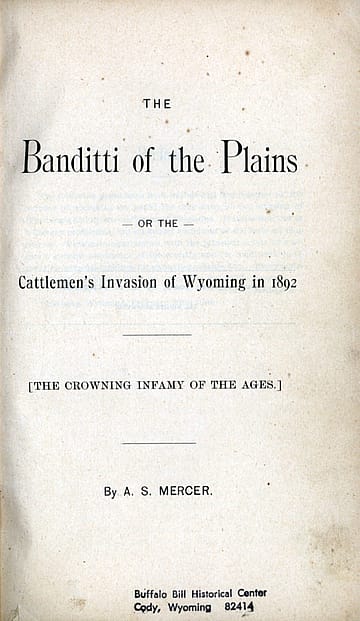

In 1995, local historian Clay Gibbons gave a talk to a Forest Service crew. At the end, a woman approached him. “I have something in my possession I think you should have,” she said. A few weeks later a package containing a binder full of yellowed paper arrived at Clay’s house. The Banditti of the Plains, it said at the top.

Clay couldn’t believe it. Was this the original manuscript on the Johnson County War? The book that had been suppressed for decades, on the range war that was inspiration for novels like The Virginian and movies like Shane and Heaven’s Gate? How would he ever figure it out? Clay had a living to earn. He had demands on his time. Clay put the manuscript in a dresser drawer full of socks, and forgot about it.

But it burned in the back of his mind. And one day, while I was sitting at my desk, a call came from Admissions. There was a man named Clay Gibbons to see me. Had I heard of him? He wanted to talk about a book.

I certainly had. I was a fan of his excellent podcast, The Sweet Smell of Sagebrush. Clay greeted me upstairs. A library is a place to sort out the tumult of history in a peaceful setting. The museum was quiet in winter, the rotunda with its mounted grizzly bear peaceful. Clay wanted to go over our manuscript copy of The Banditti of the Plains against his own. This book was ruthlessly suppressed, to the point where people copied it out and secreted manuscript copies so it would not be lost. Did Clay have the original? Did we? Clay and a friend spent five days going over each manuscript. Unless he could prove otherwise, Clay would have to assume both are typed manuscript copies.

It turns out our manuscript matches the 1923 edited reprint of Banditti titled The Powder River Invasion. So we know the McCracken Research Library’s manuscript is not the original.

Clay compiled a fifty-page report comparing his manuscript to our first edition of The Banditti of the Plains, which we also hold. Because the Wyoming Stock Growers Association burned every copy they could get a hold of, few copies of this first edition are in existence.

Clay mounted his next assault on the proscenium of hidden history with bookman extraordinaire Wally Johnson. Wally, the retired Chair of the McCracken Research Library Board and federal mafia prosecutor, worked as an attorney under several U.S. Presidents. I forgot to ask Clay whether he roped Wally in because of his expertise as a bookman or because he has a knowledge of organized crime. Anyway, the two of them spent several days going over our first edition and Clay’s manuscript.

“Clay identified 92 edits and interlineations which were incorporated in the printed book,” Wally says, “So how does the Clay Gibbon’s copy fit into the development of the book? The text as adjusted with the 92 edits and interlineations is identical to the printed first edition. That means the manuscript must have preceded the book. To do otherwise would require editing backwards!”

Does Clay have the original manuscript of The Banditti of the Plains? Based on documents currently available, it seems that the very first author-generated copy of this treasure of Wyoming literary history, a book that was ruthlessly suppressed for decades, has been found.

Ben Jones and Bill Walker ended up in Westerly, Rhode Island. The Wyoming Stock Growers Association for some reason did not see fit to kill these harmless woodsmen, but they did want them out of the way. They were installed in a boarding house run by a retired sea captain. Bill Walker hated it. “It would have been a pleasant place to live,” he wrote, “if we had been in a frame of mind to see it.” He continued, “A good fist fight or a second drink of firewater was enough for a man to get shaded away for ten days….The only real excitement I saw was one of those tall, one-wheeled bicycles and they could throw me farther and oftener than any bronc I ever cinched the leather on.” Walker later referred to his time in Rhode Island as two years out of his life that he wouldn’t get back.

Ben Jones fared better. To a point. Shaved and cleaned up, Ben presented a handsome fifty-year-old, and he got himself a girlfriend. They got married. With her income as a dressmaker and the money the Stockgrowers had promised Ben for his trouble, he would be sitting pretty.

When Jones and Walker were told they were free to go, and the promised checks bounced, Jones went out to Cheyenne to see what the matter was. He was never seen again.

Written By

Eric Rossborough

Eric has been rooting around the West since he took a job at the McCracken Research Library. Eric comes here from Wisconsin, where he worked at a public library, and enjoyed working on prescribed fires and fishing for bass and bluegills. He has a lifelong interest in natural history and the Old West.