Pommel & Pistol: A brief history of handguns on horseback – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall 2022

Pommel & Pistol: A brief history of handguns on horseback

By Danny Michael

Since the invention of firearms (or at least shortly thereafter), people sought to use them from horseback. Riding and shooting separately are each accomplished disciplines that require skill and practice. Doing both at the same time has been a skill that has helped determine the fate of military powers, and continues to captivate modern sport shooters.

The earliest firearms were simple tubes that required the user to hold a match to a touchhole. Matchlocks simplified the process, but keeping track of a match lit at both ends—along with spare gun powder and your horse—also kept these earliest firearms from being widely adopted for mounted use.

The first wheellock firearms emerged near the beginning of the 16th century. They proved much more complicated than their predecessors, but the guns were largely self-contained once loaded. Instead of a match contacting gunpowder directly, the wheellock could be loaded and primed, and it stayed in that state indefinitely, until the user fired. Wheellock shooters could keep them loaded and in a hoster, or wear them on a belt until needed, and could then easily draw, cock, and fire them.

By the 1540s, European armies began to integrate firearms into mounted formations. Germanic and Polish cavalry adopted wheellock pistols to arm formations of horsemen known as “Reiters.” They were typically equipped with a pair of pistols, and sometimes a long gun, in addition to wearing armor and carrying melee arms.

Reiters also set a precedent of carrying a pair of pistols in holsters affixed near or on the pommel of their saddle. One of their preferred tactics was the “caracole.” In this maneuver, horseman would advance in ranks toward an enemy formation, turn slightly to one side as they rode into pistol range, and fire a pistol. They would then turn toward the other side and fire their second pistol. After firing the second pistol, riders retreated to the rear of the formation to reload and then cycle back to the front. This tactic allowed Reiters to maintain a nearly constant fire on the enemy, and they could charge home with melee weapons to break the enemy’s line if they began to waver.

As firearms became more effective and more infantry started using them, Reiter-style cavalry began to fall out of favor. Cavalry in European armies began to split into distinctly melee-armed shock troops like lancers and cuirassiers, or firearm-armed troops like dragoons.

Fast forward to the early American Republic and consider the first years of the new national armories at Springfield, Massachusetts, and Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. The War Department formed its own dragoon units in the years prior to the War of 1812. To equip these mounted units, Harper’s Ferry Armory produced the Model 1805 pistol. This model was the first pistol made at a national armory in the United States, and it remains on the insignia for U.S. Army Military Police today. Relevant to mounted troops, the Model 1805 was made in and serialized as pairs. So, each Model 1805 bears the serial number of its twin, which presumably would have been issued together to the same mounted trooper to be carried in saddle holsters. The government first issued 1805s for the War of 1812, and the Regiment of Light Dragoons and various state-raised cavalry units used them.

Following the War of 1812, the U.S. government disbanded the Regiment of Light Dragoons, and the country went without any mounted units for the Army until the 1830s.

By the time of the Mexican American War (from 1846–1848), each of the U.S. dragoons carried a pair of percussion pistols, a Hall carbine, and a saber. Samuel Colt’s collaboration with Samuel Walker of Texas Ranger fame meant that some U.S. cavalry, namely the Regiment of Mounted Rifles, received the new Colt Walker revolver late in 1847. Sometimes also known as the Walker Colt, the new revolver became one of the best-known horse pistols. Revolutionary for its day, the mounted rifle troopers fortunate enough to get a Walker received a 6-shot revolver with a rifled barrel, while most cavalry members carried single-shot, smooth-bore pistols. The gun inherently had much more firepower than its predecessors and was accurate at much greater distances: 100 yards compared to 10 or 20.

This usefulness came at a price, though. All prior horse pistols would be considered large by modern standards, but the Walker took it to an extreme. Each Colt Walker weighed 4.5 pounds and needed to be carried in a pommel holster on the saddle, with a gun on each side of the pommel.

Refinements to the Walker would bring about some of the final American horse pistols: the Colt Dragoons. They were built slightly smaller than the famous Walker, but not by much. The overall weight was trimmed to a spry 4.25 pounds, and the barrel length drew down to a mere 7.5 inches. These were intended to be used as the Walkers were—still carried in pommel holsters on the saddle despite the reduction in size. The Regiment of Mounted Rifles used these Dragoon models, and the manufacturer also sold them to civilians in the years prior to the American Civil War.

Unfortunately, the revolution that Colt and other manufacturers brought to handguns in the mid-1800s would begin to diminish the need for horse pistols entirely. As materials and manufacturing improved, the guns could be made smaller and lighter yet retain the firepower of the larger pistols. Guns like the Remington New Model, Starr 1858, and Colt 1860 fired the large .44 caliber projectiles like the Walker and Dragoon did. But these newer models halved the weight of the gun, making it reasonable to carry in a belt holster.

By the time of the American Civil War, cavalry had largely abandoned pommel holsters in favor of a single revolver worn in a belt holster. To the dismay of quick-draw fans everywhere, cavalry wore their pistols on the right side with the grip forward and were trained to draw right-handed. The saber would be on the left, and drawn “cross-draw,” while the shooter would rotate the pistol as he drew it. This was not the fastest way, but cavalry units were not meant to fight “High Noon” style. Following the Civil War, pommel holsters virtually disappeared, ending the centuries-old class of “horse pistol.”

But the story doesn’t completely end there. The increase in popularity of action shooting sports has given fresh legs to mounted shooting traditions over the last few decades. Cowboy Action Shooting, Single-Action Shooting Society matches, and Cowboy Mounted Shooting created a need for horse pistols of sorts. In these competitions, shooters ride horses or mules in a pattern with 10 balloon targets. They must break the balloons with blank rounds fired from a pair of single-action revolvers. The blank rounds do not fire a projectile, but will still break a balloon and allow the competitors to ride and shoot safely. Of course, riding and shooting requires holsters, and the exact style and placement are left to the competitors’ preference. They can be worn on the rider’s body or on their saddle. While most competitors use smaller guns that some would call “belt-sized“ or “holster-sized” firearms, they can be mounted from the pommel like the horse pistols of old.

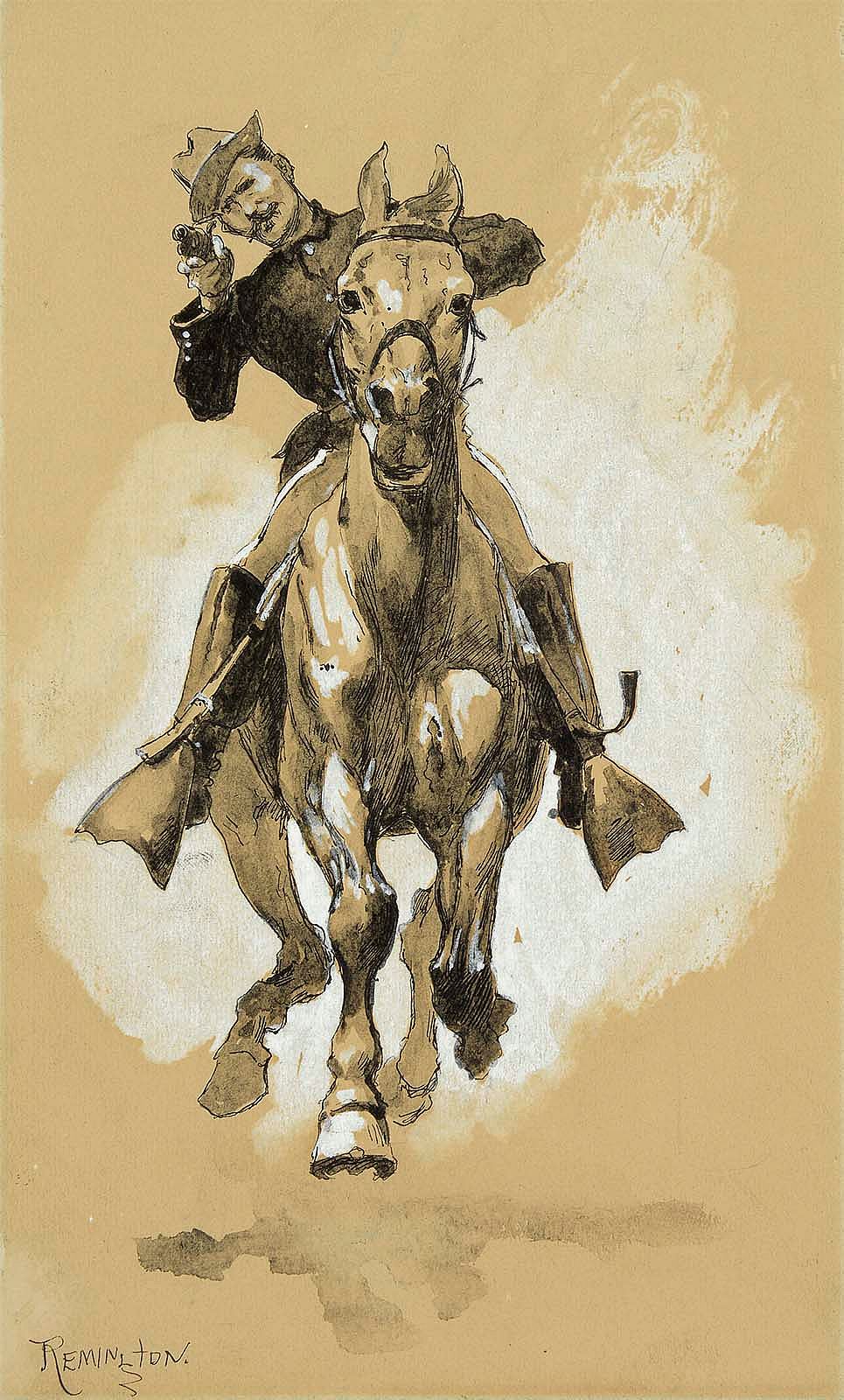

Finally, horse pistols occasionally find a home on the silver screen today. At least one major Hollywood Western made in the last several years used horse pistols in their truest sense (despite most movies and TV series depicting mounted shooting with inaccurate firearm models). In the 2010 movie adaptation of the novel True Grit, viewers see Jeff Bridges’ version of the character Rooster Cogburn drawing a pair of Colt Dragoons from a pommel holster for the final showdown. Set in the late 1870s, when metallic cartridge guns were readily available, this is not an entirely implausible scene.

Percussion revolvers and cartridge conversions of them lingered on even as more modern firearms became common. Although, historically speaking, the main users of pommel holsters and large horse pistols—the cavalry and horse-mounted soldiers—were not trained to charge home while firing both guns and holding the reigns in their teeth.

About the author

Danny Michael is the Robert W. Woodruff Curator of the Cody Firearms Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. He holds a Master of Arts from the University of Louisville.

While Danny doesn’t shoot cowboy mounted matches, he does enjoy action shooting sports and learning about military history.

Post 352

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.