Max Wilde first drifted through the Cody area in 1913. An Indiana farm boy, he was fascinated by stories of hunting and trapping in the West and far North. “When I saw all the game and the fishing Wyoming had to offer,” he said, “I knew I was hooked.” Wilde drove tourist wagons up the North Fork of the Shoshone River into Yellowstone and then cooked for a local dude ranch.

It was here that he met Ed “Phonograph” Jones. Born in Nebraska, Jones had cooked on a riverboat in the Pacific Northwest and then worked for Buffalo Bill Cody on his T.E. Ranch. “This is your home, Jones,” Cody told him. “Never leave it.” Phonograph didn’t. A larger-than-life character, Jones’ nickname referred to his propensity to talk constantly.

A Winter in the Backcountry

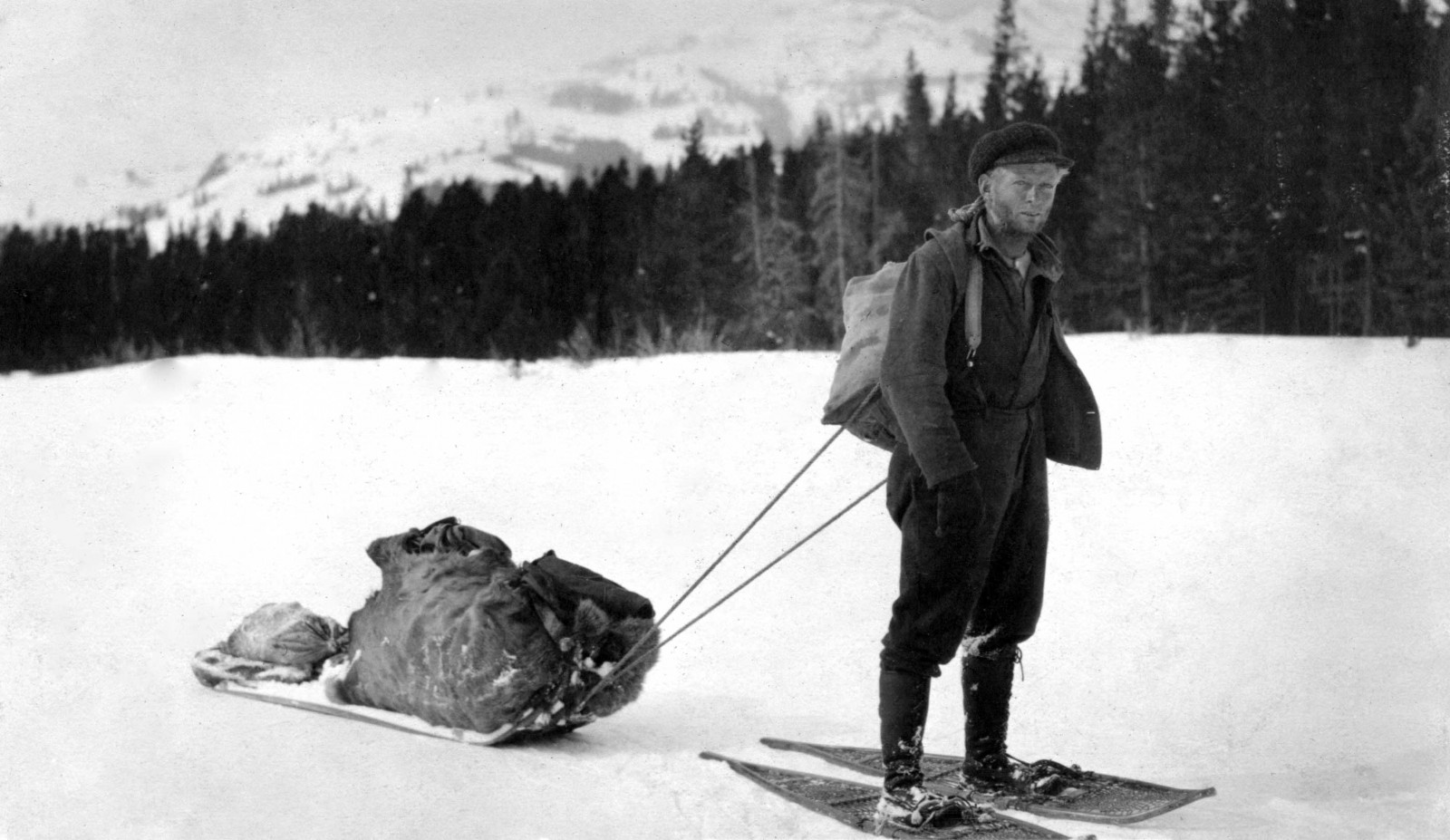

In the winter of 1918-1919, Phonograph and Max headed into the backcountry together on a trapping and hunting expedition. Their destination was the Thorofare wilderness southeast of Yellowstone National Park and more than twenty miles from the nearest road. Horses were used to pack in all the gear. After camp was established, the horses were turned loose, and they headed back to their home ranch on their own.

“We ran our lines on snowshoes and skis and we would see each other once a week,” said Wilde. “Elk was our meat supply, and we had box stoves and used grub caches. Beans were a big item and we had rice, plenty of coffee and dried fruit. We even baked our own bread.”

A Spoonful of Olive Oil a Day

The boys lived in tents all winter. The tents were heated with Yukon stoves. Beds were made with pine boughs underneath. Miles from medical help, Max and Phonograph took a spoonful of olive oil every day to ward off appendicitis.

When asked about the weather, Wilde quipped, “Never had a better winter. We used snowshoes only about half the time and some days it was shirt-sleeve weather.”

During the winter the only animal they had to worry about was moose. Phonograph told Don Bell, a local cowboy and guide, about a cranky cow moose with a calf. “Ever try to climb a tree with snowshoes on?” Phonograph asked.

Don Bell told him it was impossible.

Phonograph said, “It isn’t. Not when there’s a moose in your hip pocket.”

Their winter’s haul of marten, fox, and coyotes netted the two of them $10,000, which is $150,000 in today’s money. Wilde spent his share on a string of horses and became a backcountry guide.

Bathing in Icy Mountain Streams

Jones and Wilde remained friends for life. A dedicated cook, Jones spent each fall in Max Wilde’s wilderness camp and continued to travel the backcountry until he was in his eighties, bathing every morning in icy mountain streams. After Phonograph got too old for wilderness trips he continued to be seen bopping around town, cooking for various functions.

Max Wilde retired from guiding in 1959. During his career he piloted many celebrities and captains of industry through the wilderness. In particular he was known for guiding major league baseball players, including Hall of Famers such as Jimmie Foxx, Ty Cobb, Tris Speaker and others. At the end of his life Max said, “I wouldn’t take a million for the wonderful experiences I enjoyed trapping, hunting, fishing, and outfitting in the mountains of Wyoming. I’m just glad for the uncrowded years.”

The exhibit A Winter in the Backcountry, featuring more photographs of Phonograph Jones’ and Max Wilde’s adventures, is now on display in the Shiebler Library Gallery. Come check it out!