Originally published in Points West magazine in Fall 1998

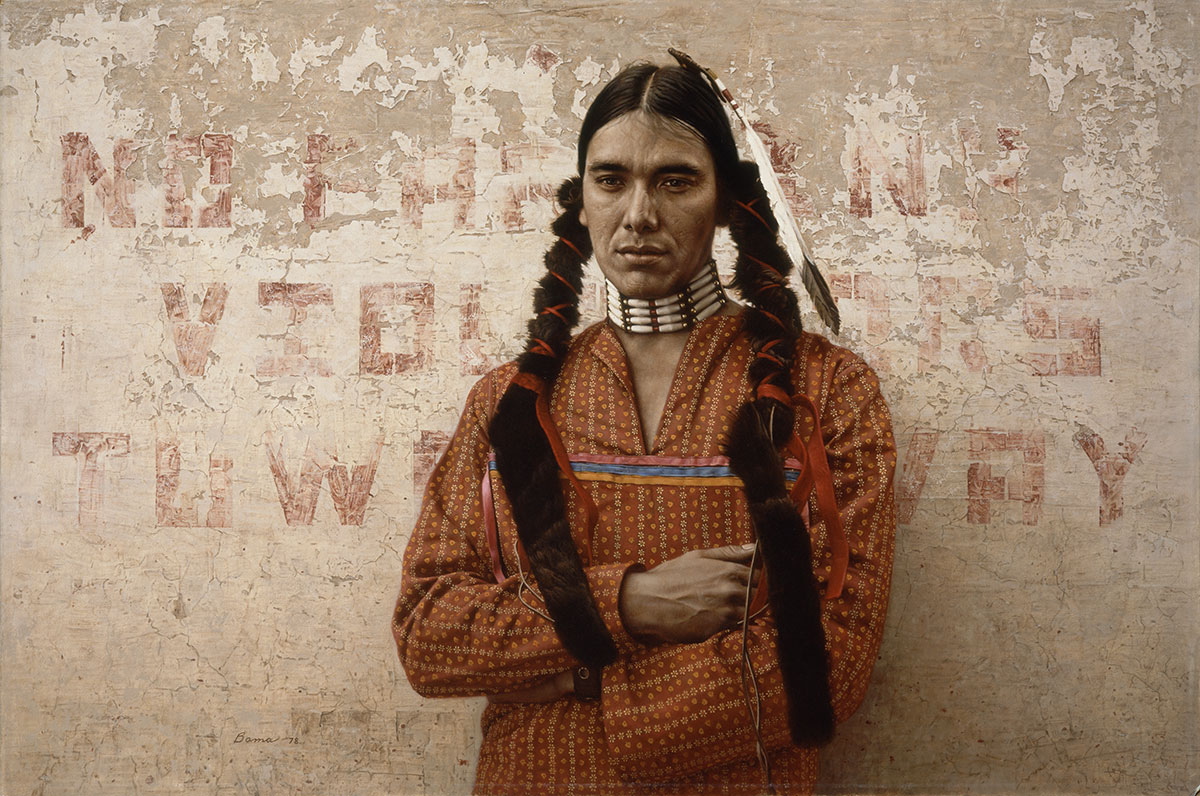

The Power of Images: Indian Revitalization Presents Unbounded Possibilities

By Dave Warren, Guest Author

Editor’s note: Dr. Dave Warren was keynote speaker at the Power of Images symposium, held on June 26 – 27, 1998, at the Center in conjunction with the exhibit Powerful Images: Portrayals of Native America. Dr. Warren has a long and distinguished career which includes serving as founding deputy director of the National Museum of the American Indian. These remarks are excerpted from his keynote address.

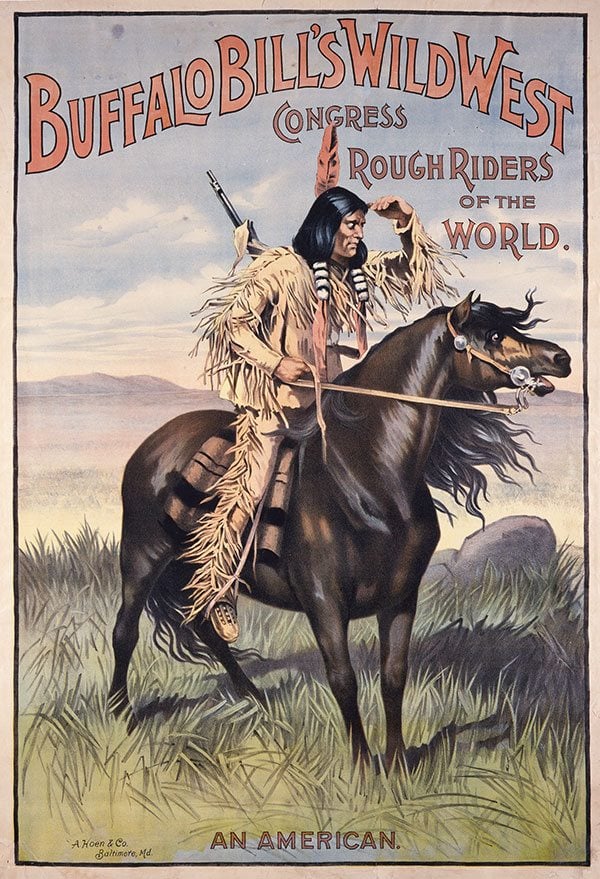

The events of the past twenty years—politically, socially, and culturally—regarding Native Americans are, without a doubt, unprecedented. Let me review a few things with you in relation to that. In the period from contact (in the 16th century) to roughly the 1960s, the unrelenting movement was to force the Native person and culture into a paradigm that was brought from another time and place. And if the Native people or culture could not fit, then they must be moved aside or eliminated. It was as simple as that.

The paradox of all paradoxes is captured in the words of Colonel Pratt, the first superintendent of Carlisle School, “Kill the Indian and save the man.” Ironically, he was one of the finest, upstanding Christian gentlemen that you would ever find with a sincere desire to help the Indian people. Educate the Indian, make him into a contributing member of American society and the problem would be resolved. The only problem was the Indian people who attended Carlisle and came home were asked much the same question as our young people when they return from universities today: “Who are you? Are you still of us or are you like them?”

The question of blood, culture, and tradition is as relevant today as it was in the 19th century but in a new context. For four to five hundred years, the process was literally one-way. In the 1880s, it was demonstrated by the Dawes Act that broke up tribal lands and sent children off to federal schools. In the 1950s, under the Eisenhower administration, an effort was made to relocate Indians away from reservations to cities, accompanied by a termination of federal trust responsibility to the tribes. The notion that culture, language, tradition, family, or land is critical to the existence of Indian people came about only in the 1920s, culminating under John Collier in the 1930s, with the formulation of a federal policy that at least recognized these factors as an alternative to the otherwise elimination of tribe and culture. A major hallmark and shift in the paradigm occurred in 1975 when President Nixon declared the self-determination policy, stating that tribal government should be recognized and given the authority to design its own future. These are important because they mark a reversal of longstanding policy.

Cultural self-determination came along with unannounced subtlety and significance. In the 1960s, the first acts which required Indian consultation on the disposition of lands of historic and cultural significance were passed. With the 1980s came the passage of the same legislation that established the National Museum of the American Indian. The Native American Graves and Repatriation Act, regarding protection of grave goods and ceremonial materials, required the repatriation of those materials to appropriately identified owners. Along with that came the American Indian Freedom of Religion Act. These are unprecedented in the history of Indian/non-Indian relations. They recognized for the first time cultural patrimony, whether it be one’s ancestral remains or materials that had been collected in an earlier era by scientists. These were finally recognized as the personal, the spiritual, and the human rights concerns of Indian peoples.

The basis for a new Indian society is being laid right now. I don’t know what that society will be except that it will be totally different from anything I ever thought could be. In it is a strong ceremonial, traditional core. It is manifested in the requirement to define and then defend what is Indian traditionalism in its ceremonial and religious cultural terms I have heard Indian people tell senators in testimony (looking at American Indian religious freedom) about the meaning of places and spaces, not in romantic ways, but rather as the basis for what constitutes our way of life and government. It is because of the empowerment chat comes from those places that our priesthood is able to conduct the affairs of our society. Without chat power, or any disruption of that power, we will then be nothing.

We have set in motion an internal process of revitalization in the Indian world that has unbounded possibilities. Ceremonies are returning after two generations of lying dormant. Language is coming back because it is imperative to a viable future. Language is the means of communication between our generations and the means of perpetuation of our ceremonial and spiritual life. What this has to do with the production of new images by and about Native Americans is part of the 21st century.

Post 118