Exhibition Explores Photos by Artist James Bama – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall 2023

Exhibition Explores Photos by Artist: James Bama – Portraits of the West

By Susan Floyd Barnett

Are westerners different from people on the East Coast? What are their defining stories? How do they express their identities through dress, performance, and work? In what ways do they embody the realities of the American West—and carry forward its myths? When illustrator and artist James Bama moved from New York to Wyoming, he began exploring these complexities of western identities through the photographs and paintings he made of his new friends and neighbors.

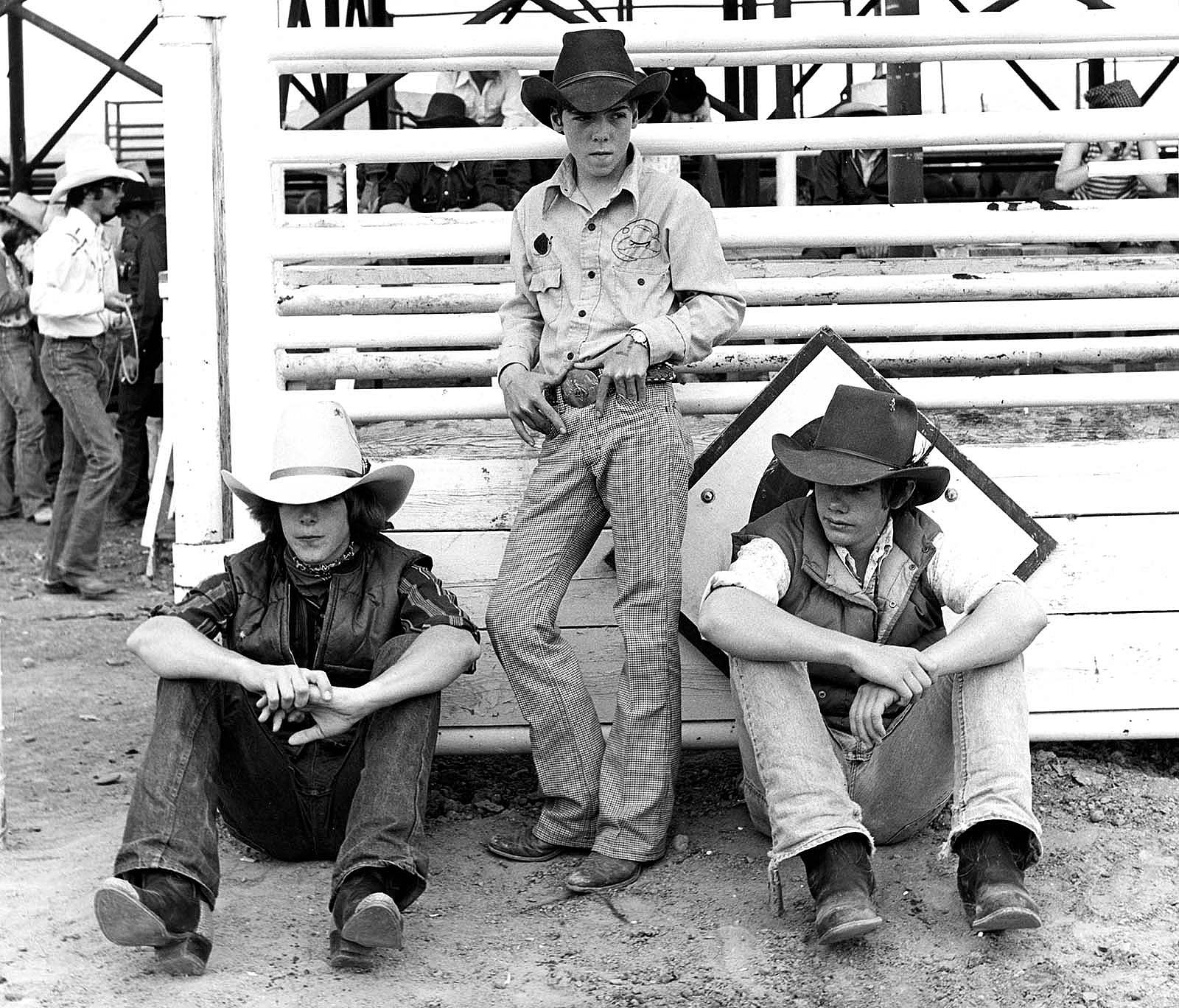

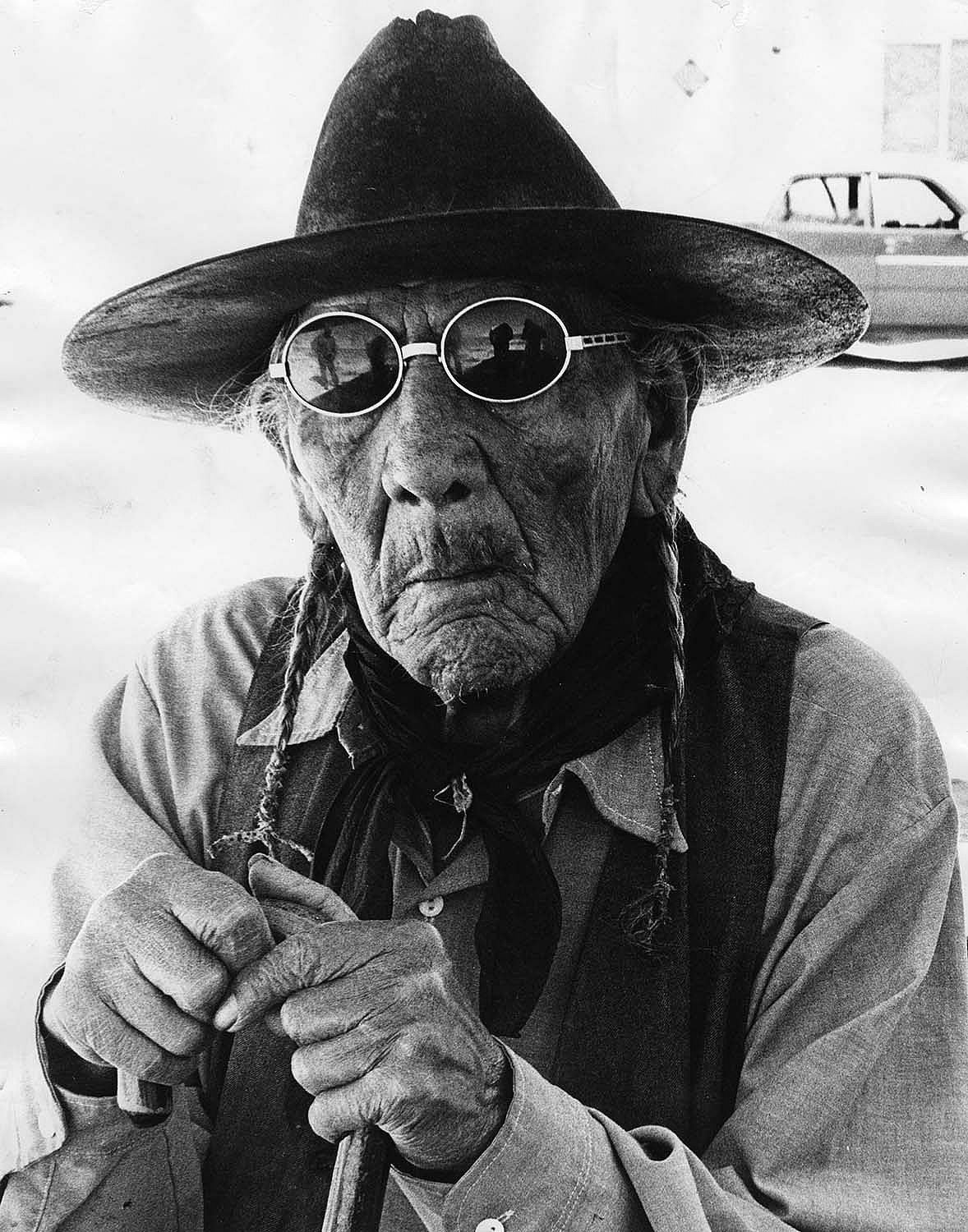

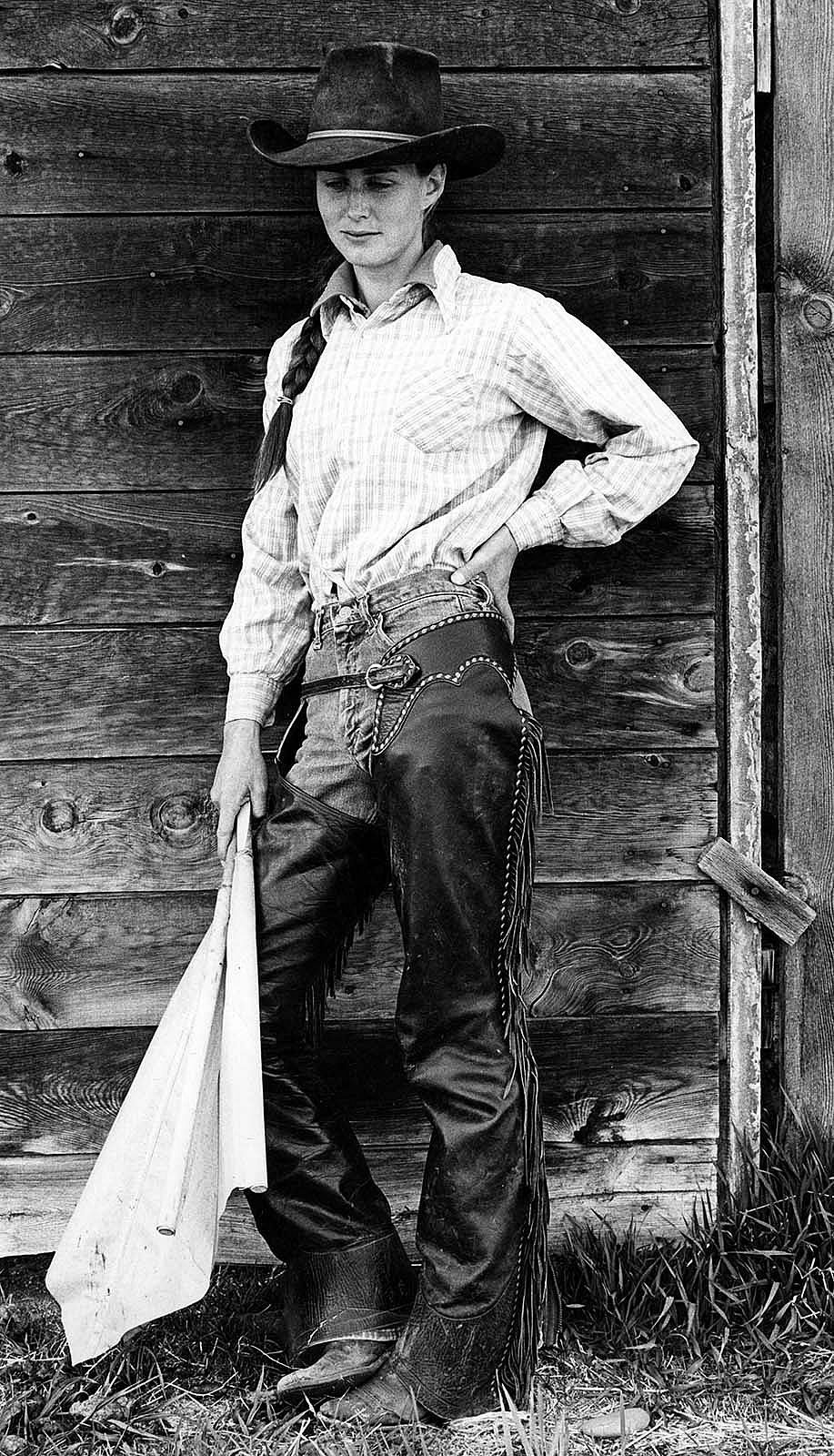

Although Bama (1926–2022) was best known for his highly detailed and realistic illustrations and paintings, photographs were the foundation of his imagery. A special exhibition opening this month offers fresh perspectives on representations of western identities in Bama’s photographic portraits. The exhibition touches on ideas such as resilience and the transfer of traditions across generations through the use of clothing, adornment, props, and backgrounds, as well as the relationship between the artist and his subjects.

James Bama’s Photographs: Portraits of the West opened October 21 in the John Bunker Sands Photography Gallery at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. A parallel exhibition opens November 13 at the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming in Laramie. Both institutions are jointly curating the showcases, featuring more than 150 distinct images in the paired presentations. Each exhibit fills in the details of their visual exposition differently, weaving together a thematic framework with distinctive selections.

At the height of his celebrated career as one of America’s premier illustrators, Bama moved to Wyoming in 1968 and began re-inventing himself as an artist. Within a few years, he achieved national recognition for his hyper-realistic paintings of westerners, especially old-timers, cowboys, and Indigenous peoples.

As part of his artistic process, Bama made thousands of black-and-white photographic portraits, which served as references for his art. Although Bama viewed his photographs as studies, they constitute insightful and compelling works on their own.

Those portraits reveal Bama’s sharp eye for composition, detail, and context, as well as the comfort and trust he earned from his models. They retain dissonances between historical trappings and the modern world, highlighting the complexity of western histories and identities. The portraits look deeply into the people on the other side of the camera, conveying a sense of the models’ humor, drama, beauty, strength, and contradictions. They also tap into a uniquely western mix of storytelling, self-representation, history, and contemporaneity.

“Many of us who live in the modern, rural West see ourselves in light of the West’s past,” said Paul Flesher, director of the American Heritage Center and curator of its exhibit, “whether that is a continuation of the lifeways from previous centuries, reenactments of events and culture from those times, or simply drawing inspiration from them. Bama’s photographs—like his paintings—capture that connection.”

Photos, Conversations, and Friendships

Soon after moving to Wyoming, Bama began learning more about the West, making friends, and getting to know the local characters through the lens of his camera. Conversations with strangers often led to photo sessions, followed by paintings, friendships, and introductions to future models.

Using a Hasselblad camera, he shot one or two rolls of film with each subject, experimenting with different poses, clothing, and props. His wife Lynne (a writer and photographer) printed the negatives onto contact sheets, which Bama reviewed and cropped using a red grease pencil. Lynne then printed his selections as 4×5-inch images, enlarging the best to 11×14 inches.

Photos were the first step in Bama’s work process. He worked with his subjects to try various poses, clothing, accessories, backgrounds, props, and compositions—sometimes in a single session, sometimes over many years.

After selecting an image to paint, Bama sketched out the composition on tissue paper, and then painted small color studies. He then used a projector to transfer a rough outline of the composition to a rigid art panel. He worked with an 11×14-inch photograph beside his painting easel, usually with a duplicate 4×5 taped in the upper corner, so he could see together the big picture and the details. To illuminate his work process, the exhibition includes a sample of Bama’s contact sheets, tissue sketches, color studies, and finished paintings.

Bama’s central interest was people and their stories, and the American West was integral to his art. However, it was not so much the historical or mythic West that engaged him, as it was the rugged faces of centenarians, the larger-than-life western characters, and the pageantry of public performances. He took hundreds of photos at Wild West show reenactments, rodeos, powwows, and rendezvous. In a 1976 interview with former Center of the West executive director Peter H. Hassrick (1941–2019), Bama explained: “I use the West…to say what I want about life. There are tremendous virtues: the older people, the hardships they endured, and the whole settling of the West, which is really a heroic saga.”

Through his photographs, Bama studied dramatic moments in the lives of ordinary people. “I would love to do knights and Vikings, the texture of the clothes they wore, the shapes and the images. But I live in the wrong period. I live in the West and plan to remain here the rest of my life, so Western people are my subject matter whether contemporary or period… I have grown into my subject matter… into mountain men and Indians, trappers, and cowboys. They are what I see, so they are what I paint.”

“There is a story in every one of these paintings because these are real people… today’s people,” he said.

A Dozen Lifetimes

The slow process of making detailed, realistic paintings (about one per month) allowed Bama to remove or exchange contextual elements to tell the stories that interested him. It would have taken more than a dozen lifetimes to realize his best photographs as paintings.

Bama told Hassrick that he already had “about four or five hundred of these [studies from the photographs] in various stages of things that I could just sit down and paint until my dying day.”

Lynne Bama stopped printing her husband’s photographs when their son was born in 1977. Bama then hired a darkroom assistant and continued making photographic portraits and shooting on location whenever there was an irresistible opportunity.

Seen together, Bama’s spectacular images tell a rich story of continuity and tradition, pageantry and performance of the American West. Like other accomplished portrait artists, Bama gave his models freedom to perform their identities. “My fantasy,” he said, “has always been to paint people living out their fantasies.”

In 2019, at the age of 93, after Bama’s eyesight began failing and he was no longer painting, he told Points West that he didn’t really mind these losses. “I’m not frustrated. Everything ends. Since kindergarten, I was copying the comic strips, Flash Gordon and Tarzan. Everything ends and I’ve had two successful, great careers,” he said.

Bama left behind a sprawling collection of materials that informed his work, donating to the Center approximately 50,000 negatives, 4,200 contact sheets, 2,000 photographic prints, and 2,500 drawings. Center employees have scanned roughly 300 of the photographs and entered 75 notebooks into its collections database.

There also are 94 paintings, ranging from small color studies to a few large watercolors, and four fully realized oil paintings. More than forty boxes of archival records include correspondence, research articles, photographs, negatives, gallery catalogs, and the artist’s published illustrations.

This amazing archive can be accessed online through the McCracken Research library.

James Bama’s Photographs: Portraits of the West runs October 21, 2023–August 4, 2024, in Cody, Wyoming and November 13, 2023–April 10, 2024, in Laramie, Wyoming.

To explore more of James Bama’s photos online, visit the collection in our McCracken Research Library’s online database.

To explore our Bloomberg Connects digital guide, point your smartphone’s camera at this QR code!

About the author

Susan Barnett is the Margaret and Dick Scarlett Curator of Western American Art for the Whitney Western Art Museum. She was previously curator for the Yellowstone Art Museum and has also worked as a gallery owner. Her career has focused on contemporary art, including photography and the art of the American West.

Paul Flesher contributed to this article.

Post 349

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.