For the average nature enthusiast, a love of the wild world starts at an early age and grows into adulthood. For James Prosek, that childhood love of nature catalyzed his illustrious, multi-faceted career as an artist, writer, and naturalist—and brought his world-renowned work to the Center of the West.

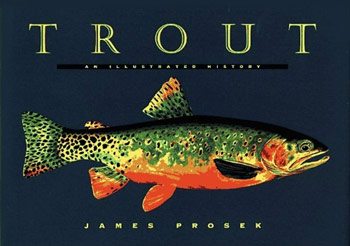

You briefly mentioned that trout have been an “obsession” of yours from a very early age. How did that obsession begin, and how did it translate to Trout: An Illustrated History?

My father introduced me to nature through his love of birds… I painted birds first copying the works of John James Audubon and Louis Agassiz Fuertes and later, Winslow Homer. I came to a love of nature through art and drawing. Drawing and painting in watercolors helped me observe the world in a new way. When I was nine years old a friend of mine at school introduced me to fishing in the ponds, reservoirs and streams near our homes in Easton, CT. Around the age of ten I caught my first native brook trout in a stream entering the north side of the Easton Reservoir. That fish changed my life. I couldn’t believe that a creature so colorful lived in the streams near my home. I fell in love with trout and went to the local library looking for a book on the trout of North America. I couldn’t find one so I set out to make my own. I traveled the US as soon as I had a driver’s license, looking for native trout to paint. When I was a freshman in college I sent out ten proposals to do a book on trout and was fortunate enough to find a publisher.

While you are well-known for your art, you’ve had success in other disciplines as well, including writing and documentary work. How do you balance all of your artistic interests, and somehow, find success in all of them?

A lot of my work is a kind of critique of naming and ordering nature. Names put things into boxes and, though useful, can limit the potential of what something can be. I don’t necessarily see a boundary or divide between the different creative projects I take on—writing, painting or documentary work—although they all require a certain rigor and time to develop a skill set. I have dedicated countless hours to my writing. Writing helps to bring clarity to my own thoughts, it also exercises my brain, and I find it has become an integral part of my art making practice. But the act of writing and art-making do demand their own separate spaces (both literally and temporally!), and I’ve found it harder and harder to transition from one to the other and back again. I think it is just persistence that allows me to do these different things and the dedication of a lot of time to working. Language is one way to communicate, painting is another, film is another, music yet another. Why not try to make use of all of them!

How did you become involved in Invisible Boundaries, and how would you describe your role and purpose in the project?

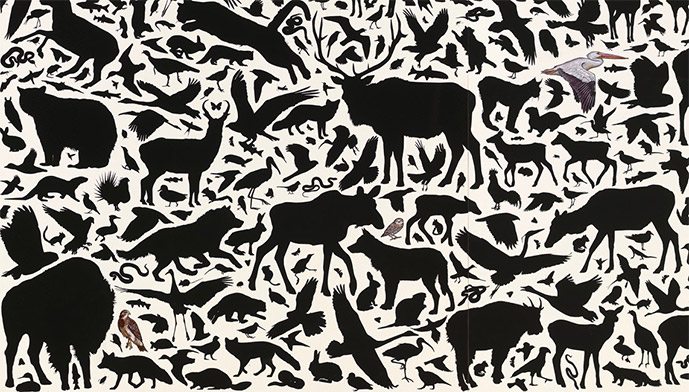

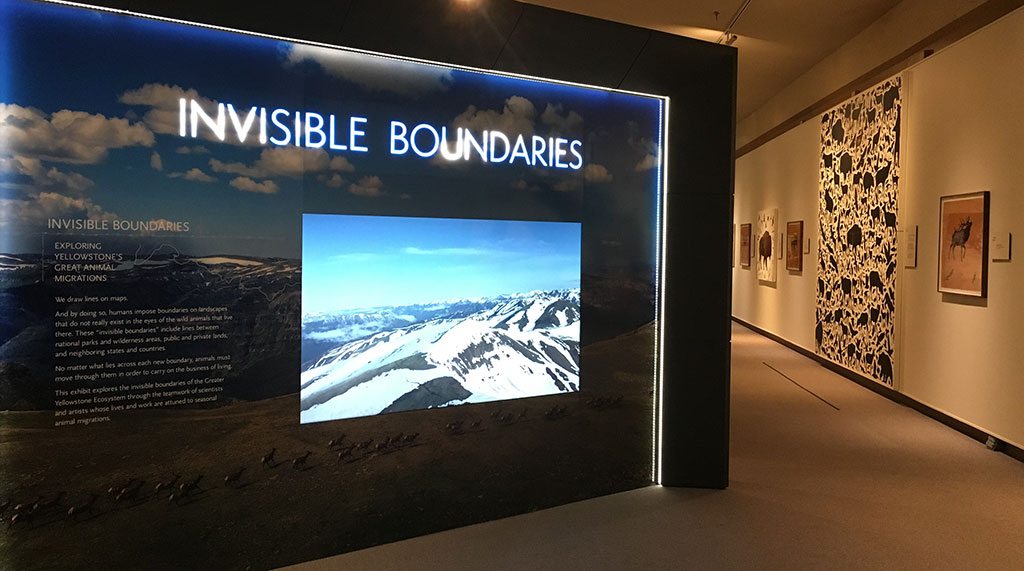

I met Arthur Middleton, our scientist in the project, when he was a graduate student at Yale. I came to give a lecture to his class and we began a correspondence. It was some years ago that he mentioned that he’d won a fellowship (Camp Monaco Prize) to do an exhibition on migration at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. We shared an interest in boundaries that humans draw between things in nature, whether they are the lines we create between things in order to fragment nature and name it, or lines on maps, like the border of Yellowstone which has real world consequences for any animals that attempt to cross it. The exhibition we envisioned would address the boundaries humans impose on nature that affect their movements and migrations, but it would also nod at the fact that we were breaking disciplinary boundaries by collaborating with each other. With Joe Riis we covered the disciplines of ecology, photography, and painting. My role is as the artist, making interpretations of concepts that may not be as easy with the language of science or photography.

Artists and scientists have combined forces to better understand our world for centuries. What was it like being on a team like this, and more specifically, what was it like collaborating with the likes of Joe Riis and Arthur Middleton?

It was a lot of fun, I loved working on this exhibition.

I have always loved Yellowstone since I first visited with my family when I was four years old. So having an excuse to work in the backcountry there was a huge bonus. I had multiple purposes for being involved. One was to make and exhibit art. Another was to do research for a chapter on Yellowstone for a book I’m writing on how and why we name and order nature. The collaboration was challenging at times because three people with different priorities are sharing a space and telling a story together, but it was a very valuable and enriching collaboration in my mind.

What is it, in your opinion, that makes art and science such a compelling combination?

Well science needs to deal in tractable data collected in the field or wherever. It needs to be precise and controlled and methodical and tested over and over. You can’t just make conclusions based on intuition and experience. Art on the other hand, one could argue, is all about ones intuitions and expressions of personal experience, examination of the soul… So put them together and you have a more full and fulfilling story of anything, the result is closer to what it means to be human.

See Prosek’s work in Invisible Boundaries at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West until January 17, 2017.