Originally published in Points West magazine in Winter 2008

Yellowstone and Jellystone:

Yogi Bear at 50

By John Rumm, PhD

Former Curator, Buffalo Bill Museum

He’s not only “smarter than your average bear”—he’s a whole lot older, too. October 2, 2008, marked the fiftieth birthday of one of America’s most beloved bruins—Yogi Bear, the wisecracking, tie-wearing, rule-breaking denizen of “Jellystone National Park.” His birthday provides an opportunity to consider how this cartoon character helped color people’s views about bears, national parks, and even nature itself.

In 1872, the United States Congress passed legislation creating the world’s first national park—Yellowstone. Tourists began arriving—on horseback, by stagecoach, and, by 1915, motor vehicle.

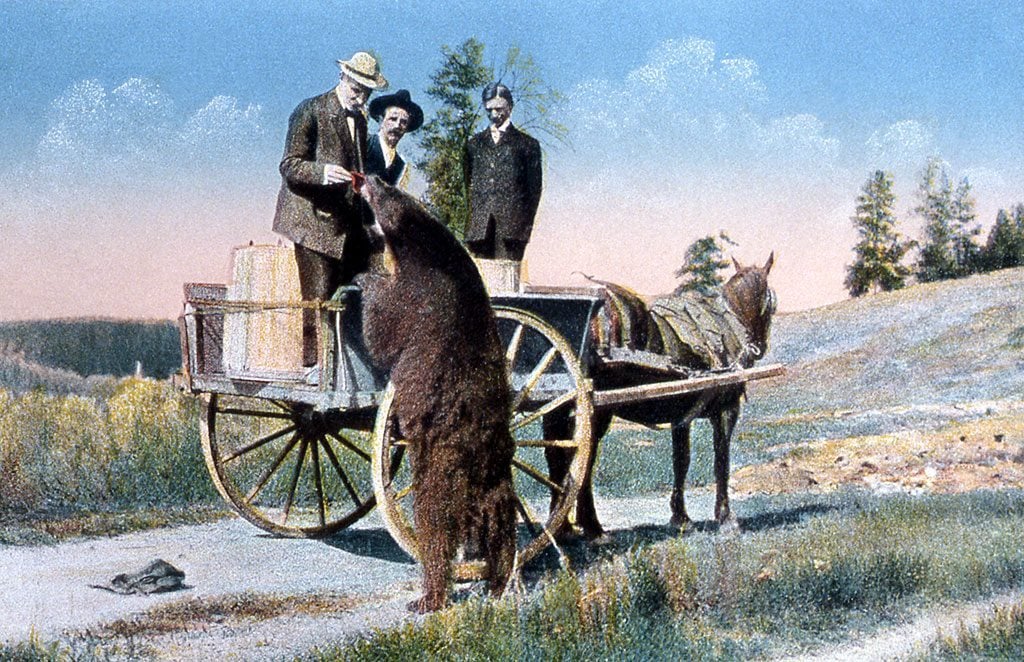

Now, bears are intelligent and adaptable. They soon realized that where people were, so was food. Plus, though ostensibly smarter than bears, people engaged in foolish and dangerous behavior—offering bears treats, taunting them, even coaxing them to pose for photographs. In 1902, Yellowstone officially banned “the custom of feeding bears on the part of tourists [and] employees.” But, the ban was largely ignored, with predictable results. In 1916, the park reported its first fatal bear attack, and dozens of people were being hurt annually.

To discourage tourists from feeding bears, Yellowstone authorities created “bear pits” into which “bear keepers” dumped leftover food. The nightly bear-pit feedings became so popular that grandstands were erected, seating several hundred spectators.

Popular culture helped reinforce the idea that bears were like people, only fuzzier. The “teddy bear craze” of the early 1900s fed a desire for soft and cuddly bears. So did

“Winnie-the-Pooh,” the lovable bear whose tales captured readers’ hearts worldwide.

Yellowstone’s bears, for their part, were fast losing their fear of people. They roamed freely through the park looking for food—upending trash cans, ravishing campsites, and begging handouts from motorists. “Bears are no longer wild animals,” a National Park Service official observed in 1928. “They have become personified. They are like people, and the visitors to the park want to treat them as such.” They came loaded for bear hugs, if not for bear.

By the 1950s, what historian Paul Schullery has termed the “Era of the Great Yellowstone Bear Show,” was in full swing. A postwar boom in leisure travel caused Yellowstone’s annual visitation to soar, reaching 1 .5 million by 1955. In addition, though a 1953 survey showed that fully 95 percent of respondents knew they shouldn’t feed bears, many still did. After all, how could one resist when a “poor hungry bear” looked wide-eyed at you?

The situation was hampered by the equivocal attitude of park authorities. Rangers told visitors not to feed bears, but rarely fined them if they did. ln 1957, a Yellowstone flyer warned that. “Park bears are wild animals,” and advised visitors to close their car windows if bears approached. However, its photograph showing three bear cubs standing upright and peering into a station wagon was more like an invitation to a photo-op. Nor did it help that Yellowstone’s senior naturalist, admitting his view might be “heresy,” expressed hope that “the time will never come when there are no bears sitting by the roadside awaiting a handout or in the campgrounds taking advantage of the careless camper.”

If people loved seeing moocher bears, it was but a short creative leap to imagine bears acting like people. That idea occurred to William Hanna and Joe Barbera. They had spent twenty years at MGM Studios, producing the popular “Tom and Jerry” cartoons. In 1956, MGM abandoned the animation business, and Hanna and Barbera formed their own company to develop half-hour-long TV shows featuring cartoon animals. In 1957, working for Screen Gems, they produced “Ruff and Reddy,” about a cat and dog. A year later, in October 1958, they premiered “The Huckleberry Hound Show,” with three segments featuring the eponymous canine sheriff; “Mr. Jinx,” a cat tormented by two mice; and an amiable ursine, “Yogi Bear.” It became America’s top-rated show.

Yogi Bear was novel yet familiar. His creators modeled him after “Ed Norton,” the character that Art Carney immortalized in television’s “Honeymooners”—right down to Norton’s hat, slouch, and mannerisms. Yogi’s face resembled that of Yogi Berra, the Yankees catcher beloved for uttering “Yogisms” such as “It ain’t over, till it’s over.” Yogi Bear had his own catch-phrases—”Hey, hey, hey” among them—and, besides being “smarter than the average bear,” was also much more “human.” He talked, walked erect, golfed, and drove a car. He even had five-fingered hands instead of paws.

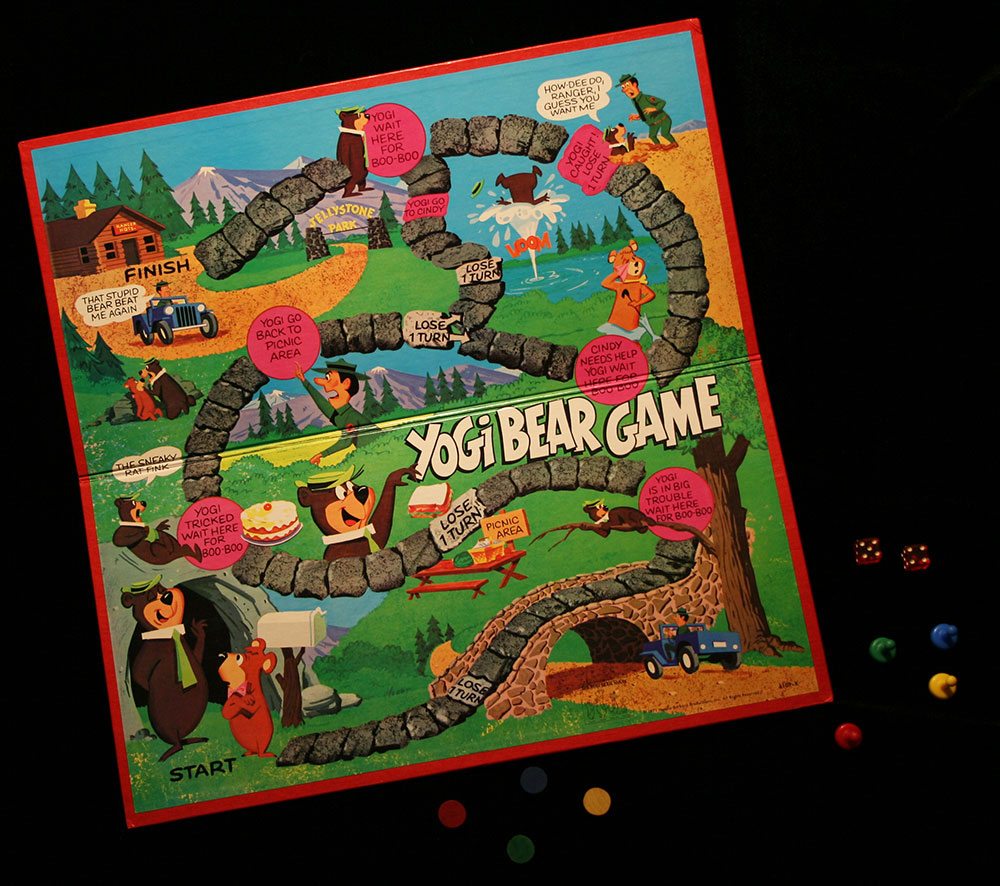

In his cartoons, Yogi was forever scheming to steal “pic-a-nic baskets” from unwitting Jellystone campers, much to the chagrin of his adorable companion, “Boo Boo Bear.” Yogi’s friendly nemesis was Park Ranger Smith, whose sole job, apparently, was to keep Yogi out of trouble.

“Jellystone” obviously was inspired by Yellowstone, but they were worlds apart. Both offered mountains, forests, waterfalls, and geysers. Yet, while Yellowstone epitomized “wild nature,” Jellystone was orderly and predictable. It was nearly always sunny there. You never saw forest fires or blizzards. Nor, for that matter, did you ever see wild animals—no bison, no elk, not even butterflies. As for people, Jellystone seemed deserted for a national park. The few people Yogi encountered were nincompoops, or at least easily duped. And, of course, you never, ever saw Yogi or Boo Boo physically harm a human. Their escapades were always harmless. Even the hapless campers whose picnic baskets Yogi swiped never went hungry.

Yogi proved so popular that, in February 1961, in the first TV “spin-off,” he gained his own show. Within a year, it was airing on nearly two hundred television stations nationwide, as well as in Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan. In 1964, Yogi and his pals “left” Jellystone for Hollywood to star in a feature-length film, “Hey There, It’s Yogi Bear.” While production of the TV show ended, it was (and still is) shown in re-runs, and millions of readers followed Yogi in comic strips and storybooks.

For the National Park Service, Yogi’s appeal was a mixed blessing. He helped boost visitation—not just to Yellowstone, but nearly all parks. But so many visitors asked Yellowstone’s rangers about Yogi, that it seemed many believed he really lived there. In the summer of 1961, two park service representatives traveled around Europe in a chartered bus to promote U.S. tourism. Everywhere they went, children inquired, “How is Yogi Bear? How are things in Jellystone Park?”

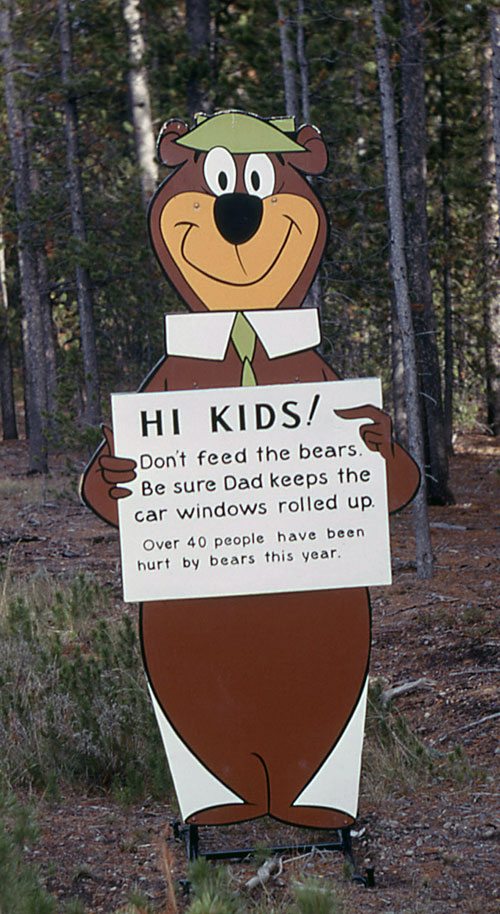

Eager to leverage Yogi’s popularity, Yellowstone authorities enlisted him in their anti-bear-feeding efforts. He appeared in a flyer warning that “Yellowstone Park Bears Are Dangerous,” but it showed Yogi clutching a picnic basket and eating a sandwich. Likewise, life-sized cutouts of Yogi holding a “Don’t Feed the Bears” sign appeared throughout the park. In his cartoons, however, Yogi scrawled the words “Except Yogi” beneath the sign—thereby undercutting the message. Data on annual incidences of bear-related injuries at Yellowstone suggest that Yogi’s image adversely affected visitors’ perceptions of bears. From 1957 to 1959, the number of annual injuries from bear attacks fell from 74 to 37. But in 1960, the number spiked, rising to 69 injuries. A park service administrator concluded that humorous roadside signs and flyers, such as those featuring Yogi, had “instill[ed] a sense of levity rather than one of seriousness in the visitor.” Stung by such criticism, Yellowstone authorities discontinued using Yogi’s image.

It was a tragic event, though, at another national park that lineally ended the “Yogi Bear era” at Yellowstone. On the night of August 19, 1967, grizzlies mauled to death two 19-year-old women who were camping in Glacier National Park’s backcountry. Public outcry led Congress to begin investigating the park service. In response, Yellowstone and other parks adopted a new bear management policy in which they closed the “bear pits,” imposed stiff penalties for feeding bears, and actively began studying bear ecology.

Yellowstone may have ended its association with Yogi, but “Jellystone” lived on. In 1968, a group of Wisconsin investors formed “Jellystone Campgrounds Limited,” licensed the characters from “The Yogi Bear Show,” and began franchising “family recreation parks.” Now operated by Leisure Systems, Incorporated, the Jellystone Park Camp-Resort network is composed of some seventy sites in the U.S. and Canada. Just as Yogi is not your “average bear,” Jellystone Parks are not your average campgrounds. Along with campsites and hook-ups for recreational vehicles, the parks offer heated swimming pools, supermarkets, restaurants, beauty salons, miniature golf, pedal-carts, video arcades, wi-fi service, and amusement rides. If you want to commune with nature, you can watch “Old Faceful Geyser” erupt twice daily.

At each Jellystone Park, you can also visit Ranger Smith’s Office, Yogi’s Cartoon Theater, or Boo Boo’s Souvenir Stand. Yogi and his pals make daily appearances, driving golf carts, playing games, posing for photos, and even picnicking with campers (without stealing their lunches). You can even join Yogi on an evening “Hey Hey Hay Ride.”

By the mid-1970s, many Jellystone Camp Resorts sold building lots. Mobile homes and cottages soon appeared, along with storage sheds, patios, decks, wet bars, gazebos, and hot tubs. Some residents even replaced their lawns with Astro-Turf, replete with ceramic squirrels and plastic pink flamingoes.

In short, Jellystone Camp Parks came to resemble the cartoon Jellystone: well-ordered, safe, and predictable—veritable “peaceable kingdoms” where bears act like real people. No wild animals there! Nor unruly humans, either. As a company spokesman told a Chicago Tribune reporter in 1985, “We control our element out here. If someone…doesn’t [act] like they belong here, we have the option of saying ‘No.”‘

Jellystone promoted its parks as the best way for families to enjoy “the camping life” together. As a company spokesman told the Tribune, public parks like Yellowstone “are great for getting away from it all: pitching your tent, opening your six-pack. But if you have children 2 to 6, you’re there for an hour and it’s ‘Mom, what are we going to do now? I’m bored.”‘

What was billed as the “ultimate” Jellystone Park Camp-Resort opened in 1973 in Oak Glen, near Yucaipa, California, two hours from Los Angeles. Along with the usual amenities, it featured a cocktail lounge, a wine and cheese shop, and “Yogi’s Cave,” a discotheque for teens. It shared a parking lot with “Oak Glen Village,” an upscale shopping center offering boutiques, antiques, and art galleries. An indoor mall was only a block away.

Art often imitates life, and in 1991, Yogi returned to television in a new half-hour show, “Yo, Yogi.” Reflecting producers’ desire to offer a hipper, more “urban” ursine, Yogi and Boo Boo, now 14 and 8, wore sunglasses, flashy shirts and sneakers, rode skateboards, and hung out with their friends at Jellystone Mall, just down the road from the park. They no longer filched picnic baskets, but instead helped “Officer Smith,” of Jellystone’s Lost and Found, recover lost wallets, re-unite parents with missing kids, and keep the mall secure.

The irony of this was not lost upon the National Park Service. An agency spokesman told the Wall Street Journal that he “worries[d] about the message sent to TV viewers when the ‘smarter than average’ bear leaves a park for a mall.”

“Yo, Yogi” was cancelled after one season, perhaps because viewers agreed with the park service that Yogi belonged outdoors. Yet, even as Yogi turns the big Five-O, Yellowstone and other national parks are facing growing pressure to become more like “Jellystone” themselves, by people wanting wi-fi access, fast food restaurants, arcades, and even golf courses. How long before “Yellowstone Mall” opens nearby?

Interviewed in 1985 by the Chicago Tribune, a corporate representative described how “city folk” enjoyed visiting Jellystone Camp-Resorts. “I’d walk by [the campsites],” he mused, “and some guy would be lying out in his lawn chair, having a beer. And you know what he’d be saying? ‘This is really getting away from it all. Yessir, this is the life.'” But, the spokesman also noted that “I’ve had people come up to me in the morning and say ‘There were bears in my garbage can last night. I’m not kidding, I saw a bear.’ And I ask them, ‘Was his name Yogi? No, what you saw are called raccoons.'”

More than a century ago, people started coming to Yellowstone to see the bears, who wound up feasting on garbage and becoming habituated to humans. Now, when they visit Jellystone Park, some people no longer recognize real bears.

As we celebrate Yogi’s 50th, perhaps this should give us all paws.

Post 161