Girls Gone Wild West

Decades before the famous—or infamous—videos began appearing showing Bad Girls Being Naughty, another bevy of beauties became known worldwide for their exploits.

They were classy, brassy, sassy, and sexy to boot.

They were fun-lovin’, hard-drinkin’, and—at least some of them—hard-lovin’, into the bargain.

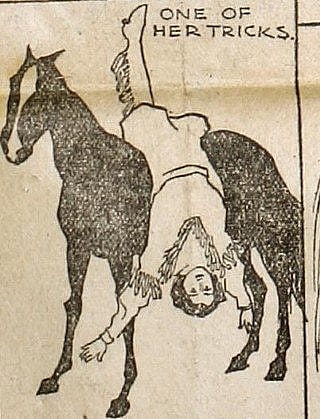

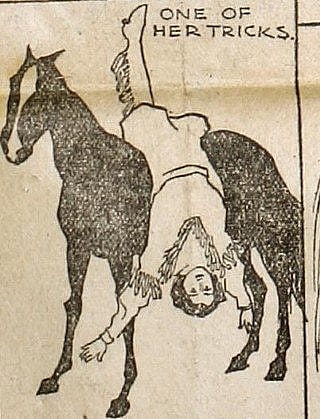

They were sharpshooters and trick ropers, acrobats on horseback, and champion bronco-riders.

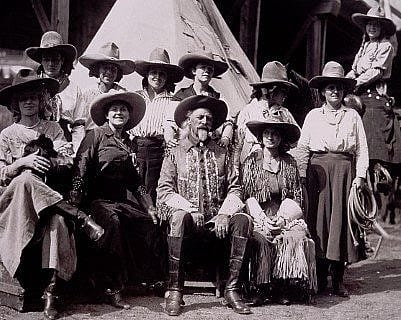

They were the legendary cowgirls of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West.

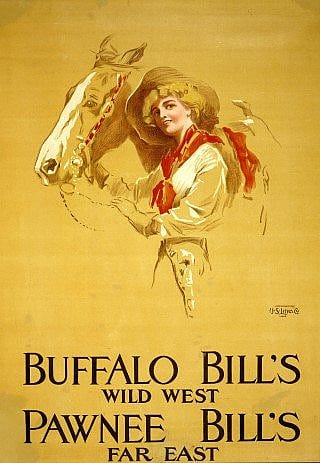

No slouch when it came to publicity, William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody appreciated, and capitalized upon, the charms and attractions of the women who performed in his Wild West show. He featured them in posters and promoted them in advertisements. For example, a 1907 “Courier”—a prospectus for the coming season—touted the Wild West’s cowgirls as “strikingly graceful representations of physical and equestrian beauty.”

Drumming Up Business and Turning Heads

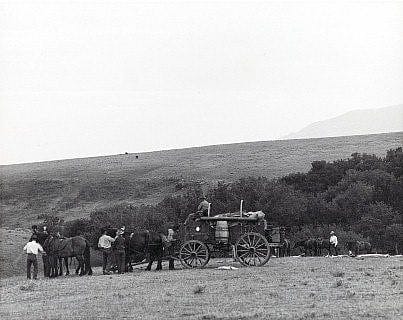

Whenever the Wild West stayed in one town for a few days, Cody sent his cowgirls into local shops, hotels, saloons and other establishments, looking to drum up business and turn more than a few heads in the process.

And newspapers couldn’t get enough of them.

They loved it, for instance, when Goldie Griffith—whom one Wild West cowboy fondly remembered as “the gol darndest gal who ever sat leather”—rode her horse up the steps of Grant’s Tomb one day when the show was in New York City.

Or the time—also in New York—when Minnie Thompson–whom one paper described as ‘a slim young woman in a well-fitting khaki suit”—unhitched a horse from a carriage, tossed a side-saddle on its back, and staged an impromptu performance of equestrian acrobatics before hundreds of astonished onlookers in Central Park.

Or when Nan “Two Gun” Aspinwall, on a bet from Cody that she couldn’t do it, rode her horse 3,000 miles across the country, from San Francisco to New York.

Romancing the Wild West Women

But when it came to affairs of the heart involving Wild West cowgirls, the papers really ate it up.

They eagerly reported, for example, the 1886 marriage between Lillian Smith, a Wild West sharpshooter and rival of Annie Oakley’s, and Jim “the Kid” Willoughby, a Wild West cowboy. Smith’s parents had objected to the liaison. Undeterred, Lillian and The Kid arranged to be married in a secret ceremony inside a tent in the Wild West’s camp. It proved to be the proverbial “shotgun wedding” if there ever was one, for the bride-to-be’s father was said to have been prowling the show’s grounds, gun in hand, ready to shoot the groom.

Then there was the time a young Army officer in the Wild West’s cast courted “winsome Blanche McNenny, the queen of the cowgirls,” as the New York Journal wrote early in April 1898. The paper reported how the pair met while performing—how she was drawn to the tall, handsome, yet shy sergeant, he to the splendid horsewoman whose “figure sway[ed] like a reed under a blowing wind.”

“I do so admire soldiers,” Miss McNenny declared. But the sergeant’s intent to bestow his affection upon her took a backseat to the prospect of joining the cause should the United States and Spain go to war over Cuba. By late April—unhappily for Miss McNenny—that event had come about; the young officer left her, and the Wild West, behind.

Which only goes to show, you winsome, you lose some….

Breaking Broncs and Hearts

But when it came to romance, few Wild West cowgirls outmatched Annie Shafer (sometimes spelled “Schafer” or “Schaeffer”). Born in Arkansas around 1885, she started riding bucking steers on her father’s ranch before she could walk, and broke her first bucking horse at the age of 14. She joined the Wild West in 1907 and was billed as “the only female bucking pony-rider of the world.” In April of that year, when the Wild West performed in New York’s Madison Square Garden, a female reporter for the New York Evening World saw Shafer ride and figured “that a twenty-two-year-old girl who knew so much about managing wild horses might have something interesting to say about managing men.” She visited the Wild West’s camp and interviewed Shafer, asking her “to tell me all she knew of the ungentle art of breaking broncos, and the gentle art of breaking hearts.”

“To manage a buckin’ horse,” said the cowgirl, “you’ve got to make him believe that you’re his master. To manage a man, you’ve got to make him believe he’s yours.”

Warming to her topic, Shafer explained the difference between “cow ponies”—horses that were agile, yet tame in the saddle—and bucking broncs. “Managin’ a buckin’ horse is a matter of mind and nerve,” she confided. “One day you think you’ve got ’em trained to eat out of your hand, the next they look at you as if they’d never seen a bridle before. Some of ’em are natural born ‘outlaws’—that’s what you call a buckin’ horse you can’t do anything with. We just leave ’em out in the field and catch one now and then when we want to have fun with ’em.”

“And men?” the reporter pressed her.

“I’ve never seen the buckin’ horse I couldn’t manage, and I’ve never seen the man I could,” replied the world’s only lady bronco-buster. “Some men are like cow ponies—too tame to be interestin.’ Some are buckin’ broncs you can’t be sure of for a minute. I don’t know if I could manage a buckin’ man. And I guess the rest are just ‘outlaws.’ But I like ’em just the same!”

Annie Shafer, Minnie Thompson, Goldie Griffith, and the rest—whether it came to breaking horses or hearts, the cowgirls of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West captivated audiences worldwide.

Written By

John Rumm

John C. Rumm is the former Director of the Curatorial Division and Curator of Public History at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. He did his graduate work at the University of Delaware, earning both a Master's degree and a doctorate in American History, and has spent most of his career working in museums and historical agencies. After living many years in the Midwest and East, he relocated to Wyoming in 2008 and deeply loves the American West.