Taking a deeper look: Mardon’s “The Battle of Greasy Grass”

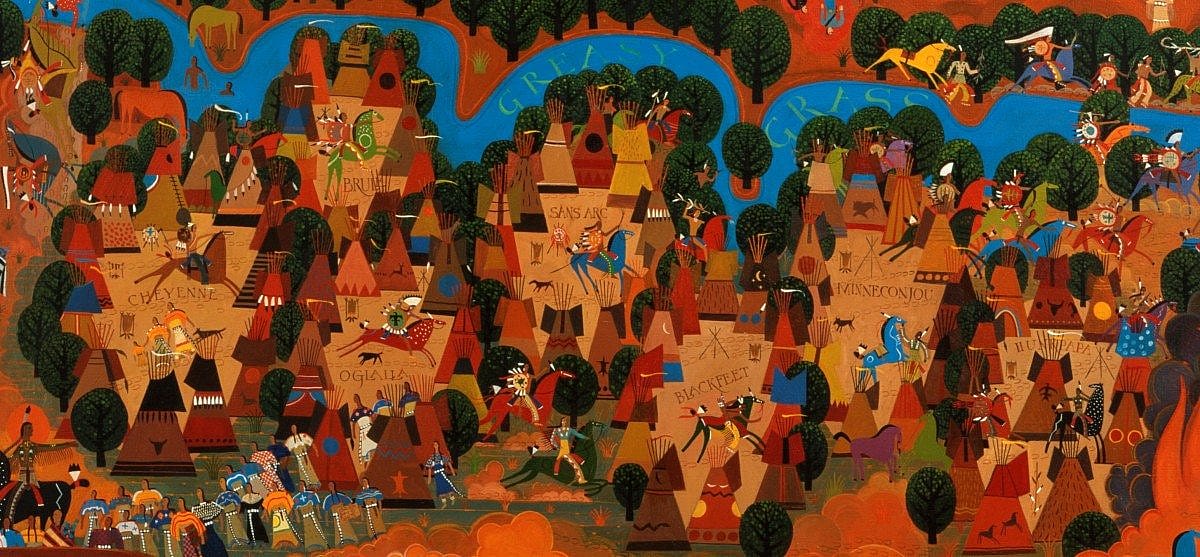

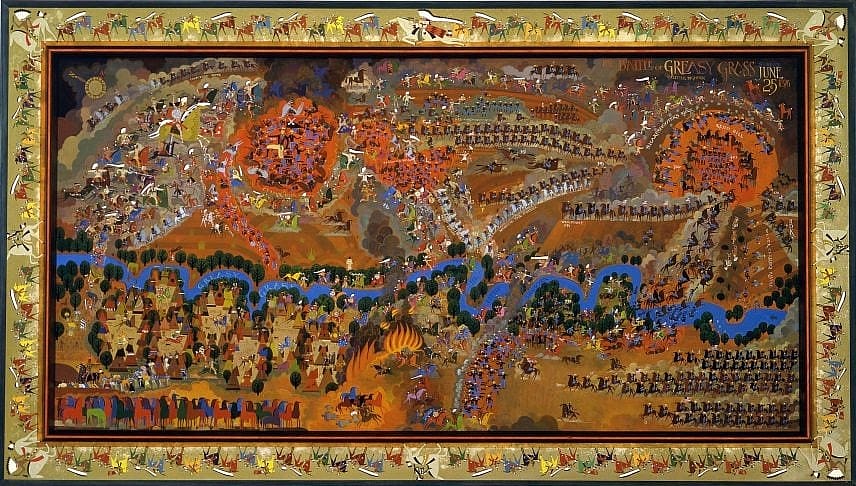

Across from Edgar S. Paxson’s Custer’s Last Stand in the Whitney hangs an equally-captivating work of color, narrative, and sheer size. Non-Native American artist Allan Mardon’s extensive study of Native American history, culture, and visual techniques confronts the ambiguity of truth about the Battle of Little Bighorn, Custer’s Last Fight, Custer’s Last Stand—whatever battle title you have—in his work The Battle of Greasy Grass.

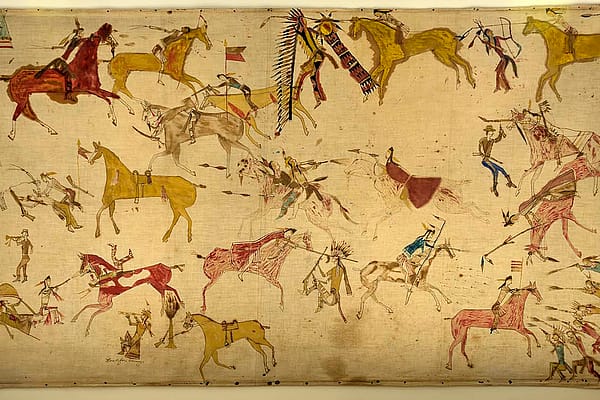

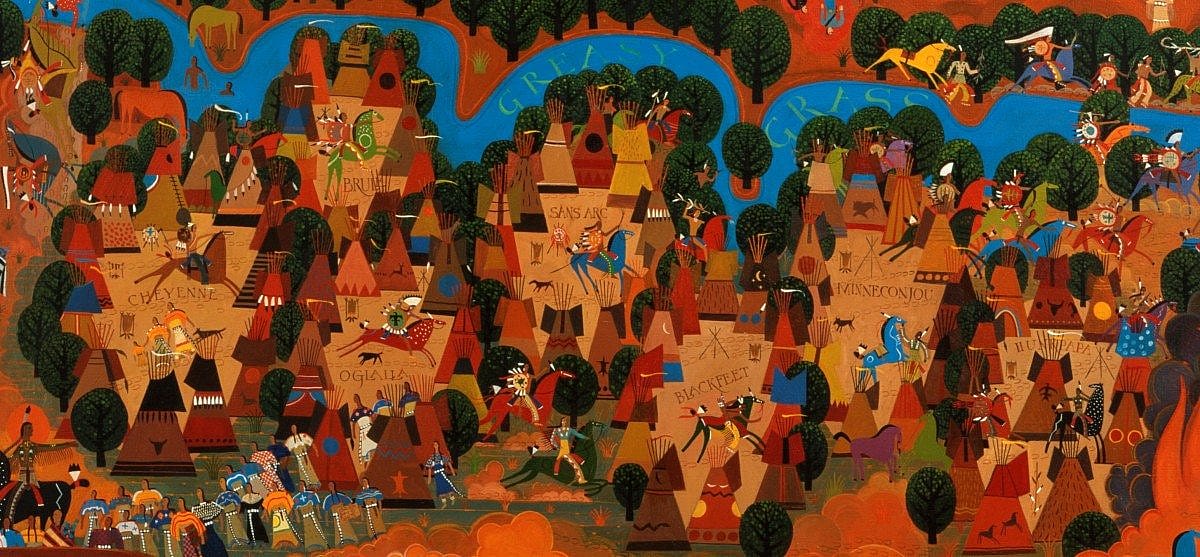

Beginning his artistic career as a commercial artist for magazines like Time and National Geographic, Allan Mardon (b. 1931) moved in 1988 from New York to Tucson, Arizona, for retirement and to pursue fine arts. In this pursuit, Mardon studies Native North American cultures and explores the “spiritual, war and social life of the Indians” through painting. Developing his unique style, his art articulates an influence of Plains Indian ledger design and Indian hide paintings.

The Battle of Greasy Grass was no simple project. Mardon’s expertise as an artist and researcher are well-communicated through The Battle of Greasy Grass. The composition of the work presents duration of time by capturing the significant moments between 3 p.m. June 25, 1876, to 3 p.m. June 26, 1876, and frames the expanse of space by reducing the ten mile battleground onto a canvas approximately six feet tall and eleven feet wide.

Mardon spent one year researching the lengthy and controversial history of the Battle of Little Bighorn, taking just as long to paint the work itself. Mardon gathered modern accounts from Native Americans, striving for historical accuracy, and formulated a contemporary composite that includes individuals unrecorded by others like Paxson—Cheyenne witness Kate Bighead, Bismark Tribune reporter Mark Kellogg, and African American scout Isaiah Dorman. Powerfully titled The Battle of Greasy Grass, Mardon reinforces the painting’s Native American perspective by employing the Lakota name for the battle, termed after the “greasy” appearance of the grass in the waters near the battle site.

While Mardon adamantly worked for historical accuracy, it is important to note that The Battle of Greasy Grass is an artistic, rather than literal, representation. Mardon’s eye-catching color highlights the influence of ledger art but also his use of artistic license. He depicts Indian ponies in non-realistic colors to differentiate them from troop horses, while trails of red tracking the path of the troops were used in place of portraying the mutilating and killing effects of weaponry.

Permanently in the Whitney’s collection since 2001, Mardon’s The Battle of Greasy Grass continues to perpetuate discussion of that monumental battle from more than one hundred years ago and serves as a didactic challenge to the historical constructs of the West. This unique illustration of the 24 hours of events in the Battle of Greasy Grass addresses the bygone misunderstandings and inaccurate disseminations of historical Native American accounts that have over time been assumed as prevailing fact.

Written By

Emily Kassebaum

Emily is the summer 2014 curatorial intern with the Whitney Western Art Museum. She hails from Seattle, WA and finds the simple, enticing charms of Cody and the region’s compelling art and history to be quite fulfilling. Having never been to Yellowstone before, Emily spends weekends exploring the US’s popular organic amusement park.