The Frederic Remington Catalogue Raisonné

Melissa J. Webster

Catalogue raisonné, a French term, literally means “reasoned catalogue”1 and is translated as descriptive catalogue. A catalogue raisonné lists and often illustrates either a particular category of an artist’s work or the entire oeuvre. The Remington catalogue raisonné includes signed oils, watercolors and drawings by the artist. It also includes any unsigned oils, watercolors and drawings that were published during his lifetime as well as certain unsigned, unfinished paintings and oil studies in the collections of the Frederic Remington Art Museum and the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. Selected unsigned studies, drawings and photographs that relate to a particular finished artwork are also depicted or referred to. The type of information listed for the objects includes, when available, curatorial data, provenance, exhibition history, bibliography, location and comments or explanations.

There are many ways to structure a catalogue raisonné. In this catalogue, the artworks are organized chronologically by year. Because the majority were originally illustrations, within each year, we have organized the artworks into two major groupings: “Not Illustrated in the Artist’s Lifetime” and “Illustrated.” The latter category is further broken down into “Illustrated in Books” and “Illustrated in Periodicals.” Books are listed chronologically and then alphabetically by title; other publications are listed chronologically and then alphabetically by title when dates are the same. If more than one article appears in the same publication, the articles follow an alphabetical arrangement. The artworks are then listed alphabetically under the appropriate bibliographic reference. Objects listed in the “Not Illustrated in the Artist’s Lifetime” category follow a strictly alphabetical sequence.

Bringing together all an artist’s wok and organizing it clarifies stylistic changes and development in an artist’s career, reveals much about his or her artistic process, helps authenticate new works that surface, substantiates old theories concerning the artist’s work and sparks new speculations. More broadly, catalogues raisonnés of American artists help illuminate and define more clearly developments in American art history.2 Museums, universities, foundations, art galleries, auction houses and independent scholars have undertaken catalogues raisonnés for numerous American artists, including Mary Cassatt, Maurice and Charles Prendergast, Thomas Moran, Alfred Jacob Miller, Winslow Homer, William Merritt Chase and Childe Hassam. 3

Each catalogues raisonné has its own starting point, often a collection of the artist’s work or of archival material of the artist. Remington was an illustrator for much of his life, so for this project, his illustrations seemed a logical place to begin. Starting with bibliographies listing Remington’s illustrations and volumes of scrapbooks depicting them, the Buffalo Bill Center of the West began the research for the Remington catalogue raisonné project in 1984.

Early scholarship in organizing Remington’s work

Over the years there have been several attempts to organize Remington’s oeuvre. Remington himself kept ledger books in which he recorded information pertaining to his artworks. For example, he listed illustration commissions, logging in the titles of illustrations or brief descriptions of the subjects to be depicted, and usually listing the periodical or book the pictures were for, the title of the article and the author. For his Collier’s Weekly contract, which called for twelve illustrations a year beginning in 1903, Remington wrote the year and projected month of publication next to each title, although the actual date a particular image was reproduced was usually later.

In these ledger books, of which there are four plus a partial listing in the front of an address book, Remington also recorded painting commissions, proposed artworks and mapped out exhibitions, writing down artworks to be shown and where. Although Remington’s ledger books are not definitive they span most of his artistic career, dating from as early as 1887 to as late as 1909. Remington went back to them over the years to update an artwork’s current standing, noting if sold, sometimes the buyers name and the price, if exhibited or in storage or even destroyed or repainted, and crossing out earlier information. Some artworks have several notations scribbled and crossed out; the entries next to The Prowler, for example, read, “Verhoff [sic] 700 O’Brien 800 (all crossed out) Destroyed by self.”4 (Verrhoff and O’Brien, the former in Washington, D.C. and the latter in Chicago, were art dealers who handled Remington’s art.)

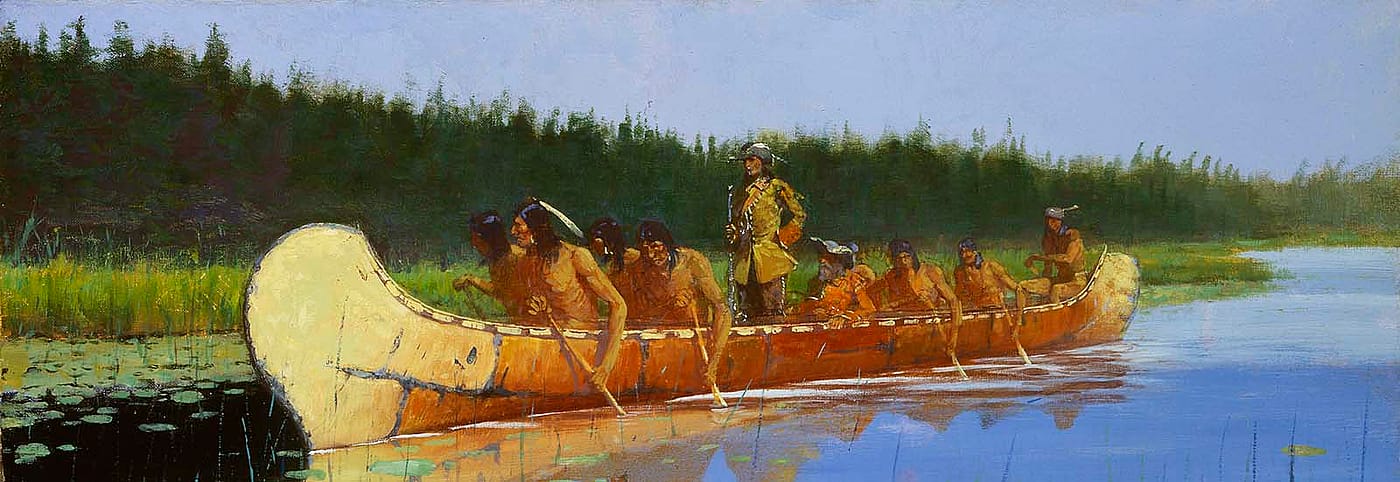

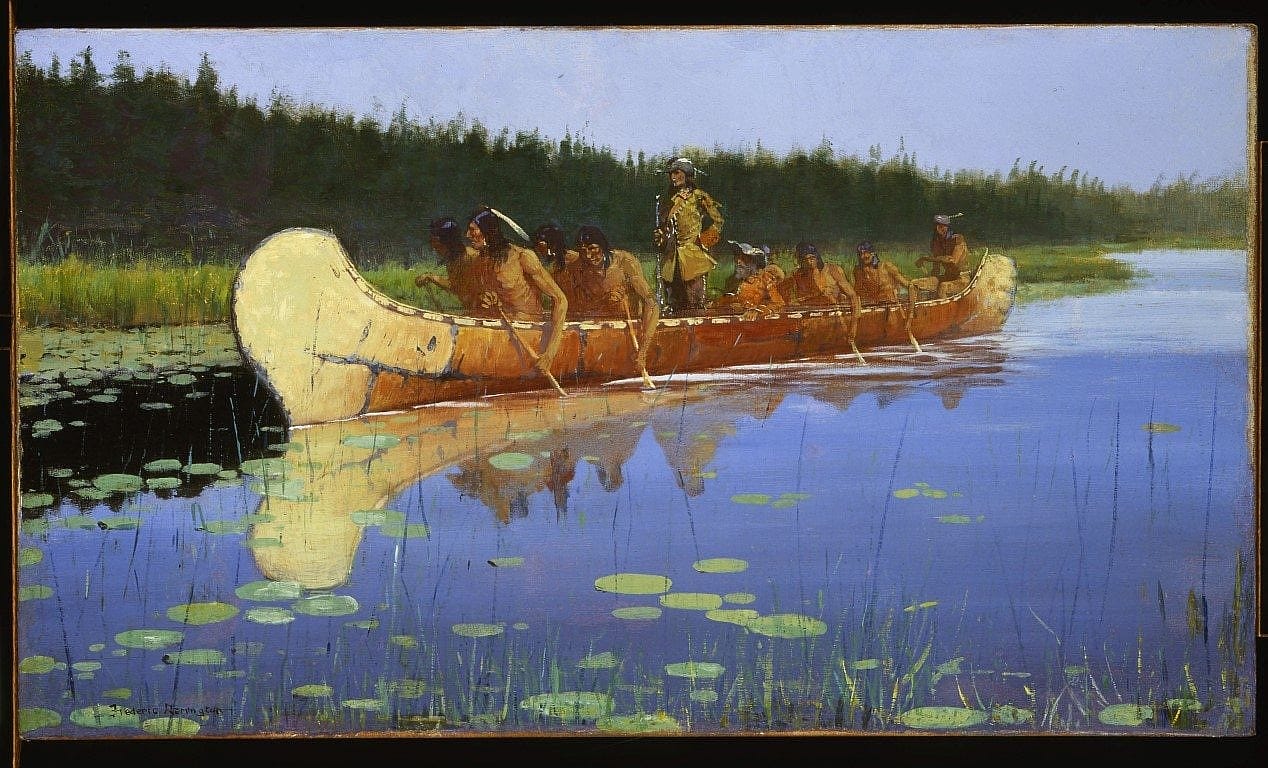

His notations are inconsistent and sometimes cryptic. Valuable data concerning an artwork’s history can be gleaned from his records, however, where his notations can be deciphered. For instance, next to the entry for de la Vérendrye, a painting from the Great American Explorers series of 1905, Remington wrote, “Sold McCoy Grand Rapids $300.'”5 Subsequently he noted “returned” and drew an arrow from “Raddison [sic]” also from the Great American Explorers series, two lines above, down to “de la Verendrye [sic].” In the same ledger book on page 69 next to “Pierre Raddison [sic]” Remington wrote “Sold McCoy. Grand Rapids.” Originally McCoy had bought the oil of de la Verendrye: he then exchanged it for the painting of Radisson and Groseilliers. A few years later Remington burned the remaining ten paintings from the series, eventually repainting one composition, The Unknown Explorers. Remington evidently forgot the de la Verendrye and Radisson switch because in his 1908 diary under “Paintings which I burned up.-” he lists, “The whole explorers series except for ‘La Verendrye [sic]:”6 Luckily his ledger book survives to clarify the events.

The ledger book that can be dated to roughly 1908 contains a list that Remington made of 162 paintings, specifying in some instances owners and prices.7 The artworks listed were executed between 1889 and 1908. Peggy and Harold Samuels, Remington’s biographers, refer to it as Remington’s “catalogue raisonné.”8 The list begins with the later version of The Last Lull in the Fight, copyrighted in 1903, and moves forward roughly chronologically until 1908. After the sixty-fourth painting, Remington back-tracked to 1889 and from there bounced back and forth in time until he finished his list, mostly with paintings that date to 1908. It is a spotty list of his work at best, and what his intentions were in compiling it and whether he did so from memory or from records is not known.

Remington’s wife, Eva, helped him maintain copyright records and did some of the bookkeeping related to the sales of his bronzes. After her husband’s death, Eva Remington appears to have kept track of the nineteen paintings on consignment at M. Knoedler & Co., and to have taken charge of the estate. She bequeathed Remington’s art and studio collection to the Frederic Remington Collection of the Ogdensburg Library Association, which published a catalogue of the studio artifacts in 1916, two years before Eva’s death.9 In addition, Eva left instructions to the Roman Bronze Works to make one cast of each of her husband’s bronzes not already in the Frederic Remington Collection and then destroy the molds.10 Like Remington, however, she never formulated a complete, methodical listing of her husband’s artworks and to whom they were sold.

Nor were the earliest scholars of Remington’s art concerned with identifying and locating all of his oeuvre; early interest focused on Remington’s illustrations. Merle Johnson, an artist and friend of Remington’s, began collecting Remington material as early as 1915. In 1929 he sold his collection consisting of two thousand Remington illustrations to The New York Public Library. Johnson had culled the illustrations from magazines and books and mounted them on cards preparatory to binding. He gathered together as well the articles containing Remington’s works and first editions of books with his illustrations, many of them with autographed letters from Remington or from the book’s author. In addition Johnson had collected prints and reproductions of many Remington paintings and sculptures. R. W. G. Vail, general assistant in the Reference Department of The New York Library at the time of the acquisition, wrote a scholarly essay on the artist. He based it on interviews of Remington by others, articles written about Remington either during his lifetime or by those who knew him personally, and on books authored by art critics contemporary to Remington.11

Johnson went on to form a second collection of Remington material, including mounted illustrations and books illustrated by Remington. In 1932 he sold that collection to the Denver Public Library, claiming that it was even more complete than the one sold to the New York Public Library three years before.12

In 1938, Theodore Bolton published a bibliography of books illustrated by Remington in American Book Illustrators.13 Although not complete, it was perhaps the first published listing, and was used by subsequent scholars. In the 1940s, Remington enthusiast Joseph McCarrell, a collector in San Francisco, gathered together Remington material that included original drawings, portfolios of prints, letters, first edition books illustrated by Remington and books mentioning Remington. The collection of 416 items was sold in 1950 through Argonaut Book Shop in San Francisco to western art collector Amon G. Carter, who in turn gave it to the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, Texas.14

Helen L. Card, a researcher and artist, began her research on Remington in the 1940s. She had a particular interest in American illustrators and began compiling tear sheet collections of their illustrations. Of Remington she said:

I discovered Frederic Remington’s pictures in

magazines and couldn’t find out anything about

him. I thought it was a shame that he wasn’t

recorded. So I began haunting the used bookshops

during my lunch hour and in my spare time, to find

out about him.

In those days-around 1940-you could buy

bound volumes and magazines quite cheaply…

So not just Remington, but the whole field of

American illustrators after 1870 opened up

before me.15

By the time World War II began, Card had compiled a large number of Remington illustrations into albums. E. W. Latendorf, owner of Mannados Book Shop in New York City, sold her first collection to The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Card compiled several other sets of albums of Remington illustrations, two of which are currently owned by J. N. Bartfield Galleries, New York, and a third owned by the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, a gift of Peter H. Davidson. She compiled scrapbooks of illustrations of other artists as well, completing nine more collections for The Metropolitan Museum of Art, including one on A.B. Frost.

During the late 1940s and into the 1950s, other historians studied Remington’s career, most notably Harold McCracken and Robert Taft. McCracken, historian and the first director of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, wrote several books on Remington including the still useful bibliography of Remington’s illustrations published in 1947, Frederic Remington: Artist of the Old West.16 Robert Taft, a scientist from Topeka, Kansas, researched and wrote on American photography and American illustrators, and was writing a biography on Remington at the time of his death.17 His unpublished manuscript provided valuable information concerning Remington’s youth, particularly regarding the years 1883 through 1885 in Kansas and Missouri, years which immediately preceded his decision to become an artist. Atwood Manley, a native of Canton, New York (Remington’s birthplace), and a former publisher of the St. Lawrence Plaindealer (previously owned by Remington’s father), wrote two essays in the 1960s on Remington’s childhood and “North Country” world, providing important information on this aspect of Remington’s background.18

Peggy and Harold Samuels published their biography of Remington in 1982. In the 1970s they began compiling a catalogue raisonné of all Remington’s oils, watercolors and drawings to publish in conjunction with the biography. Mailing out hundreds of letters to public institutions and private collectors, they began the arduous task of ferreting out and documenting artworks. Ultimately the Samuels decided to focus on the biography and put the catalogue raisonné aside. They generously donated their accumulated research to the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s Remington catalogue raisonné project. Additionally, in 1990 the Samuels published a list of Remington’s prints,19 an expanded version of Richard Myers’ 1970 bibliography of prints.20 Both are useful reference tools for researching prints of Remington’s art that were published during his lifetime.

Since Remington’s death in 1909, interest in his life and artistic career has persisted. The research of these early scholars has contributed immensely to the knowledge of Remington’s life and oeuvre and has facilitated the compilation of this catalogue raisonné of oils, watercolors and drawings.

Remington’s Art and Printing Processes

Although Remington usually exhibited his artworks at least once a year from 1887 to 1909 (with the exceptions of the years 1900 and 1902), most people were familiar with his art through reproductions in magazines and books and as prints, rather than through shows. When he had his first one-man exhibition and sale at the American Art Galleries in 1893, the viewers sought to buy the works they had seen published, that is, his illustrations. As one art critic noted, “Mr. Remington’s preeminence as the artist of the far West was readily recognized in the prices paid for his illustrations, while some of his paintings failed to reach the expected figures.”21

Two years later, in 1895, he held another one-man show and auction at the American Art Galleries, displaying 114 artworks. Again, his illustrations drew eager buyers. One reviewer noted, “Anxiety to secure black and white sketches by this popular man made bidding lively.”22 Another reviewer wrote, “Mr. Remington’s work in color is always a trifle hard and opaque. His gifts declare themselves in his black and whites.”23

Between 1882 and 1913 Remington’s drawings and paintings appeared as original illustrations in seventeen publications. Two of his earliest works, redrawn by staff artists, were published in Harper’s Weekly, one in 1882 and the next in 1885. Previous to this, in 1876 he had an illustration published in his college newspaper The Yale Courant,24 and in 1882 one in The Gridiron,25 the newspaper of St. Lawrence University. Eighteen eighty-six, however. marked the commencement of Remington’s career as an illustrator, a career that blossomed quickly and grew steadily thereafter. Harper’s Weekly published a total of fourteen of his illustrations that year and his work appeared in Harper’s Young People, St. Nicholas and Outing as well. In 1887 he added Harper’s Bazaar and the London Graphic to the list of publications seeking his work. He also received the prestigious commission to illustrate Theodore Roosevelt’s book, Ranch Life and the Hunting Trail which was published in 1888 by Century Company, and appeared serially in Century Magazine that same year.

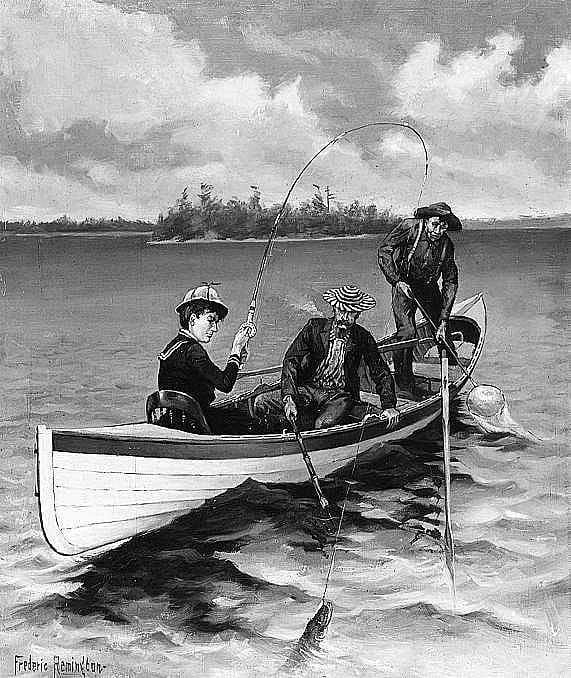

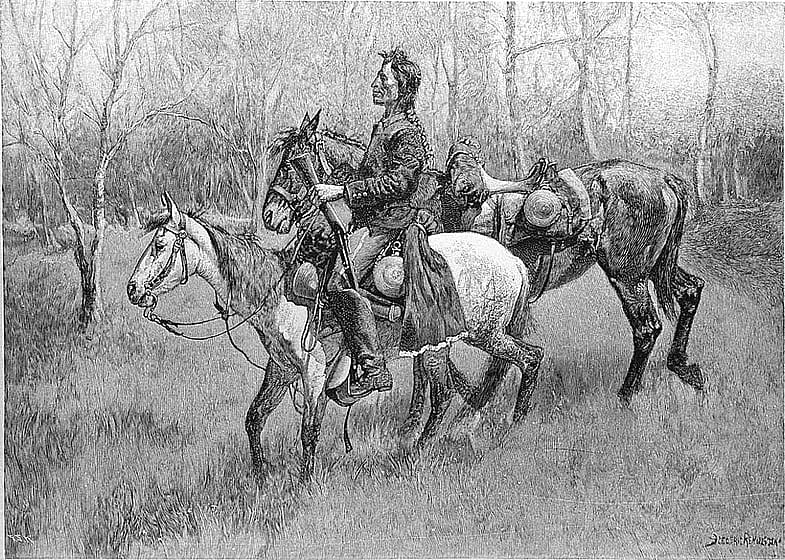

Remington’s vehicle, the magazine, imposed certain limitations on his art. The technology required to print an image along with text using a photomechanical screened halftone process was not developed until 1889, and not perfected until 1892. Many of Remington’s illustrations in the 1880s and the early 1890s, therefore, were published as wood engravings (Figure 1). Traditionally, in the wood engraving process, the artist’s original drawing was given to an engraver who sketched the image on a block of wood and, using a burin or graver, sculpted away the non-image parts of the design, leaving the design in relief and ready to be inked.26 Thus the engraver always came between the illustrator’s original depiction and what the public actually saw.

By the end of the 1870s, however, photography-on-the-block was developed. This process involved coating the block of wood with a light-sensitive emulsion and developing a photograph of the image directly on the wood. This enabled the graphic artist to be much more accurate in his translation of the original design to the wood block. In addition, by the early 1880s wood engraving had developed into a refined craft and highly skilled engravers were translating images onto wood for reproduction. Since large, double-page illustrations could take as long as three weeks to engrave, large blocks were cut up and distributed to several engravers to work on and then reassembled and bolted together for printing.27

Remington made concessions for the sake of the engraver. One was to work in black and white to help the engraver reproduce tonal values. He essentially translated color into gradations of black and white, which the engraver then reproduced with lines and dots. With the advent of process-line engraving (actinics), Remington made another concession, making pen and ink line drawings. As Joseph Pennell explains in Pen Drawinq and Pen Draughtsmen, the pen drawing “is photographed on to a sensitized block, gelatine film or zinc plate, or other substance, from which a mechanical or process engraving is made.”28 After the design was exposed on the plate the surface was treated chemically so that the design would absorb ink and the non-image areas would not. This process made possible exact copies of the original drawing and eliminated the need for handcrafted wood-cuts, the established means for reproducing line drawings. The illustrations that result from process-line engravings and wood-cuts are nearly indistinguishable; one would need to examine the printing plate as well.

With the rapid advances made in photomechanical technology, the nineteenth century saw a burgeoning of new methods used to reproduce original artworks. Graphic artists were at first hesitant to let go of traditional methods, and the public, fearful of inferior quality, was suspicious of the new processes. Engravers sought to make the illustrations and prints reproduced by the new techniques look like the results of the more traditional modes. Consequently process-line engravings mimicked the look of wood-cuts. Since process-line engravings were ubiquitous by 1886, it is highly likely that all Remington’s pen and ink drawings that appeared in the late 1880s and during the 1890s in books and magazines such as Outing, The Youth’s Companion and Century were reproduced as process-line engravings. Since we do not have the plates we have identified them as line engravings to acknowledge the possibility that some may be wood-cuts.29

To a much lesser extent, toward the end of the 1880s, Remington’s art was reproduced as photogravures, specifically for the oil paintings that appeared as illustrations in John Muir’s book Picturesque California30 and in Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha.31 An intaglio process, photogravure was a new printing technique in 1888. Unlike wood engraving and process-line engraving, it could reproduce tonal values by creating many small cells of varying depths intaglio surface, where the design was photochemically transferred. When inked, the deeper cells held more ink, the shallow cells less. When the image was printed, the deeper cells left thicker, darker ink deposits; shallower cells left thinner, lighter tones. The process was costly however, because the images had to be printed on an intaglio press, separate from text, and then bound together. It was used for small press runs of expensive books.

A process similar to photogravure was rotogravure, The two intaglio processes differed in that rotogravures were printed on roll-fed equipment rather than sheet-fed presses, and the design was etched on metal cylinders rather than the flat metal plates used in photogravure. Rotogravure was also fast and could accommodate large press runs. The artworks by Remington that were reproduced as rotogravures were issued as separate prints, such as those published by The Werner Company of Akron, Ohio, circa 1898. The Werner Company reproduced in a portfolio Remington’s fourteen illustrations for Nelson Miles’s autobiography, Personal Recollections.

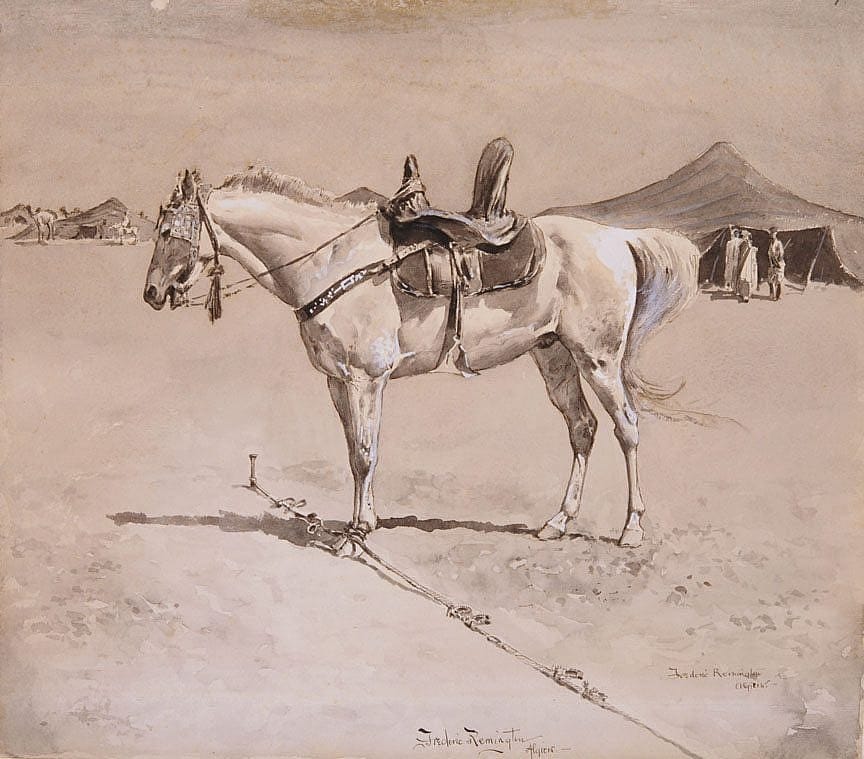

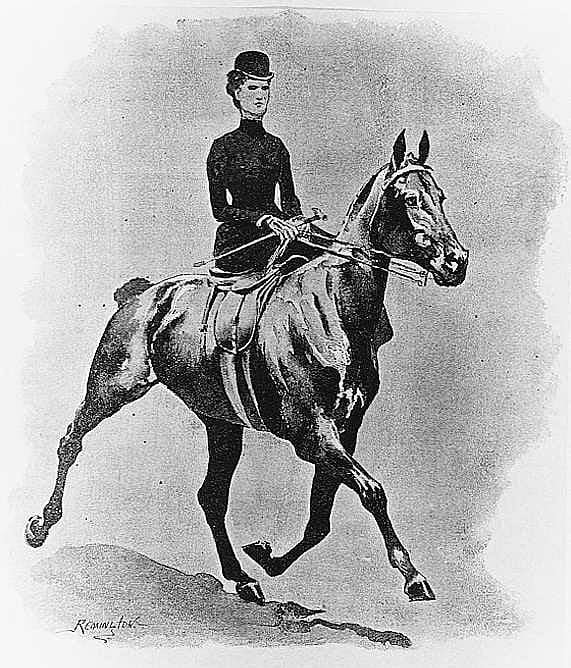

Patented as early as 1852, the process that produced the tonal values of images and allowed them to be printed along with text was finally perfected in the 1890s. The technology was the photomechanical halftone, and is exemplified in the illustrations such as Lady Rider, 1890 (Figure 2). The photo-engraving process entailed photographing the image through a fine screen, which created a pattern of dots, the number and size of which determined the lightness or darkness of any one area on the printing block. The dots were so small as to be invisible unless magnified. The result was an image that appeared to have a continuous range of tonal values, perfect for reproducing ink washes and oil paintings.32 Because early halftones lost definition when compared to the original artwork, graphic artists on occasion touched up by hand the photomechanically engraved plate to add texture to the halftone. As with process-line engravings, it is difficult to be specific about the exact reproductive methods involved without seeing the plate. For the purposes of the Remington catalogue raisonné, we have not speculated on whether halftones have been retouched by the engraver; instead we have labeled them simply halftones.

Magazines such as Harper’s and Century did not switch to using halftones immediately or exclusively, but used all three methods-wood engravings, process-line engravings and halftone-eventually phasing out wood engravings in the 1890s. Not long after the process of black and white halftones was refined, photomechanical color process halftones were introduced. Part of the process for color halftones also included photographing the artwork through a screen. Because the three or four colors were laid down atop each other using separate plates, not only is the screen pattern visible through a magnifying glass, but also the picture’s border reveals the edges of the color plates and the individual hues can be discerned. Examples of color halftones reproducing Remington’s art include the color illustrations in Collier’s Weekly between 1903 and 1913. Collier’s also issued many of Remington’s illustrations as individual prints and portfolios of prints. These, too, are color halftones. At times Collier’s referred to them as “Artist’s Proofs.” Traditionally, a proof is an impression of a print pulled before the plate, block or stone was finished, so that the artist could inspect it before it was published. By the nineteenth century, however, “proofs” were issued after the print was published to increase the size of an edition and had no relation to the original use of the word.33

To a lesser extent, publishers used black-and-white and color lithography, the latter also referred to as chromolithography,34 to reproduce Remington’s art. The best-known color lithographs were those in the portfolio A Bunch of Buckskins, published by R.H. Russell in 1901. The set of eight prints depicted mounted Western figures. In lithography the design to be printed was drawn on or transferred to a smooth stone or metal plate. The image held ink while the non-image areas were treated with a chemical solution so that they would not absorb the ink.

Another lithographic process used to reproduce Remington’s art in color was oleography. An oleograph is a chromolithograph that is printed on cloth or canvas and varnished to resemble an oil painting. The Last of His Race, the original of which is in the Yale Art Gallery, was reproduced as an oleograph. Because the print is on canvas and is varnished, it is a convincing reproduction and thus easily mistaken for an oil painting.

Because Remington’s art was reproduced in large numbers and distributed widely, it was often through reproductions that the public became familiar with his work. And since many of the paintings that he burned in 1907, 1908 and 1909 had already been illustrated and made into prints, it is due to graphic technology that these works are known today.

Remington’s Artistic Process

The research for the catalogue raisonné has clarified aspects of Remington’s picture-making process. From the beginning of his artistic career, Remington used several types of memory aids in the process of creating an artwork, including written notes, sketches, photographs, models and artifacts.

In his travel journal from his 1886 trip to New Mexico, Arizona and Mexico, Remington organized his observations into categories with captions such as “remarks,” “color notes,” “picture,” “frontier,” “Mexican” and “Army.” Some sections of the journal have been crossed out, as though Remington referred to them for an article or illustration, and then was finally finished with them, and so marked them off.

A typical entry under “color notes” reads, “In the broken country of western Arizona the earth is of a blue, red colormade cold in the shaddows [sic] and cold too in the sun though with marked difference. The mesquit [sic] of a certain kind is blue white green.”35 These reminders of the land’s hues helped Remington to recreate the scene when back in his studio.

In his journal, Remington’s approach to the Mexican natives, military and Indian tribes he encountered was at times anthropological. For instance, he documented how the Mexicans and Papagos harvested wheat and herded cattle and described their dress. For the Papagos, he noted their religious beliefs and festivals, their educational system and the fact that they had no written language. Remington made subjective comments and analogies to his own culture as well, such as comparing the size of pieces of dough to that of a baseball when observing a Mexican woman making tortillas.36 He jotted down narratives that he heard, such as one a First Sergeant told him while he was visiting the Tenth Cavalry in Tucson.37 The story, about Powhatan Clarke bravely rescuing Corporal Scott, became material for a future article and illustration.38

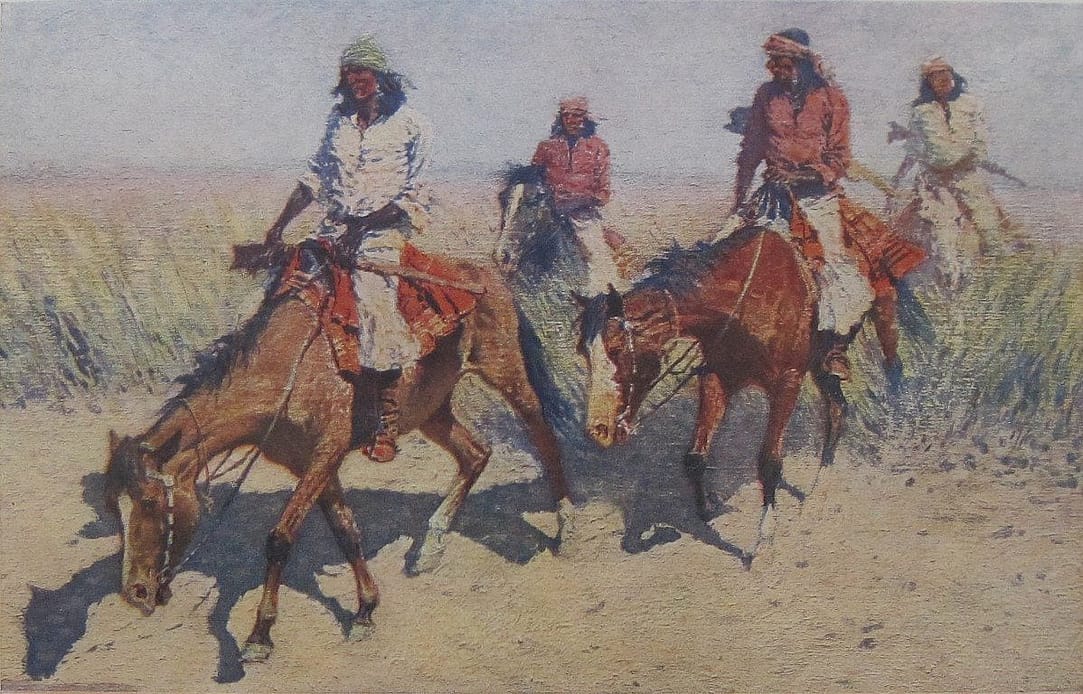

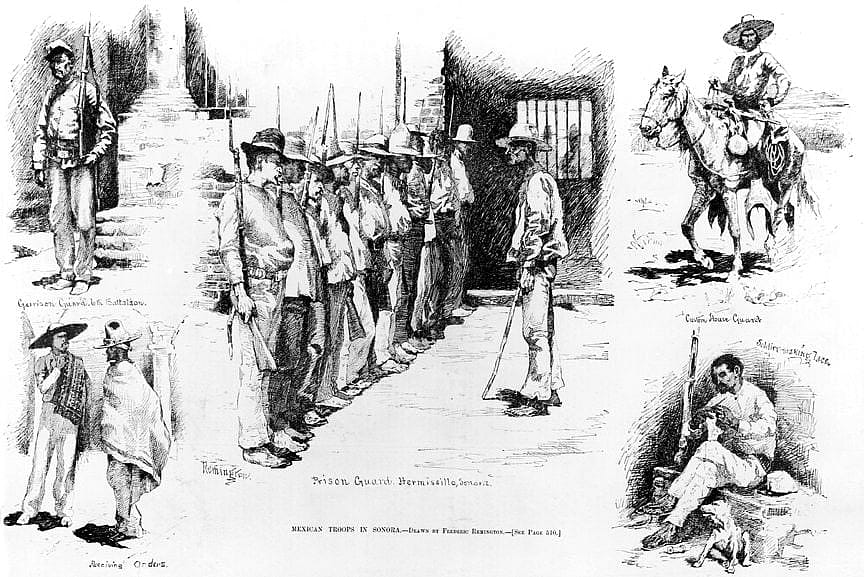

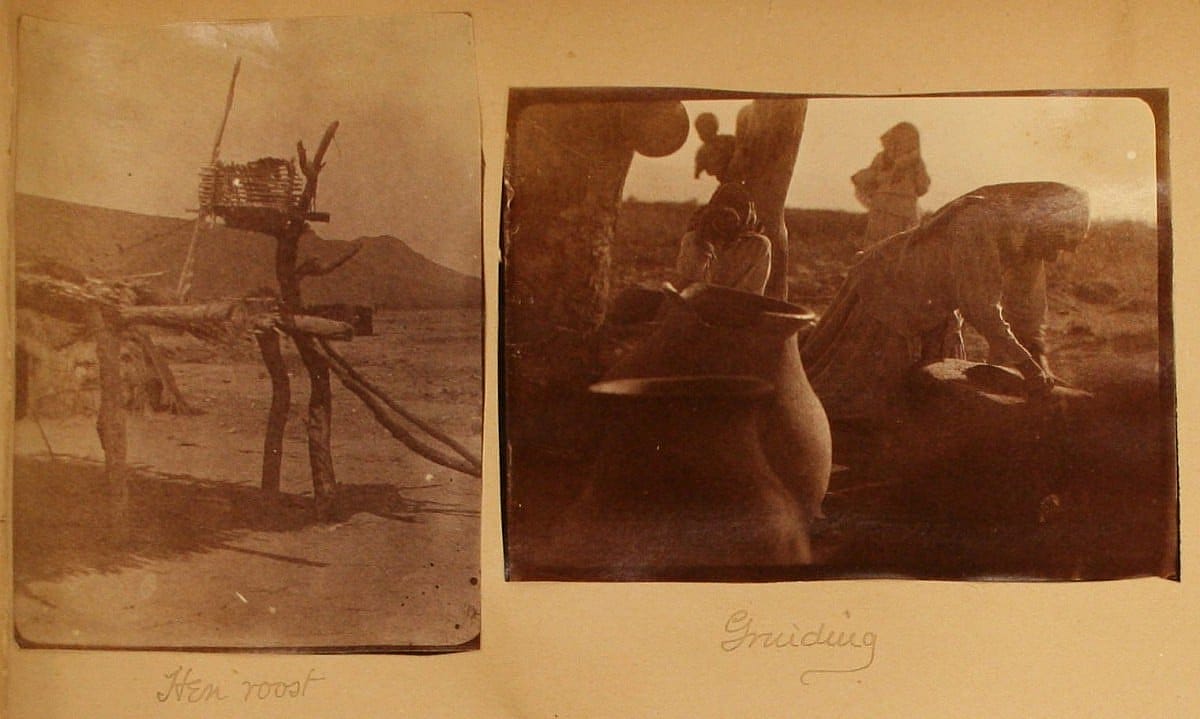

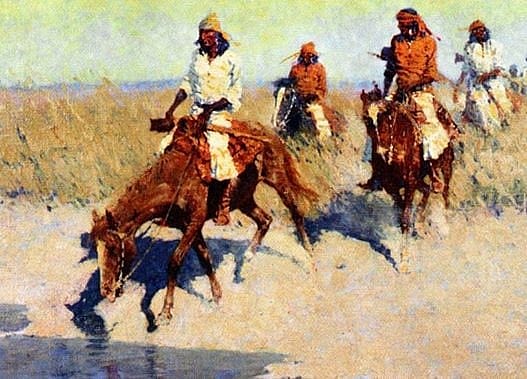

Remington supplemented his written accounts with photographs. He frequently noted in his journal that he was taking views and photographs. The Frederic Remington Art Museum owns six photograph albums as well as boxes of photographs. One of the albums39 is largely devoted to photographs taken on this 1886 trip and includes images of the Tenth Cavalry, Mexicans and their military, Apache and Papago Indians, towns and animals. Two illustrations composed of vignettes, Mexican Troops in Sonora and Sketches Among the Papagos of San Xavier (Figures 3 & 4) (published in Harper’s Weekly, August 7, 1886, and April 2, 1887, respectively), were based directly on photographs that Remington took. (Figure 5)

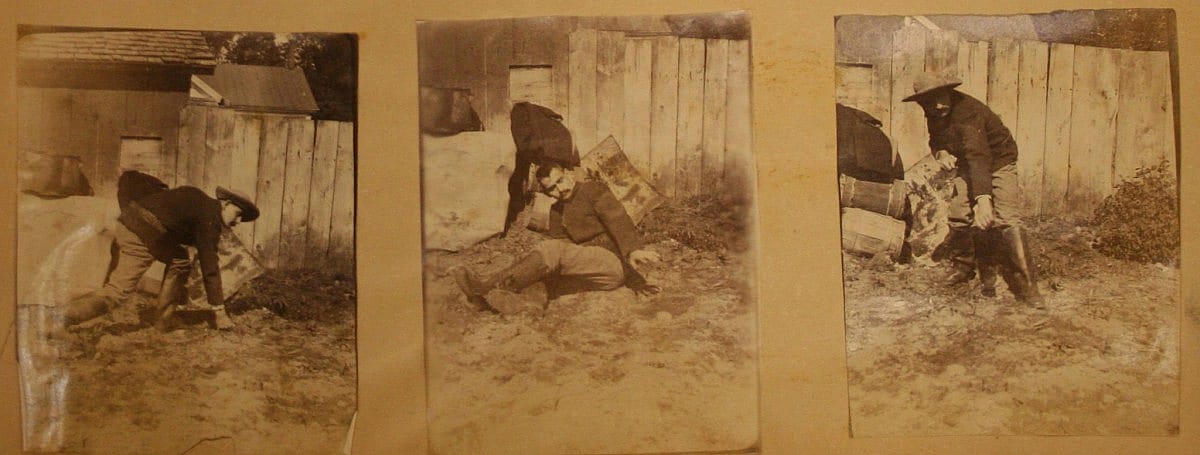

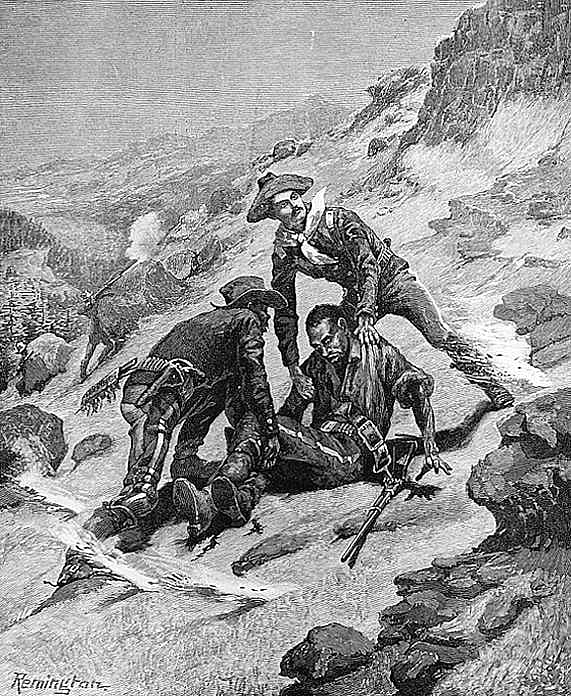

A sequence of photographs from this album demonstrates one way that Remington incorporated this visual information into a finished painting. While visiting General Miles at Fort Huachuca, he wrote in his journal, “Col. Royal this morning turned out a trooper for me[.] I photographed him in various attitudes and then made quick water color.”40 Among his photographs are three of the same trooper in different poses (Figure 6). Whether or not it is Private Kelly, the officer sent by Royal to model for Remington, is not certain. Nevertheless, Remington combined all three poses in a figural composition that depicts the narrative about Corporal Scott’s rescue recorded in his journal and mentioned above. The resulting illustration, Soldiering in the Southwest—The Rescue of Corporal Scott (Figure 7), was subsequently published in Harper’s Weekly along with the article on soldiers in the Southwest that mentions the heroics of Powhatan Clarke.41

Artifacts were also important reference tools. Remington collected material such as Indian, Mexican, Western and military clothing, weapons and tack plus Indian pottery and baskets to study and paint from when back in his studio. He was always on the lookout for material. His letters and journals record occasions when he purchased items himself or had others obtain and send them to him. For example, in his 1886 journal he records, “I bought 8 poisoned arrows of a old Indian and a bowl of good style of manufacture.” Two years later while traveling to Fort Grant, Fort Thomas and San Carlos Army Post in Arizona, Remington recounts, “I bought some Indian Wicker—etc.—”42

Remington wrote to Powhatan Clarke in November 1887, “I expect a lot of indian [sic] clothes from the agent of the Blackfeet soon … I got a coup stick this summer and they are harder to find than the devil.”43 He appealed to Clarke for photographs and also for items from the Southwest that he described specifically. He even told Clarke where to shop: “I wanted you to get me a buckskin Indian shirt without sleeves—big neck & short shirt—if you go to Tucson look up one at that dealer in Indian curios store.”44 He acknowledged receipt of the shirt in January 1888.45

Remington inventoried his studio in 1897, listing hundreds of items including “innumerable bead & quill Indian [sic] ornaments around mirror,” and “a long settle under which is too much stuff to enumerate—.”46 He continued to& collect. In 1900, in Ignacio, Colorado , he bought from H.L. (Ray) Hall, a licensed trader, In a letter to his wife from Ignacio dated October 29, 1900, Remington wrote, “I have 1 hide dresser—I lace— beaded belt 1 ute baby basket very fine—some Cliff dweller pottery and expect to get more.”47

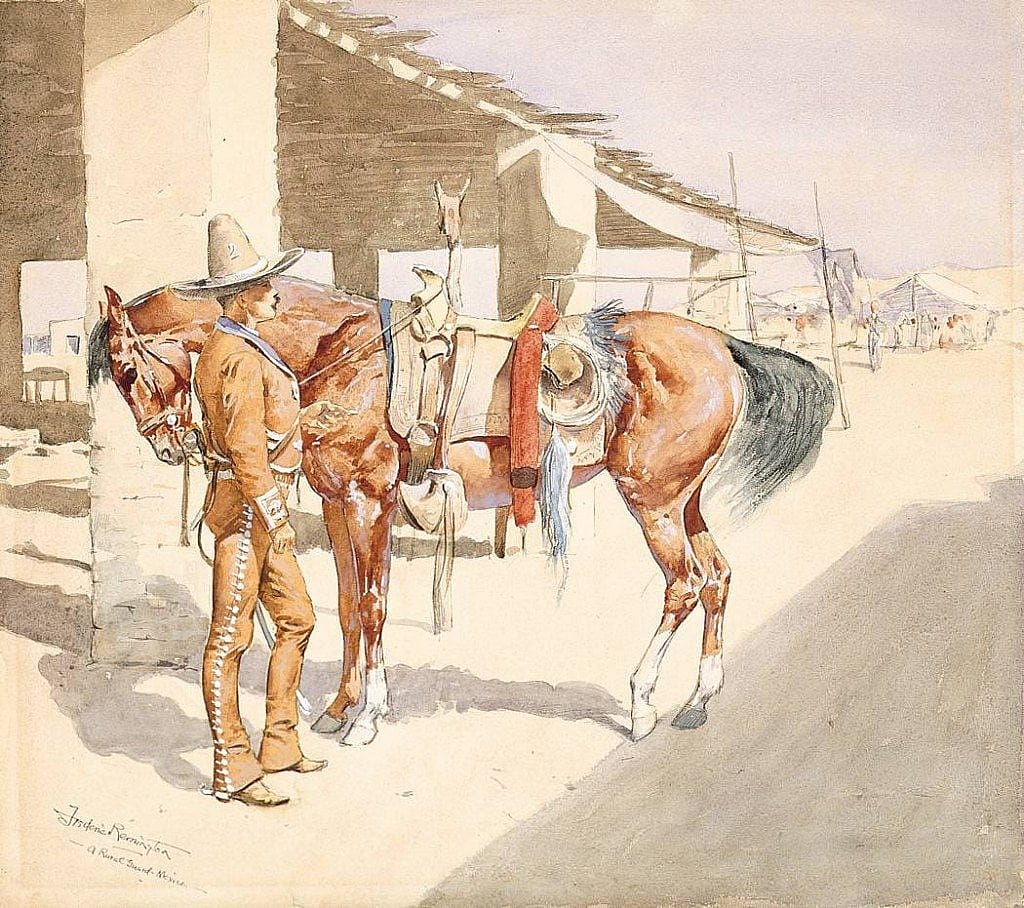

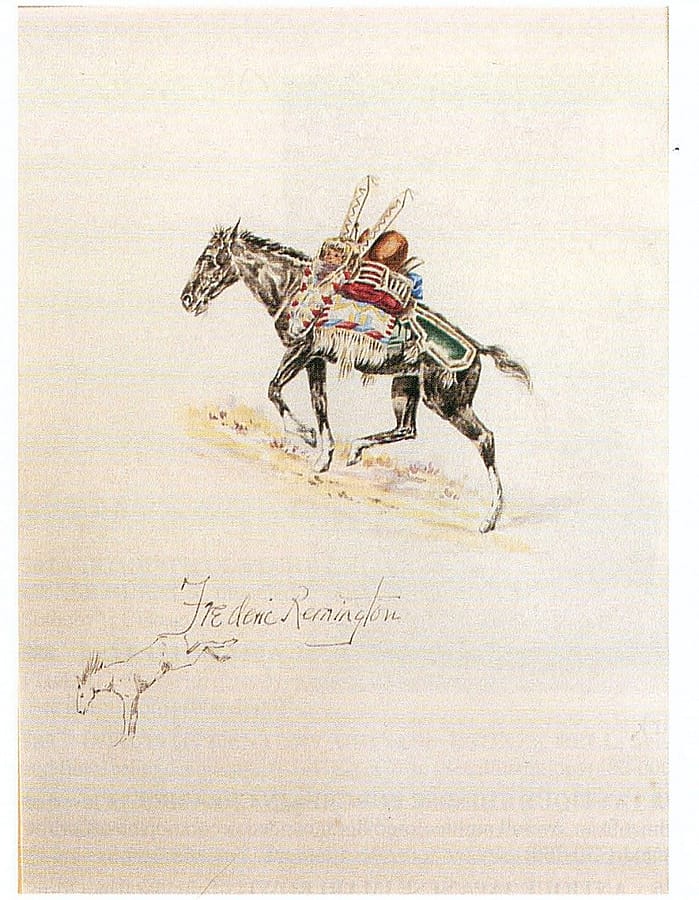

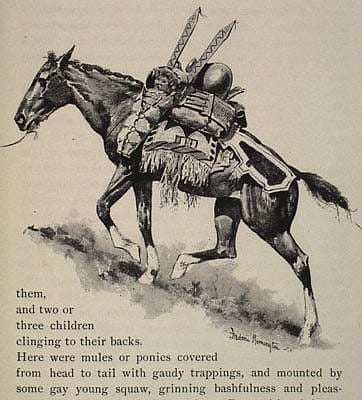

Remington used such studio artifacts as the wicker olla, Blackfeet leggings and shirt when making the pen-and-ink drawings and black-and-white oil paintings for The Song of Hiawatha. The Indian shirt depicted in Missing and The Buffalo Signal is from his studio collection, as are the Mexican hat and jacket in A Rural Guard-Mexico (Figures 8a, 8b, and 8c).

Borrowing ideas from photographs, color notes, and artifacts, Remington created unique compositions such as Post Office in Cow Country. Remington traveled west, to Wyoming and Montana. in 1899. He took many photographs of people, towns, animals, the landscapes and points of interest, including one of an axle-grease box that had been converted into a post office box outside Red Lodge, Montana. The box inspired Remington to create an entire painting. Using the box as a starting point, he duplicated the photograph almost exactly, although he changed the writing on the box to read Post Office Box instead of Mica Axle Grease. He set it in a prairie with mountains in the distance and created a figural group next to it. He inscribed the painting “Big Horn Basin,” a geographical region approximately thirty miles south of Red Lodge in Wyoming. Cody, Remington’s Wyoming destination on this trip lies in the northwestern corner of the Basin. The background hills resemble the McCullough Peaks east of Cody. There is a photograph of these hills in Remington’s album, but the painted ones are too generalized to make a positive identification. In fact, most of Remington’s mountain backdrops, while derived from photographs, sketches and memory, are generalized Western settings of barren hills and rimrock outcroppings that could just as easily be the Southwest, the Bad Lands or the high prairies of the Rocky Mountains.

The panoply of extant sketches reveals Remington’s process of working out ideas. In them he would isolate a portion of a proposed artwork such as a head, hands, a horse’s legs or a figure’s pose, rough out a picture’s entire composition or map out the compositions of several ideas in thumbnail sketches that would appear as individual illustrations together in a particular article. Remington sketched while traveling through Nebraska and North Dakota in 1905 with his friend, Henry Smith. Among the sketches from this trip is one inscribed “Bad Lands at Sunrise.” It was the basis for the small oil painting, Stormy Morning in the Bad Lands, in the Remington Studio Collection at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West.

In addition (Q pencil sketches and sketches with color notations, Remington painted color oil studies of people, animals (usually horses) and landscapes, a practice that increased as his career progressed. There are many recorded instances of Remington making color studies.48 In a letter to Eva Remington written from the Ute reservation in Ignacio, Colorado, and dated November 4, 1900, he wrote that he had ten color studies. While visiting Buffalo Bill’s Southfork ranch just outside of Cody, Remington recorded in his diary

on September 18, 1908, “I made two good notes in color & failed on a wagon study.” Four days later on September 22, he wrote, “I made photographs & one study of stables against the sun.”

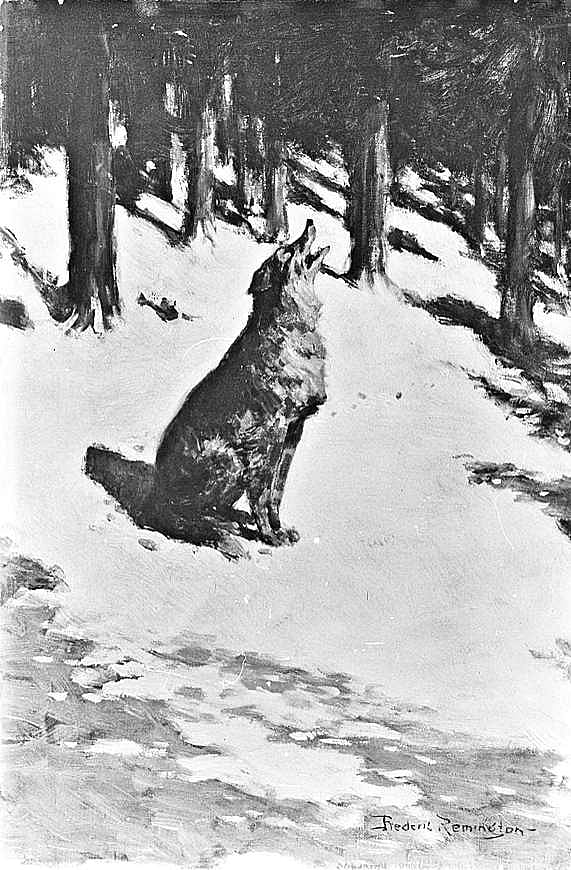

During the winters of 1908 and 1909, Remington made sketching forays into New England, producing over a dozen scenes of snowy, frozen landscapes. During his summers on Ingleneuk, once finished with his commissioned paintings for Collier’s, he would turn to painting landscapes. Some of these were color studies used as references for painting oils, but late in his career they were the final products.

Back in his studio Remington referred to these studies for color and compositional ideas. Sometimes he made a charcoal sketch on the canvas and painted the composition directly on the canvas. At other times he painted the landscape on the canvas and worked out the design of the figural part of the composition on paper. He then “laid” or transferred the figures to the landscape by tracing them onto a red conte-crayoned tissue laid on top of the canvas, leaving a red drawing of the figures behind which he would then paint.49 The red lines are still visible in Ghost Riders, apainting in theRemington Studio Collection at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West.

A late work by Remington that exemplifies his combined use of models, color studies and photographs is the equestrian portrait of Major General Leonard Wood. Wood posed for Remington in September 1909. Remington recorded the sittings in his diary:

September 5

two orderlies came with horses at 9.30. In great

wind I put easel out and Wood posed on a bay

horse. It blew terribly til I made a drawing.

Adjourned for lunch. Cleared fine from north &

at 2.30 we went at it again. I have a good start.

September 6

Fine clear day—We got in business and I finished

the mounted figure as best I could—a blazing light.

I also made a study from my studio window of the

chestnut& horse.

Remington also photographed Wood on his horse. Referring to the photographs and the oil studies, Remington worked on the painting during the following weeks. On September 16 he wrote in his diary, “I am drawing the Genl. Wood—” Four days later he recorded, “Fought and have the Wood picture on the go.” Finally on September 25 he wrote, “I worked hard and think the Genl. Wood portrait finished.”50

The seemingly finished and well-planned final product, however, was not always the last word for Remington. Research has revealed that Remington often came back to supposedly completed artworks, that at times had already been published and/or copyrighted, and reworked them. These changes can be tracked by comparing existing historical documents such as copyright photographs and illustrations.

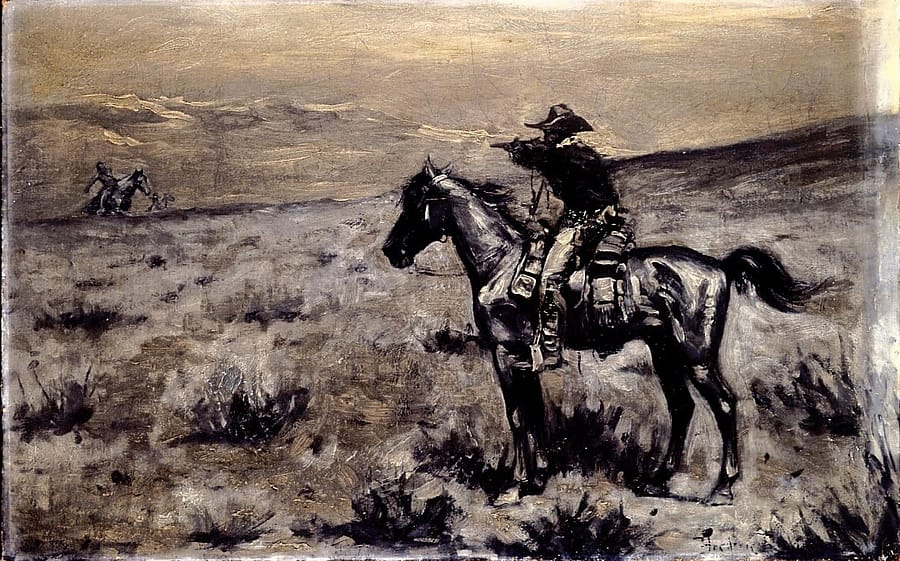

Numerous, subtle changes are found in Indian Scout with Lost Troop Horse (Figure 9). The illustration, reproduced as a wood engraving in Harper’s Monthly (June 1891), corresponds exactly to the copyright photograph of 1890 except for the omission by the engraver of the copyright information in the lower right, “Copyright 1890/by-” (Figure 10). The copyright photograph and the illustration, however, differ markedly from the original as it appears today. Compare, for instance, the signature and inscription, the rolled blanket behind the Indian scout, the scout’s hair ties, the decoration on the canteen, the rifle position and the attitude of the rider’s horse’s front right leg. In the transformed version, Remington eliminated the clutter of gear attached to the Indian’s saddle plus the rope around the horse’s neck, simplifying the scene. Why Remington made these changes is not known, but perhaps he intended to impart a greater sense of verisimilitude to the horse’s stride and present a more cohesive composition with no distracting and extraneous detail.

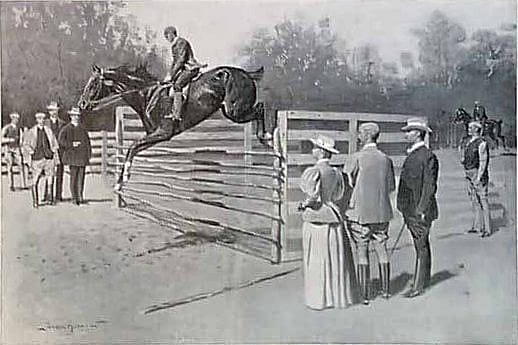

Other paintings exhibit more dramatic transformations. In Red Medicine, copyrighted in 1899, and illustrated in part in Done in the Open in 1902, Remington painted out the figures and bottle in the original oil painting, leaving only the boulder, settlement and distant mountains. Remington also painted out a figure in Getting Hunters in Horse-Show Form (Figure 11), originally published in Harper’s Weekly (November 16,1895) (Figure 12). In the article, “Remington-The Man,” published in Collier’s Weekly (March 18, 1905), Charles Belmont Davis, explained this transformation:

If we are to believe Remington, he once did

paint an individual with a skirt. She was part of

a picture which he had been commissioned to paint

of a well-known high jumper. The scene depicted

the horse flying over a high gate at an indoor

meeting, and, to add verisimilitude to the scene,

he painted in a girl as one of the interested audience.

The gentleman who gave the commission was

delighted with the photographic likeness of his horse

and accepted the picture at once, but on one

condition—that the lady be painted out of the picture

entirely.

In this case, then, it was not Remington’s choice but that of his patron. Also existent are artworks that have been cropped such as The Beef Issue at Anadarko, Harper’s Weekly (May 14, 1892) and On the Trail, The Cosmopolitan (October 1894). Although these compositions have been cut down, when compared to the illustrations it is apparent that the remaining portions have not been altered. It is possible that the missing sections had been damaged and so were cut off, either by Remington or subsequent owners.

Sometimes a painting never made it successfully off the easel. Remington revealed in his diary on July 20, 1909 that “Drought failed,” and wrote again on August 28, 1909, “I have thrown out Squaws with Buffalo Meat, it won’t do.” To completely repaint a subject was not unusual for him. There are documented occasions when, dissatisfied with a composition, he destroyed the canvas, sometimes years after originally creating it, and began anew.

The list of artworks from ledger book 71.837, circa 1908, in the Frederic Remington Art Museum archives has several entries indicating he destroyed paintings and painted them again. For example, next to “Tossing buffalo runner,” known officially as The Buffalo Runner, Remington added in parentheses, “Repainted. other burned.” The dimensions noted, 30 x 27 inches, are those of A Buffalo Episode, the later and extant version now owned by The Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma.51 Beside When His Heart is Bad and Unknown Explorers, Remington noted parenthetically “repainted other burned” and “Repainted old one burned up,” respectively.52

Remington did not record in his diary why he was dissatisfied with these compositions, but the transformed paintings reveal a cohesion and a simplification of detail missing in the earlier versions. This is most notable in When His Heart is Bad and Buffalo Runner, in which Remington replaced the horizontal formats for vertical ones, cropping out elements on the sides that distract from the primary event, and centralizing the main figures more forcibly. Remington enlarged the subjects and placed them more emphatically in the foreground, thus demanding the viewer’s attention.

As demonstrated. Remington’s approach to his craft was ongoing and evolving. In 1907 Remington made a bronze, The Buffalo Horse, of a buffalo tossing horse and rider. It is the same theme as and similar in composition to The Buffalo Runner and A Buffalo Episode. Perhaps working with the composition three-dimensionally in clay gave Remington new insight into the figural grouping’s possibilities.

Fakes and Tampered Variations

Writing a biographical sketch of Remington in 1929, R. W. G. Vail of The New York Public Library noted, “A curious commentary on Remington’s popularity is the fact that there are probably more forgeries of his works on the market to-day than of any other American painter.”53

That Remington’s work would be copied and faked during his own lifetime and after his death is not surprising. He was one of the best paid illustrators of his day. He signed a contract with Collier’s Weekly in 1903 stipulating that he would produce one painting a month to be reproduced in the magazine at $500 per painting, with a minimum order of twelve per year. The amount per picture was later raised to $ 1,000 with the minimum order remaining at twelve a year. Also his illustrations were popular and demanded comparatively lucrative prices during his lifetime. They still do today.

Among the inauthentic artworks attributed to Remington there are several categories, including pastiche, copy, fake, forgery and altered state. For the purposes of our catalogue we have used certain definitions for these terms. A pastiche is an artwork that borrows elements from two or more existing compositions to create a new artwork, and the intent to deceive is clear. A copy, on the other hand, is a literal transcription

of a single artwork. The size and medium may differ from the original, and sometimes it is a detail rather than the entire composition. The original purpose is not necessarily to delude; students routinely copy a master’s work as an artistic exercise. As the years go by, however, the initial purpose may be lost and the artwork mistaken for an authentic piece.

A fake is a new composition, one not derived from any known artwork, and signed with the artist’s name with the intent to deceive. The imitator chooses a subject associated with the artist he or she is attempting to imitate and uses the palette and brushwork associated with that artist as well. A forgery occurs when someone takes another artist’s work, paints out his or her signature and signs a forged signature of another artist. For our research, tampered variation applies to an artwork that has been altered by someone other than the original artist.

Copies of Remington’s art abound, perhaps because Remington was so widely published, giving the public ample opportunity to study his art. Those artworks published in Remington’s book, Drawings (1897), in Theodore Roosevelt’s book, Life and the Hunting Trail (1888) and the Collier’s Weekly illustrations published in color (1903-1913) seem to be particular favorites to copy. A copy of Pool in the Desert (Figure 13) was certainly based on the illustration in Collier’s Weekly (Figure 14) or the subsequent Collier’s print. Like those reproductions, it is a cropped version of the original painting (Figure 15), and does not reflect the changes Remington made to the oil after it was published.

Lone Rider is an example of a Remington fake (Figure 16). The composition, not based on any known Remington artwork, depicts a cowboy riding in a prairie with mountains in the background and a buffalo skull in the lower right corner. Although the style is not Remington’s, the scene is in black and white, which was typical of Remington’s work for illustration before 1903. Certainly the subject matter suggests a Remington artwork.

An interesting example of Forgery is in Disengaging the Chetah [sic] from Its Prey. The painting is actually by Gilbert Gaul, an artist contemporary to Remington. It was published in Century Magazine (February 1894) to illustrate the article, “Hunting with the Chetah [sic]”. At some point, however, someone painted out Gaul’s signature in the lower left and in the lower right signed “Frederic Remington,” and the work was sold at auction in 1945 as a Remington original.

Typical examples of the tampered variation category, to which someone other than Remington has made changes or additions, are the many original Remington sketches that bear a Remington signature by another hand, which, rather than enhancing them, may even decrease their market value. The most frequently seen forged signature is that referred to as the “kicking horse signature.” It is thought to have been developed by someone in the Midwest early in the twentieth century. This imitator, it is believed, worked with a dealer out of Chicago who purveyed original Remington artworks as well as fake ones throughout the Midwest, in Detroit, St. Louis, Minneapolis and Milwaukee. His “kicking horse signature” is commonly found in books, either alone (Figure 17) or with the inscription, “My Book”. In one example, the author of the kicking horse signature hand-watercolored the illustrations by Remington in Francis Parkman’s 1892 book, The Oregon Trail, passing it off as the work of Remington.54 Sometimes the kicking horse signature also accompanies a watercolor derived directly or loosely from a Remington composition (Figure 18). Watercolors consistent in style to those with the kicking horse signature have also been Found on title pages or scattered throughout books and signed simply “F. Remington.”

The work of this person has appeared decorating the books of Eugene Field Sr., a respected nineteenth-century journalist and children’s poet who lived in Sr. Louis and died in 1895. Remington made a pen-and-ink drawing that was illustrated in one of Field’s books, Field Flowers, published in 1896.55 Interestingly, there is a watercolor copy of this drawing. stylistically matching the work of the kicking-horse-signature artist, on the title page of a copy of another of Field’s books, Songs from Childhood. As in the other instances, it is falsely ascribed to Remington.56

Another example of tampered variation is when a print is touched up to make it appear like an original. Among Remington’s artworks, this happens most Frequently with The Last of His Race, a painting that dates to 1908 and depicts an Indian standing at the edge of a bluff overlooking an expanse of land. In the same year that it was painted, Brown and Robertson Co. in Chicago reproduced it as an oleograph. Because an oleograph is printed on canvas and then varnished, the print has confused collectors who have mistaken it for a real painting. The fact that in this case the print is approximately the same size as the original oil painting has added to the confusion. An example of this print (now in the Buffalo Bill Center of the West) has been tampered with to make it appear even more original. Someone altered it by touching up areas of it with paint, perhaps in an attempt to conceal the fact that it is a print.

In addition to inauthentic artworks, artists have plagiarized Remington’s art both during his lifetime and since, by stealing compositional ideas from his works, incorporating them into their own and not crediting the source. George Berger, a Denver artist active during the 1890s, borrowed Remington motifs and claimed them as his own. Berger illustrated a picture book of scenic views of Colorado titled Gems of Colorado Scenery, initially published in the early 1890s.57 The book was a collection of photographs by William Henry Jackson. Berger made vignette drawings that appeared in the margins, several of which he copied directly from Remington pictures. Two of the compositions that he borrowed from Remington without crediting him were Bucking Bronco and Register Rock, Idaho. He incorporated the Remington motifs into new settings, but there is no question that they were derived from Remington’s art.58

The various fakes and copies eventually make their way into the art market as original artworks by Remington. The research for the Remington catalogue raisonné has identified some of Remington’s choice of materials. He often purchased his supplies from the artists’ suppliers H. Scott and F. W. Devoe. A standard size for a canvas was 27 x 40 inches, and in 1908 and 1909 he began using what he referred to as “rough” textured canvas. A “Whatman” water mark is frequently found on the watercolor paper he used, and his framers were Ahsler & Stabb and Thos. A. Wilmurt & Son. Knowledge of Remington’s materials is helpful, but not conclusive because many Remington canvases and academy boards have no artists’ supplier stamp; his canvases do not always measure 27 x 40 inches; and his watercolor papers do not always have watermarks. Ultimately it is connoisseurship—intimate knowledge of Remington’s style and technique in the various stages of his career, his brushwork and handling of paint, his hatching methods with pen and ink and familiarity with his artistic process—that determines whether or not an artwork is original.59

Lost and Found

Over the course of researching the Remington catalogue raisonné, more than 3,000 oils, watercolors and drawings have been catalogued. Not all of these artworks have been located, however, and for some, no information other than title has been found. New information continues to surface, revealing new titles and locations, while located artworks contiue to change hands and the information of their whereabouts becomes outdated. Although research has answered questions, it has also raised new ones. Approximately 2,700 of the catalogued artworks have illustration records, so that although in some cases the current location is unknown, at least a pictorial record exists.

The research has also brought to light artworks for which there is no pictorial record. They are known by title, although in some cases a verbal description exists. The titles of these unpictured artworks have been found in archival material pertaining to Remington, such as his ledger books, diaries, letters and the exhibition records dating to Remington’s lifetime. These artworks raise certain questions: Are they lost artworks that exist but have yet to be discovered? Are they lost forever either because Remington destroyed them without recording his action or because they were destroyed by someone else? Remington lists artworks “burned” or “ruined” for which there are no images, such as, The Two Vatatcos and With the Creeping Shaddows [sic] Come Bad Spirits.60 These paintings, then, are certainly lost unless new material surfaces.

Other artworks known by title only, such as Buying Mexican Cattle and The Manigua Gang, raise another question. Are some artworks known today by another title and therefore not lost at all? This was the case for Stormy Morning in the Bad Lands in the Remington Studio Collection at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. It is a signed small landscape inscribed, “Indian camp on Cheyanne [sic] River,” but no official title had been determined. Research revealed that it was indeed a finished oil which had been exhibited at Noé Galleries in 1906. This was discovered when a copyright photograph of it was found in the Frederic Remington Art Museum’s archives with the title, Stormy Morning in the Bad Lands, on the back of the photograph. Soon after, a copyright record at the Library of Congress, submitted by Remington on January 18, 1906, was located that gave a written description of Stormy Morning in the Bad Lands that matched the studio painting: “Oil painting 12 by 18 inches. Two Indian teepes [sic] in middle ground, with a line of bad lands, as such formation in Dakotas are called, the background.”

More data surfaced that helped to establish the history of this painting. Remington listed it in his ledger book (FRAM 1918.266) with paintings exhibited at Noé Galleries in 1906. A checklist from this exhibition included the painting, and a review in the New York Times (February 10, 1906) mentioned it, albeit negatively: “On the other hand, he fails to suggest atmosphere and movement in Stormy Morning in the Bad Lands.”

Several other oil paintings in the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s Remington Studio Collection are signed, finished oils that were probably titled by Remington and possibly exhibited. A few of the scenes depicted could easily match titles such as The White Birches, The St. Lawrence River, A Ranche [sic] and The Birch Forests, which were small landscapes that Remington exhibited at Knoedler’s in 1908 and 1909. Until more information surfaces, however, a conclusion cannot be reached as to whether or not these works were the exhibited paintings.

Evidence of another lost painting was found on the back of a pen-and-ink drawing titled Questionable Companionship. An inscription in Remington’s hand on the back of the support reads, “‘Questionable Companionship’—drawn from the painting by Frederic Remington.—” The catalogue for an 1890 exhibition at the American Art Galleries lists an oil of this title by Remington and a sketch of the composition by Remington has been located. No clues, however, hint at what may have become of the original oil.

Paintings that are certainly lost are those listed in Remington’s ledger books and diaries as having been destroyed. In at least three instances in 1908 and 1909, Remington recorded in his diaries that he threw out drawings and burned canvases. He considered them “early enemies” and “failures.” Unfortunately Remington did not always list each artwork by title. In 1908 he wrote in his diary, “burned up drawings,” a reference much too vague to make any identifications. It was learned from a collector that her father, with Remington’s permission, rescued three pen-and-ink drawings from Remington’s trash. How many other drawings were less fortunate?

Voice of the Hills, 1905. Oil on canvas. Private collection. Last known at Parke-Bernet, New York, 1955. Photograph Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (CR# 02765)

For a large group of artworks, images either from illustration or copyright records exist, but the artworks themselves have not been found. For some of these works the earlier provenance is known, but the list of past owners is incomplete and as yet the artworks’ present locations are unknown. For instance, two enigmatic paintings, Voice of the Hills (Figure 19) and Hole in the Day, were both copyrighted in 1906 and sold through the auction house Parke-Bernet Galleries Inc., the former in 1955 and the latter in 1964. Their current locations, however, have yet to be determined.

There are cases, however, in which the locations of these illustrated or copyrighted works have been discovered. Sometimes months or years can be spent trying to track down an artwork to no avail, and at other times an artwork suddenly turns up. One example of this is Russian Infantry Going to the Front (Figure 20). It was fortuitous to find a 1904 copyright record and photograph of it at the Library of Congress, and this had been the only mention of the painting found thus far. Although it was similar in composition and subject matter to paintings made by Remington for illustration in Collier’s Weekly (1904-1905) depicting the Japanese-Russo War, Collier’s evidently did not select it for publication. It was a welcome surprise, therefore, to receive a call from the owner who wanted more information on it because it was in her family’s collection.

Another example of an art work turning up is The Flag of Truce in the Indian War (Figure 21). This was the first art work that Remington exhibited with the American Water Color Society. A pen and ink of the composition was illustrated in the catalogue for the show. From Remington’s records we knew it had sold to Samuel B. Duryea, of 8rooklyn, New York. It was serendipity that the goauche remained in the family and that more than a century later a decendent of his should call us. There have been several finds of paintings for which there is no archival record, such as The Cowboy (Desert Caballeros), The Cowboy (private collection) and The Alert (private collection). Connoisseurship has determined their authenticity. They bring up the question, however, as to how many other art works, never published during Remington’s lifetime and still undocumented, have yet to come to light.

It is the nature of this type of extensive research to persistently raise questions as it answers others. The research has shed light on Remington’s own means for organizing his oeuvre, further illuminated his working methods, added to our knowledge of the development of his style, clarified the multiplicity of printing processes that were used to reproduce his art and tantalized us with hints of artworks that he created but are to be found or are lost to us forever. Even after publication of the catalogue, our research, built upon that of many scholars, will continue to evolve and expand as new information comes to light.

ENDNOTES

1. William Dwight Whitney, supervisor, The Century Dictionary: The Encyclopedia Lexicon of the English Language (New York: The Century Co., 1895), vol. I, p. 855; Harrap’s New College French and English Dictionary (Lincolnwood, Illinois: National Textbook Company, 1987), p. 614.↩

2. For further discussion of art historical research see: Elizabeth Blakewell, William O. Beeman, Carol McMichael Reese and Marilyn Schmidt, general editor, Object, Image, Inquiry. The Art Historian at Work (Santa Monica, California: J. Paul Getty Trust, 1988).↩

3. See, Adalyn Breeskin, Marry Cassatt: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Graphic Work, rev. ed. (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian, 1980) (a new edition has been completed by Adelson Galleries, New York); Carol Clark, Milton Brown, Nancy Matthews, Gwendolyn Owens, Maurice and Charles Prendergast: A Catalogue Raisonné (Munich: Prestel-Verlag, 1990); Carol Clark, Thomas Moran: Watercolors of the American West (Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 1980) (a catalogue of Moran’s oils is currently under the supervision of Stephen Good); Ron Tyler, ed. Alfred Jacob Miller: Artist on the Oregon Trail (Fort Worth, Texas: Amon Carter Museum, 1982), with a catalogue raisonné by Karen Dewees Reynolds and William R. Johnston. Lloyd, Edith Goodrich, and Abigail Gerdts, Record of Works by Winslow Homer, vols. I-III, (New York: Spanierman Gallery, 2005). Ronald Pisano, William Merritt Chase: The Complete Catalogue of Known and Documented Work (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2007). Stuart Feld, President of Hirschl and Adler Galleries, New York, and Kathleen Burnside are compiling a catalogue raisonné for Childe Hassam. For additional information about these projects and others see Marie Louise Kane, “The Last Word,” Antiques and the Arts Weekly, Newtown, Connecticut, August 28, 1992, p. 1, 64-66.↩

4. Frederic Remington, ledger book 1918, 266, Frederic Remington Art Museum Archives, Ogdensburg, New York (hereafter referred to as FRAM), p.72.↩

5. Ibid., p.15.↩

6. Frederic Remington, 1908 diary, FRAM.↩

7. Frederic Remington, ledger book 71.837, FRAM, p. 4-8.↩

8. Harold and Peggy Samuels, Frederic Remington: A Biography, No. 841 (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1982), p. 509.↩

9. Ogdensburg Public Library, Catalogue of the Remington Collection (Ogdensburg, New York: Ogdensburg Public Library, 1916).↩

10. Eva Remington, Last Will and Testament of Eva A. Remington, ca. 1918, FRAM.↩

11. R. W. G. Vail. “The Frederic Remington Collection.” Bulletin of The New Public Library, Vol. 3, No.2 (February 1929), p. 70-75.↩

12. Malcolm Glenn Wyer, Western History Department: Its Beginning and Growth (Denver: Denver Public Library, 1965), p. 9.↩

13. Theodore Bolton, American Book Illustrators (New York: R. R. Bowker, 1938).↩

14. Argonaut Book Shop. An Extremely Important Collection of the Work of Frederic Remington Consisting of Original Drawings, Autograph Letters, Books Written &. Illustrated by Him, Portfolios, Prints, Posters and Periodicals, catalogue 14 (San Francisco: Argonaut Book Shop, c. 1950).↩

16. Harold McCracken. Frederic Remington: Artist of the Old West (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co., 1947).↩

17. Robert Taft, Photography and the American Scene (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1938, reprinted New York: Dover Publications. 1964; Robert Taft, Artists and Illustrators of the Old West (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1953); Robert Taft, Remington biography manuscript, Kansas State Historical Society, Topeka, Kansas.↩

18. Atwood Manley, Frederic Remington in the Land of His Youth (Canton, New York: Privately printed, 1961) and “Frederic Remington and the University,” St. Lawrence Bulletin, Vol. 24, NO.2 (Winter 1966). p. 4-7.↩

19. Harold and Peggy Samuels, Remington: The Complete Prints (New York: Crown publishers, Inc., 1990).↩

20. Richard G. Myers, A Guide to Old Remington Prints and Lithographs from 1888 to 1914 (Ogdensburg, New York: Ryan Press, Inc., 1975).↩

21. “Mr. Remington’s Pictures. Something Less Than 100 Works Fetch Something More Than $7,000,” New York Sun, January 14, 1893, p. 2.↩

22. “The Remington Pictures Sold. American Art Association Now to Dispose of Chinese Porcelains, Enamels, Jades, and Crystals at Auction,” New York Times, November 21, 1895.↩

23. “The Chronicle of Arts. Exhibitions and Other Topics. A Masterpiece by Turner and the Necessity for Putting It In Our Museum-One Of Sir Joshua’s Classical Attempts-Some New Drawings by Americans-Mr. Frost, Mr. Remington and Mr. Abbey-The Hollyer Platinotypes-Gaillard’s Engravings,” New York Daily Tribune, November 17. 1895.↩

24. Frederic Remington, “Good Gracious, Old Fellow. What Have You Been Doing With Yourself?” in The Yale Courant. “College Riff-Raff,” Part IV, November 2, 1878, p. 47.↩

25. Frederic Remington, A Class in Surveying. Illustrated in The Gridiron, Beta Zeta Chapter of Beta Theta Pi Fraternity, St. Lawrence University, Canton, New York, 1882, 2nd issue, p. 84.↩

26. Victor Strauss, The Printing Industry (Washington, D.C.: Printing Industries of America, Inc., 1967), p. 208-209.↩

27. Taft, Photography and the American Scene, p. 420, fn.↩

28. Joseph Pennell, Pen Drawing and Pen Draughtsmen (London: Macmillan and Col, 1889, 1894), p. 11.↩

29. For a thorough discussion of process-line engravings (actinics) and the panoply of nineteenth century printing techniques used to reproduce the art of Remington. Howard Pyle and others, see Estelle Jussim, Visual Communication and the Graphic Arts. Photographic Technologies in the Nineteenth Century (New York: R. R. Bowker Company, 1983.)↩

30. John Muir, ed., Picturesque California (San Francisco: J. Dewing Publishing Co., 1887, 1888).↩

31. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, The Song of Hiawatha (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1891).↩

32. Strauss, The Printing Industry, p. 180-181.↩

33. Bamber Gascoigne, How to Identify Prints (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1986) p. 206.↩

34. In How to Identify Prints, section 28b, Bamber Gascoigne explains, “In the heyday of reproductive colour lithography (the second half of the nineteenth century) the term chrornolithograph became firmly attached to all such prints …. The term is of no use for defining a specific category of print …. however, the term chrornolithograph remains useful to describe a historically significant and easily recognizable tradition of commercial colour lithography… “↩

35. Frederic Remington, Journal of a Trip Across the Continent Through Arizona and Sonora Old Mexico, 1886, manuscript, Kansas State Historical Society, Topeka, Kansas. n. p.↩

36. Ibid., n. p.↩

37. Ibid., n. p.↩

38. “Our Soldiers in the Southwest,” Harper’s Weekly (August 21, 1886), p. 535.↩

39. Photograph album 71.832, FRAM.↩

40. Remington, Journal, 1886. n. p.↩

41. Ibid.↩

42. Frederic Remington, House Book, 1888, journal of trip to southwest, Kansas State Historical Society, Topeka, Kansas, p. II.↩

43. Remington to Lt. Powhatan Clarke, November 3, 1887, Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis, Missouri.↩

44. Remington to Lt. Powhatan Clarke, [1887], Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis, Missouri.↩

45. Remington to Lt. Powhatan Clarke, January 3, 1888, Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis, Missouri.↩

46. Frederic Remington, “Inventory—Remington’s 301 Webster Ave. New Rochelle, N.Y. Studio,” June 18, 1897, manuscript, FRAM.↩

47. Remington to Eva Remington, October 29. 1900, FRAM.↩

48. Remington to Eva Remington, November 4, 1900, Owen D. Young Library. St. Lawrence University, Canton, New York.↩

49. Peter H. Hassrick, “Remington: The Painter,” Frederic Remington: The Masterworks (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1988), p. 139.↩

50. Frederic Remington, manuscript, 1909 Diary, FRAM.↩

51. Remington, ledger book 71.837, FRAM, p. 5.↩

52. Ibid., p. 8.↩

53. Vail, “Remington Collection,” p. 73.↩

54. Conversation with Rudolph Wunderlich. owner of Mongerson-Wunderlich Galleries, Chicago, Illinois, May 1994.↩

55. Eugene Field, Field Flowers (Chicago: A.L. Swift & Co., 1896), illustrated n. p.↩

56. Eugene Field, Love Songs From Childhood (Chicago: Eugene Field, 1905, copyrighted by Eugene field, 1894, illustrated in sheet).↩

57. Gems of Colorado Scenery (Denver: Frank S. Thayer, c. 1892), unpaginated. There are as many as thirteen editions of the book and the vignettes vary from edition to edition.↩

58. For discussion of twentieth-century artists who have borrowed Remington motifs and have incorporated them into their work, contact the Montana Historical Society, Helena, Montana, for a recording of Brian Dippie, “The Enduring Magnetism of the Little Big Horn: Artists and the Mythic Moment,” delivered at the Little Big Horn Legacy Symposium, Montana Historical Society, Helena, Montana, 1994.↩

59. Acknowledgements go to Rudolph Wunderlich and James H. Maroney for their thoughts concerning the terminology for inauthentic artworks.↩

60. Remington, ledger book 1918.266, FRAM, p. 59, No. 6 and p. 72, No. 18, respectively.↩

Written By

Emily Wilson

Emily Wilson is the curatorial assistant at the Whitney Western Art Museum. She is a big fan of contemporary art and taxidermy. Living in the West has made her appreciate the region for its artistic and aesthetic draw.