A Breechloader, the Civil War, and A Lawsuit: The Morse Carbine

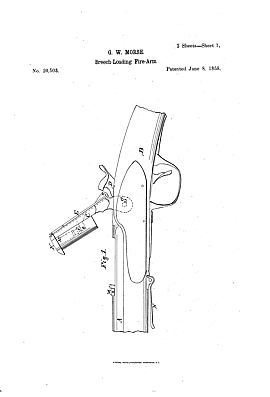

Prior to the Civil War, the US Army sought ways to alter its existing muzzle loading arms into breech loaders. The Army had even been rather forward thinking when it adopted the Hall rifle in 1819, but the Hall had its own problems, and in the four decades between the adoption of the Hall and the Civil War, several competing breech loading designs emerged. One of these designs was patented by George Morse, of Baton Rouge, in 1856 and 1858.

Morse’s patent used a breech block that raised up to expose the chamber, and the shooter could then load a metallic cartridge, a design also patented by Morse, into the gun and fire. Morse submitted his design to the US government and the Ordnance Department appropriated money to convert up to 2,000 rifles. The money ran out after fewer than 60 had been produced with another 540 partially complete. Morse secured additional funding, and Ordnance Department transferred the machinery to continue converting rifles to Harper’s Ferry in July of 1860.

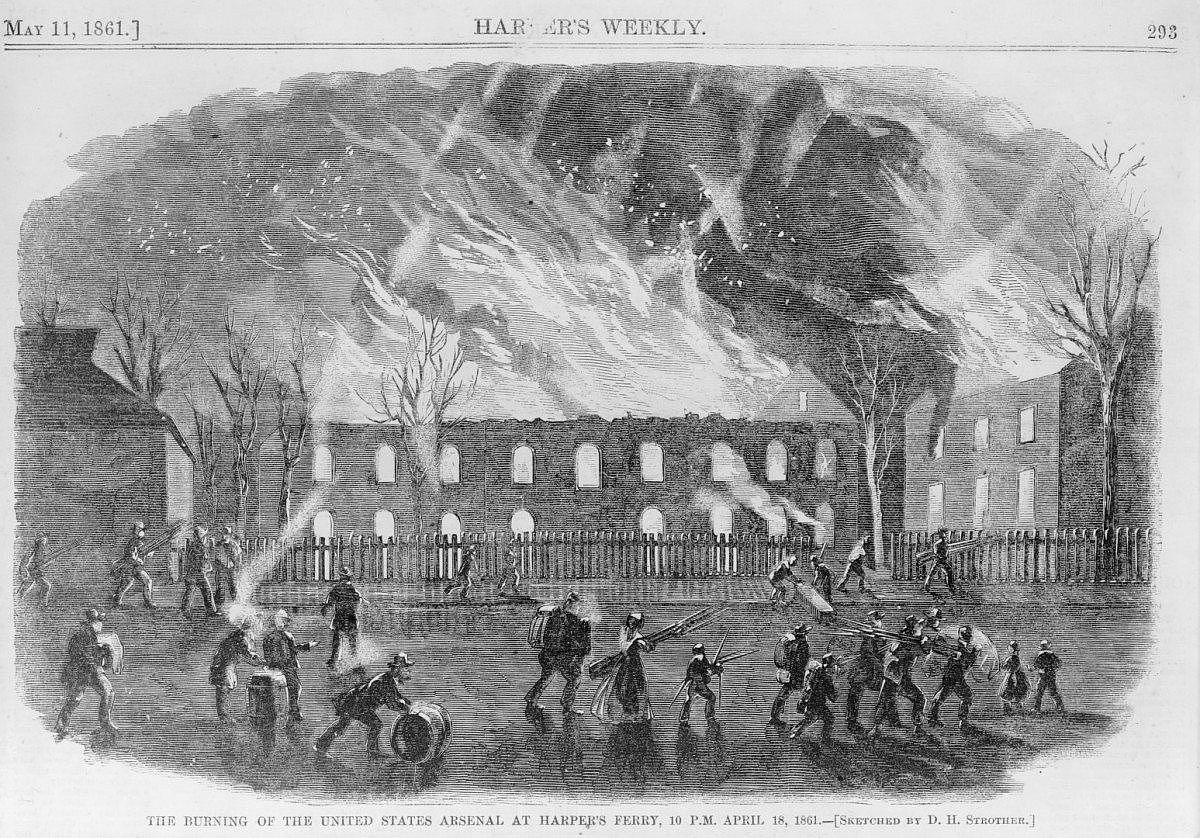

When the Civil War began, Morse sided with the Confederacy. The machinery he needed to build his rifles was still at Harper’s Ferry, which was quickly captured by Virginia Militia. The small U.S. garrison tried to destroy the arsenal before they left, but much of the equipment was still usable. The Confederacy split up the equipment between several different arsenals in the South. Morse, who by then was overseeing arsenal work in Nashville, petitioned to have his machinery moved there. The equipment had to be moved again when Nashville fell in 1862, first to Atlanta, and then to Greenville, SC.

One of Morse’s carbines was shown to a newspaper in Atlanta in December 1862, and the newspaper had high praise for the gun, but public praise did not translate into government acceptance. The Confederacy never ordered any of Morse’s breech loaders. Morse did receive a contract from the state of South Carolina for 1,000 carbines for state troops, but very few of these saw any action. The distinctive brass-framed carbines were chambered for a .50 caliber version of Morse’s centerfire brass cartridge, and the guns were issued with a unique ammunition belt that held 24 cartridges in individual tin tubes.

In contrast to the Confederacy’s struggle to field any kind of metallic cartridge breech loading arm, the Union produced large numbers of breech loaders. Spencers and Burnsides were the most common. Morse recognized the success of the Union in producing so many breech loaders, and believed that he had been the impetus for these arms. Following the Civil War, Morse unsuccessfully sued the United States for royalties on the breech loaders they had built or purchased. His lawsuit demanded five dollars for each of over 170,000 arms that he thought infringed on his pre-war patents. Despite his court loss, Morse continued working on cartridge designs for the U.S. Ordnance Department which resulted in two more cartridge patents in the 1880s. While Morse’s firearms never became widespread, the ammunition he developed was an important step in cartridge development.

Written By

Danny Michael

Danny Michael is Associate Curator (formerly Assistant Curator) of the Cody Firearms Museum. In addition to assisting with visitor inquires, researching, and writing about the collection, he also manages social media content for the Cody Firearms Museum. Danny moved to Cody from Maryland and enjoys finding ways to watch the Baltimore Orioles from Wyoming, recreational shooting, and reading about history.