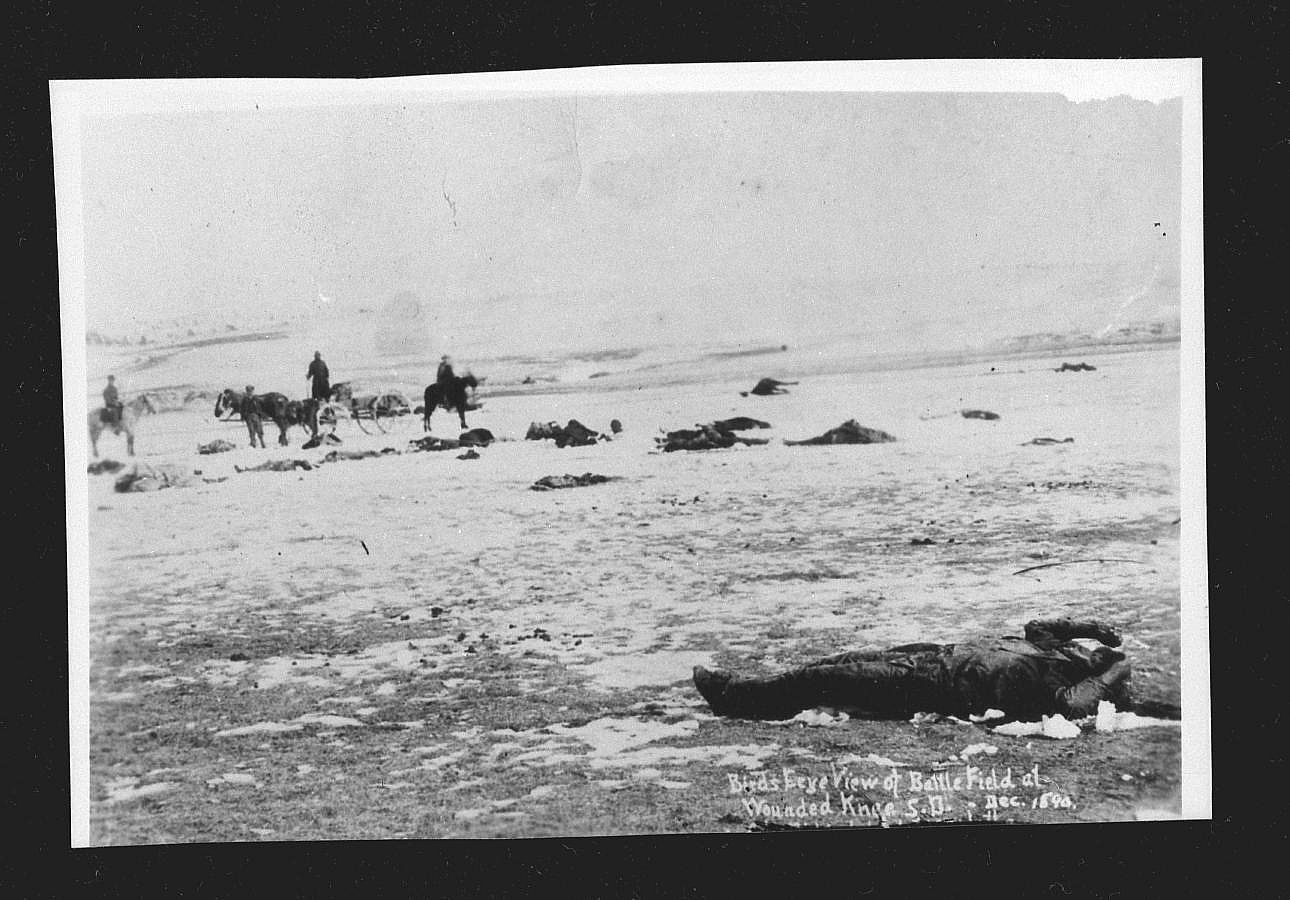

127th Remembrance of the Wounded Knee Massacre

On this day, December 29, 1890, Chief Spotted Elk’s band of Mni Coujou Lakota and 38 Hunkpapa Sioux were intercepted by the U.S. 7th Cavalry Regiment fleeing from the Standing Rock Agency to the Pine Ridge Agency. At this time, the Mni Coujou and Hunkpapa mourned the death of Chief Sitting Bull, only 14 days prior in Fort Yates, North Dakota. According to Nancy B. Rosoff and Susan Kennedy Zeller, “Sitting Bull has long been considered an obstruction to the federal government’s control of Sioux lands, and when he became an advocate of the Ghost Dance, a practice the army considered warlike, his arrest was ordered.”[1] Until his death, Sitting Bull was both leader and spiritual leader to the Hunkpapa.

Tension had rose because many Plains Tribes participated in the Ghost Dance Ceremony. The ghost dance was a “powerful, spiritual movement about hope and renewal that swept across the Plains in 1889 and 1890.”[2] Ghost Dance participants adorned themselves in clothing, which represented aspect of the natural world such as earth, sky, and spiritually significant animals such as eagles, magpies, crows, and turtles. Most ghost dance accoutrements were made of hides, pigments, muslin, and bird feathers. However, United States representatives such as Daniel Royer saw the ceremony as a means for tribes to plot warlike tactics against reservation agents. Essentially, the ceremony brightened the spirits of its participants and gave them a means of hope and encouragement.

Hide, feather, and pigment

On the day of the December 29, 14 days after Sitting Bull’s death, the Cavalry surrounded a group of Sioux participating in the Ghost Dance Ceremony. An altercation broke out between a Sioux man and a U.S. solider because he refused to give up his firearm. As a result, more than 150 men, women, and children, and, at least 20 Cavalry men, died at Wounded Knee. Following the massacre at Wounded Knee Creek, 20 soldiers were awarded the Medal of Honor.[3] The conflict essentially halted participation of the Ghost Dance. Many objects from the movement can be found in museum and private collections. The celebration of life from the ghost dance movement are carried on in the generations to survive colonialism, poverty, and genocide. The site at Wounded Knee is protected and is an area for prayer and reflection.

Notes

[1] Nancy B. Rosoff and Susan Kennedy Zeller. “Tipi” Heritage of the Great Plains,” Brooklyn Museum in Association with University of Washington Press, 2011.

[2] Emma Hansen in “Ghost Dance Dress,” Buffalo Bill Center of the West. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aiymK5TtYgQ.

[3] Wounded Knee. History.com. http://www.history.com/topics/native-american-history/wounded-knee. Accessed 29 December 2016.

Written By

Hunter Old Elk

Hunter Old Elk (Crow & Yakama) of the Plains Indian Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, grew up on the Crow Indian Reservation in Southeastern Montana. Old Elk earned a bachelor's degree in art with a focus on Native American history at Mount St. Mary’s University in Maryland. Old Elk uses museum engagement through object curation, exhibition development, social media, and education to explore the complexities of historic and contemporary Indigenous culture. She is especially inspired by the stories of Native American women who lived and thrived on the Plains. Facebook/ Instagram: @plainsindianmuseum