Inside the Lodge: Plains Indian Tipis

“The tipi, also referred to as a lodge, represents the heart of Plains culture. It facilitated each tribe’s nomadic way of life and was the center of social, religious, and creative traditions. Today’s Plains people live in modern homes, but the tipi remains an enduring architectural form, emblematic of Plains tribal identity and used by many for celebratory and ceremonial occasions.”– Nancy B. Rosoff

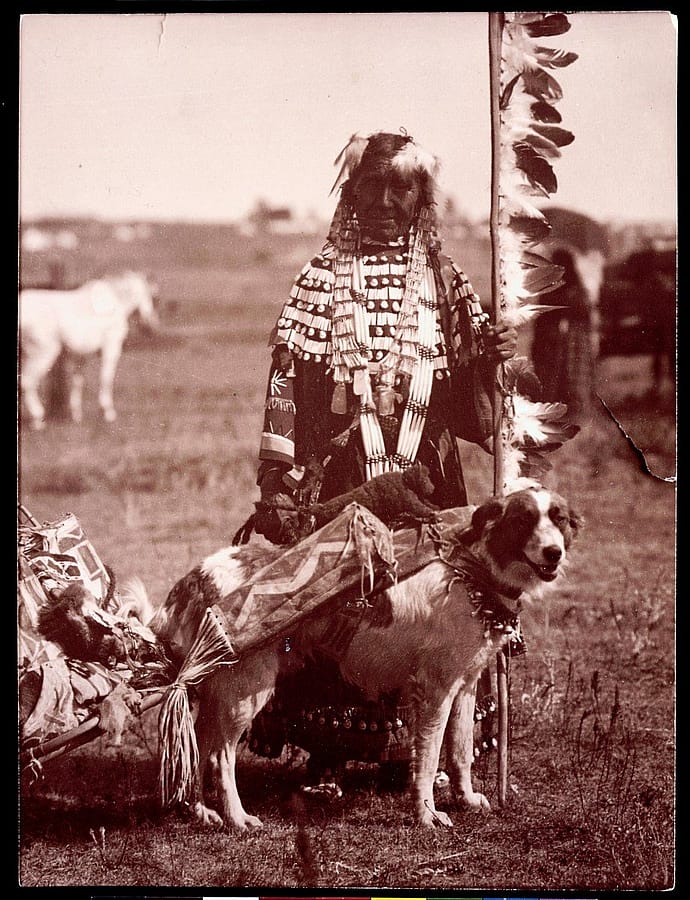

When many think of Plains culture and Native Americans, images of warriors, feather bonnets, and tipis flash through their minds. The tipi is a unique structure to the people of the Great Plains. The nomadic people, those who followed the buffalo, adapted their lodges to fit their moving lifestyles. Before the introduction of the horse, men and women relied on harnessed domestic dogs attached to travois to move their belongings. These limitations dictated the size of the tipi and how easily bands navigated the plains. Nancy B. Rosoff writes, “tipis were relatively small (about ten feet wide and high.)”[2] Horses allowed tipi dwellers to move at faster paces and consequently also allowed lodges to grow. Lodges went from “about ten feet to twenty-five feet wide and high.”[3]

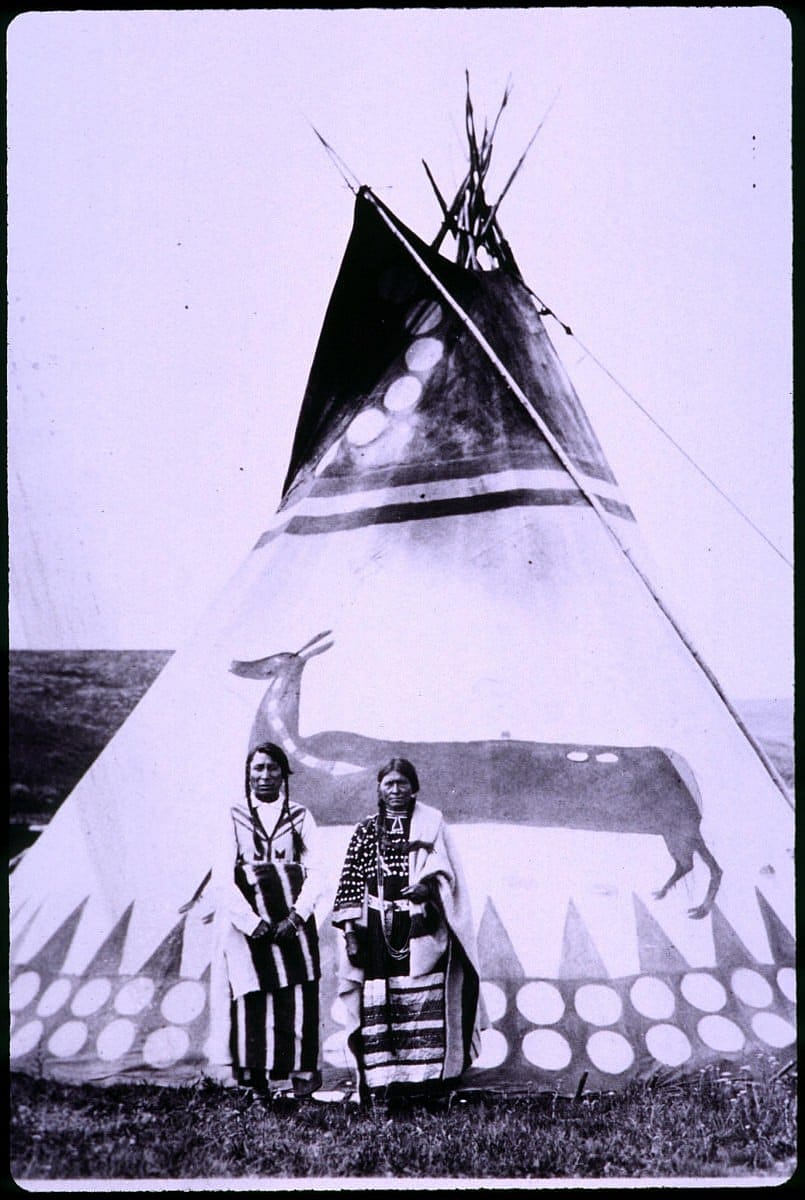

Women were tasked with the construction and assembly of tipis. Depending on the tribe, the lodge was erected from either a 3-pole or a 4-pole base with additional poles added to create the tipi frame. The base created a natural doorway and was positioned to face east to greet the sun. Wood from the tall and slender, Pinus contorta, or lodgepole pine, was preferred for tipi poles because of its resilience to weather and rot. The hide or canvas of the tipi was tied to a pole to the rear of the door and wrapped around the frame. Wood tipi pins, also called lacing pins, secured the edges and created an enclosed space. Lastly, the hide was staked down with wood and often secured with rocks. Poles were added to the flaps of tipis to support vent openings which allowed the smoke to escape the lodge when occupants lit fires. Flaps would be closed for inclement weather such as rain and snow to protect the family from moisture.

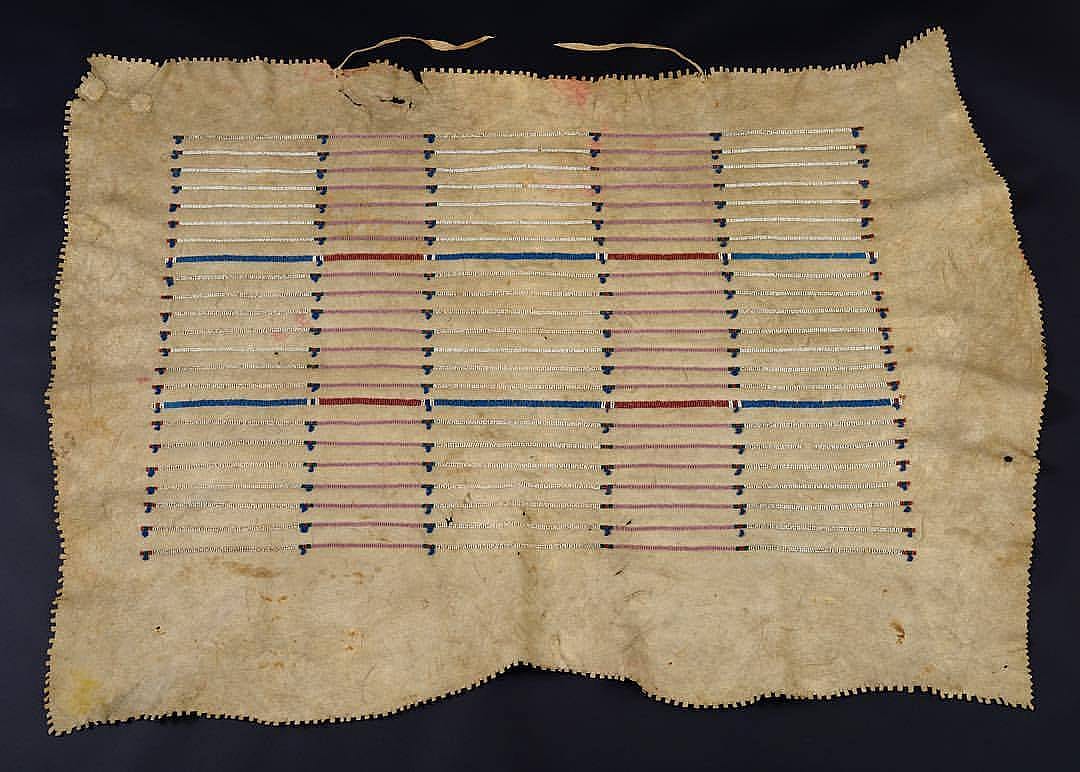

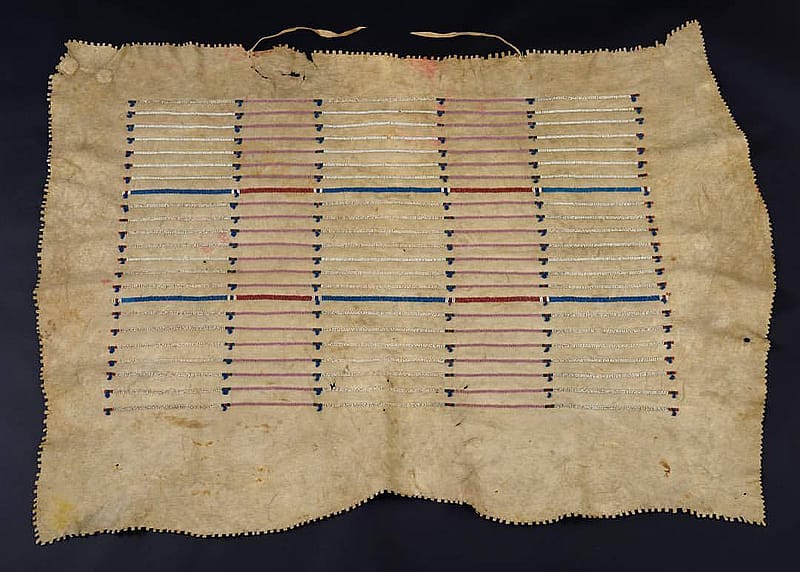

Along with the construction of the lodge, a tedious and backbreaking job, women devoted much of their time to the upkeep. Women spent many hours tending to their children and tipis. These tasks were virtuous and honorable. The Plains artistry was represented in how women and men decorated their lodges. Lodgekeepers produced objects that hung in the lodge such as tipi liners, and other decorations. Tipi liners made of materials such as tanned hides, muslin, and canvas were hung in the lodge for a couple of reasons, the first for an added layer of protection from drafts and weathers. The second being they provided privacy for occupants from shadows cast by the fire inside the lodge. Artists adorned the liners with beads, pigments, and porcupine quills. Men recorded their war experiences including coups and other acts of valor.

Some tribes have a rich culture of painting their tipis to depict their symbiotic relationship with the natural world. Illustrations of animals such as buffalo, bears, deer, elk, otters, and various birds often adorned the lodges of Blackfeet, Arapaho, Sioux, Cheyenne, and Kiowa tipis. Some lodges also depicted representations of sacred ceremonies such as the Sundance or the convening of society members. Brilliant shades of ochre and other pigments added color to the hides. Women and men used stick and bone brushes to paint detailed design work on tipis. But, not all tribes painted their tipis. Every surviving hide tipi in the Plains Indian Museum collection is a testament to the resilience of the people of the Plains. The structures, like the people, were built to withstand.

[1] Tipi: Heritage of the Great Plains, edited by Nancy B. Rosoff and Susan Kennedy Zeller (Seattle: University of Washington

Press, 2011), 3

[2] Ibid., 4

[3] Ibid., 4

Written By

Hunter Old Elk

Hunter Old Elk (Crow & Yakama) of the Plains Indian Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, grew up on the Crow Indian Reservation in Southeastern Montana. Old Elk earned a bachelor's degree in art with a focus on Native American history at Mount St. Mary’s University in Maryland. Old Elk uses museum engagement through object curation, exhibition development, social media, and education to explore the complexities of historic and contemporary Indigenous culture. She is especially inspired by the stories of Native American women who lived and thrived on the Plains. Facebook/ Instagram: @plainsindianmuseum