Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2016

Seven Days in Glasgow with Buffalo Bill, 1904, Part 2

By Tom F. Cunningham

In the previous post, Tom F. Cunningham shared stories of the weeklong stay of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in Glasgow, Scotland, in early August 1904, as part of the Wild West’s Tours of Great Britain. Using news accounts of the day, we followed the show’s activities and performances from Sunday, July 31 through Wednesday, August 4, 1904. With part two, we continue the tour for the rest of that famous week in Scotland.

Thursday, August 4, 1904

Gratifying though Wednesday’s record must have been [30,000], it was again shattered within twenty-four hours. Sixteen thousand attended Thursday afternoon and, notwithstanding torrential rain in the evening, there was a capacity crowd of eighteen thousand, with the usual receding tide of disappointed thousands. Clearly the city was experiencing an event which was truly out of the ordinary as Friday’s (August 5, 1904) Daily Record and Mail attests:

The show has the biggest seating capacity ever provided for any outdoor exhibition; but it can claim a much greater record. It has visited every capital in Europe, with the exception of St. Petersburg and Constantinople, and it has been left to the present Glasgow visit to beat all records in attendance. “No show on earth,” said one of the show’s chief officials last night, “has ever done the same business in the same number of days as we have done and are going to do in Glasgow this week. It has been phenomenal; we never anticipated anything like it.”

Other news stories developed at the same time the Wild West visited Glasgow in August 1904. Those reports include reactions to show Indians, the use of Wild West jargon in a report about a town council meeting, umbrellas, and a local Masonic Lodge.

Show Indians draw attention

The “Lorgnette” column in Thursday’s (August 4) Glasgow Evening News bore testimony to an unaccustomed presence:

The Govanhill [a neighborhood on the south side of Glasgow] boys are enjoying life just now, and the fascination of the Wild West has gripped them firmly by the throat. Even shopkeepers and other adults with leisure on their hands are not proof against the spell, and when “Lo, the poor Indian,” stalks solemnly down Cathcart Road, displaying hair which would make six bald-headed men happy, he comes in for a share of attention which probably tickles him to death, though he does not betray any emotion. The infant population of the district do not take so kindly to the noble red man. There is an erroneous impression abroad among them that he bites—with a marked preference for Govanhill babies.

Town council meeting

Seventeen years before, a cartoon in Punch magazine had satirized the visit of W.E. Gladstone to the Wild West camp in London on May 7, 1887, depicting the elder statesman as an Indian chief. This established a certain vogue for poking fun at well-known politicians in similar vein. The well-worn template was invoked once again, certain of the better-known figures from Glasgow Town Council supplying the targets on this occasion.

At the most lively and tempestuous meeting of the civic assembly at George Square “for many moons” on Thursday, May 4, the scenes of disorder presented a perceived parallel with the Wild West. Figurative tomahawks flew in the “municipal wigwam.” A Mr. Boyd “emitted several war whoops which were under-stood to be points of order.” Such was the pretext for the August 5, 1904, Evening News’s “From the Gallery” column which depicted a certain Mr. Ferguson as “A Picturesque Figure” along the same lines as Buffalo Bill. The excitable caption “On the Warpath,” while Mr. Cohen, the youngest member, found himself pilloried as “The Papoose.” The cartoonist so far forgot himself as to suggest a likeness between the energetic Mr. Burgess and Buffalo Bill’s Whirling Dervish.

Umbrellas for sale

Back at the real Wild West, as op¬posed to its George Square municipal counterfeit, the solid throng, as it departed the evening performance, was confronted by a singular piece of opportunism:

Visitors to the Wild West Show last night had one more example of Yankee enterprise, and promptness to turn everything to account. On their way out of the show, after the heavy rain which fell during the performance, and which caused a feeling of dampness even among the vast crowd, so well protected from it, they were confronted by a couple of attendants holding up a stock of umbrellas, and shouting, “Now then, remember it’s still wet outside. You’re sure to get wet. If you want to keep dry you can buy an umbrella here—two shillings for any one in the lot. Two shillings for a nice new umbrella.” (“Lorgnette” column, August 5, 1904)

Renfrew County Kilwinning Lodge

A number of members of Buffalo Bill’s staff belonged to Renfrew County Kilwinning (Masonic) Lodge No. 370, having joined during the tour of Barnum and Bailey’s Greatest Show on Earth five years earlier, and were desirous of a return visit. A special midnight meeting was therefore arranged, and they drove out to Paisley at the conclusion of the Thursday evening show. Twenty-one prospective members accompanied them, and the Masonic members duly initiated the recruits.

In addition to Buffalo Bill’s men, there were eleven other candidates, making thirty-two initiates in all. On August 6, the “Clydeside” [“Clydeside Echoes” (Glasgow Evening News)] columnist considered this something out of the ordinary and pronounced it “a record in the history of the craft.” Two days later, the Masonic column, “Square and Compasses” (Glasgow Evening News) took a dim view, considering the number of initiates excessive and at odds with the standard of decorum demanded by the occasion.

A short harmony followed, and the Wild West company returned to Glasgow in the early hours of Friday morning in exultant mood.

Friday, August 5, 1904

Such prodigious crowds inevitably drew questionable characters, and one such was Charles O’Neil, a “well-known thief,” then residing at 144 Trongate. He appeared before Bailie Taggart [municipal magistrate] at the Queen’s Park Police Court, after having been observed acting in a suspicious manner and attempting to pick pockets within the Wild West grounds. The next day, the Daily Record and Mail reported that he was sentenced to forty days imprisonment.

At the afternoon performance, Carter the Cowboy Cyclist created an even bigger sensation than he had on Monday. As he and his bicycle hung in midair, the audience saw his front wheel swerve to the right so that on touching down on the wooden staging, it ran over the edge. A thrill of horror coursed through the onlookers as man and machine fell together to the ground. Unharmed, he leapt to his feet, mounted his horse in his routine fashion, and rode off to wild applause.

In the evening, it was deemed necessary to adopt further anti-congestion measures at the entrances. [The doors were routinely opened an hour in advance of the performances, at one in the afternoon and seven in the evening respectively.] As Buffalo Bill himself told the tale, recorded in the Daily Record and Mail on August 8:

I was much touched by their [the spectators’] action on Friday night. So great was the crowd round the entrances two hours before the performance began that we decided to admit visitors from 6.30 [sic]. The seats were crowded by seven, and there was a long and wearisome wait. I walked round the arena, and the way in which the people were packed caused me some uneasiness, and the chief of police shared the feeling. But presently some one started off with a Scotch song, and the impromptu concert was kept up till the performance opened. Everybody sang with great heartiness, and the effect as heard in my tent was remarkably good.

Saturday, August 6, 1904

Thomas Lindsay

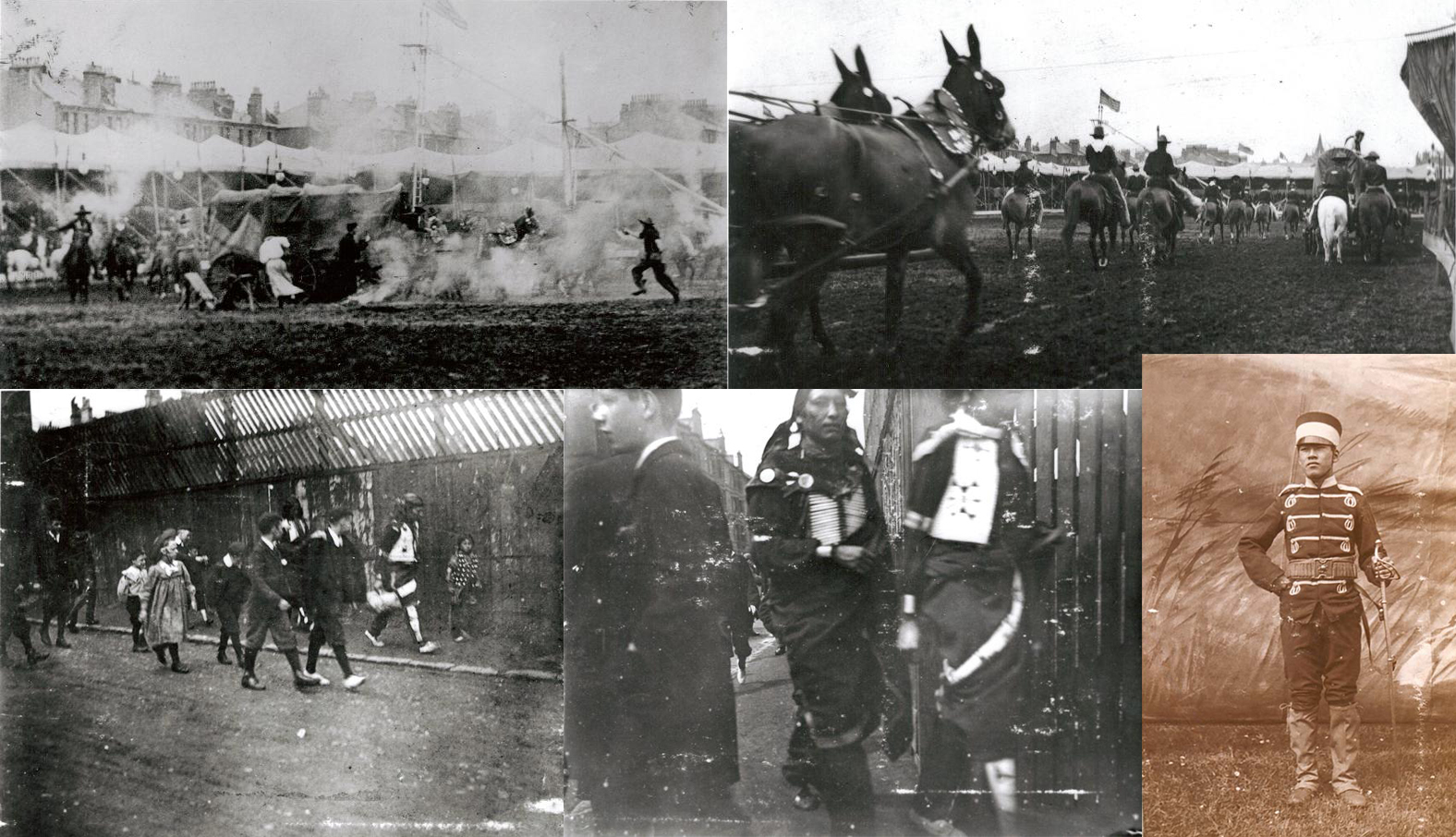

An excellent pictorial record has been preserved in the form of a collection of five photographs taken by local amateur photographer Thomas Lindsay, then aged twenty-two. Perhaps the most engaging depicts a group of youths trailing some Indians along Dixon Road. A second shows two Indians entering the show grounds. Two more capture the show actually in progress; in one the emigrant train crosses an imaginary prairie while the other records the subsequent battle scene. The fifth photograph alone, a splendid study of a member of the Imperial Japanese Cavalry, appears to have been posed.

The photographs can only have been taken at some time between Monday, August 1 and Saturday, August 6, but it is not possible to be more specific.

Glasgow health exhibition

A concurrent attraction was the Glasgow Health Exhibition, held under the auspices of the Sanitary Institute. Though Samuel Lone Bear had not been present in 1891 – 1892, his visit, from a Wild West perspective, represented a re¬turn to a scene of past glories, since the venue, the Exhibition Buildings on Duke Street, had been its home on that previous occasion. Lone Bear arrived in the morning before the exhibition officially opened. The majority of the stands were therefore still under cover, but those exhibits he did manage to see—among them the model hospital and a modern tenement—left a favorable impression upon him.

The cabinet-bath also aroused his curiosity, and he expressed his apprecia¬tion of the luxurious baths and sanitary fittings on display in the main avenue. Purveyors presented him with a sample of baby food and a box of chocolates for the children at home. Lone Bear expressed his regret that he was obliged to leave early in order to be back at the Wild West in time for the afternoon performance, and that he would not therefore have the opportunity of seeing the exhibition in full swing or of enjoying the Corporation Band and the Band of the Scottish Rifles musical programs.

Indians and children

The “Lorgnette” column also offered a few observations concerning the manners and habits of the Indians:

To return to “The Poor Indians.” One feature that has been brought out prominently during the week is their kindly disposition wherever children are concerned. They display the greatest interest in any baby in arms they chance to see, and are all eagerness to have a closer inspection. The fond mother usually, however, while flattered, seems to shrink from encouraging their fond curiosity. Whenever one of [them] goes out to give her own little ones an airing, she makes them shake hands with the youngsters nearest them, and the little Indians do so, all smiles. Yesterday, during the war dance, one of the little fellows danced into the arena, dressed in all his Wild West finery, and waving gleefully a balloon fixed on a cane, which had been presented to him by an admiring lady.

Buffalo Bill’s farewell to Glasgow

A total of 175,000 people had seen the show in twelve performances and net profits for the week were estimated at between £12,000 and £15,000, according to the “Lorgnette” column of August 12. Glasgow can rightly count itself as one of the Wild West’s spiritual homes; in the long history of the show, nothing like it would ever be seen again.

Not one single accident had befallen the spectators since, as Buffalo Bill himself acknowledged, they had been orderly in their conduct and had proven amenable to the directions of the ushers.

At the conclusion of the evening performance, Buffalo Bill fired a parting shot to waiting reporters:

Please express through your journal to the citizens of Glasgow my heartiest thanks for and profound appreciation of the magnificent support they gave us during the week. Glasgow has beaten all records for attendances on this side of the Atlantic, and comes second to the Chicago World’s Fair record in 1893. You may take it from this that I am more than satisfied. I expected much from Glasgow, but not so much.

The fame of Buffalo Bill’s great Scottish successes was heard as far away as western Canada as in this clipping from the Manitoba Free Press on October 1, 1904, a fitting summary of the Wild West’s appearance in Glasgow:

At Glasgow especially the crowds were large. So large that they have been exceeded only by those of Chicago. So Buffalo Bill looks to Glasgow with respect, and Glasgow remembers him as the man who provided the largest and most realistic entertainment that ever visited the city.

About the author

For the last two decades and more, Tom F. Cunningham has pursued an intensive study of Native American history with particular emphasis on connections with Scotland. He is the author of The Diamond’s Ace—Scotland and the Native Americans, and Your Fathers the Ghosts—Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in Scotland. He’s conducted research at the Center of the West and is a regular con¬tributor to the Papers of William F. Cody. He currently administers the Scottish National Buffalo Bill Archive, www.snbba. co.uk, dedicated to telling the story of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in Scotland.

Post 274