Seven Days in Glasgow with Buffalo Bill, 1904, Part 1 – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall 2015

Seven Days in Glasgow with Buffalo Bill, 1904, Part 1

By Tom F. Cunningham

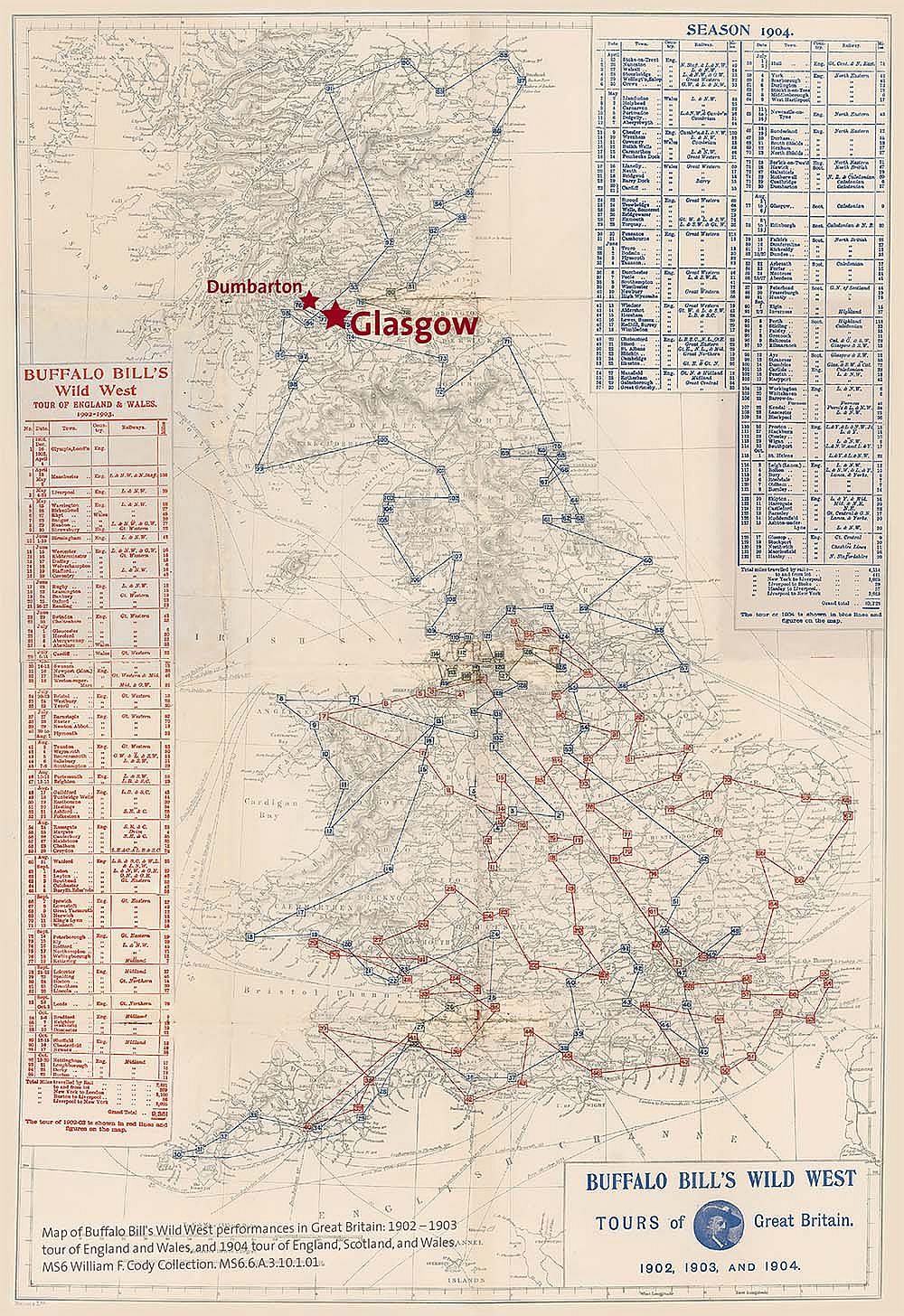

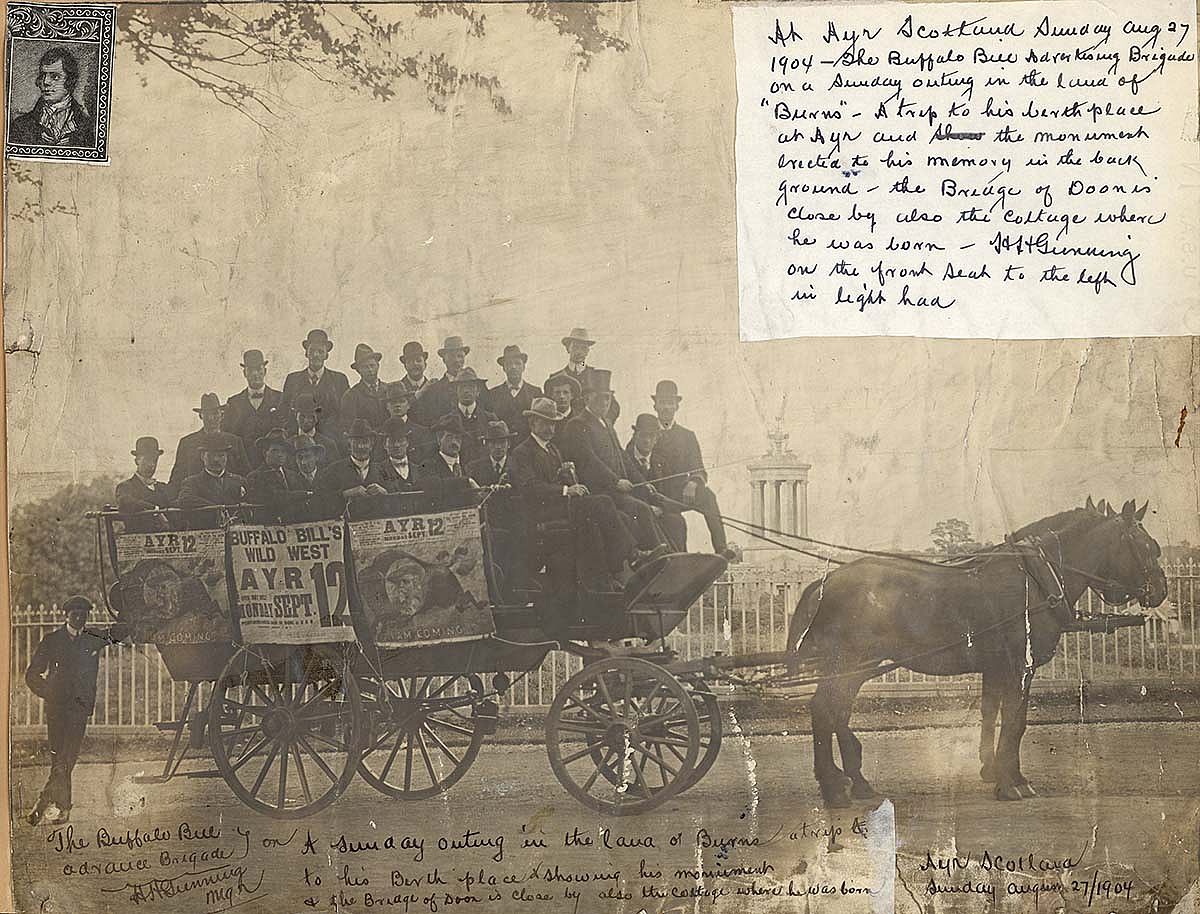

A Scottish resident and a graduate of Glasgow University, it seems fitting that Tom F. Cunningham would have an affinity for the visits of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West to Glasgow (1891 – 1892, and 1904). Here, Cunningham chronicles the 1904 visit day by day, July 31 – August 6, 1904, a journal approach complete with media coverage and unique goings-on of each day.

Sunday, July 31, 1904

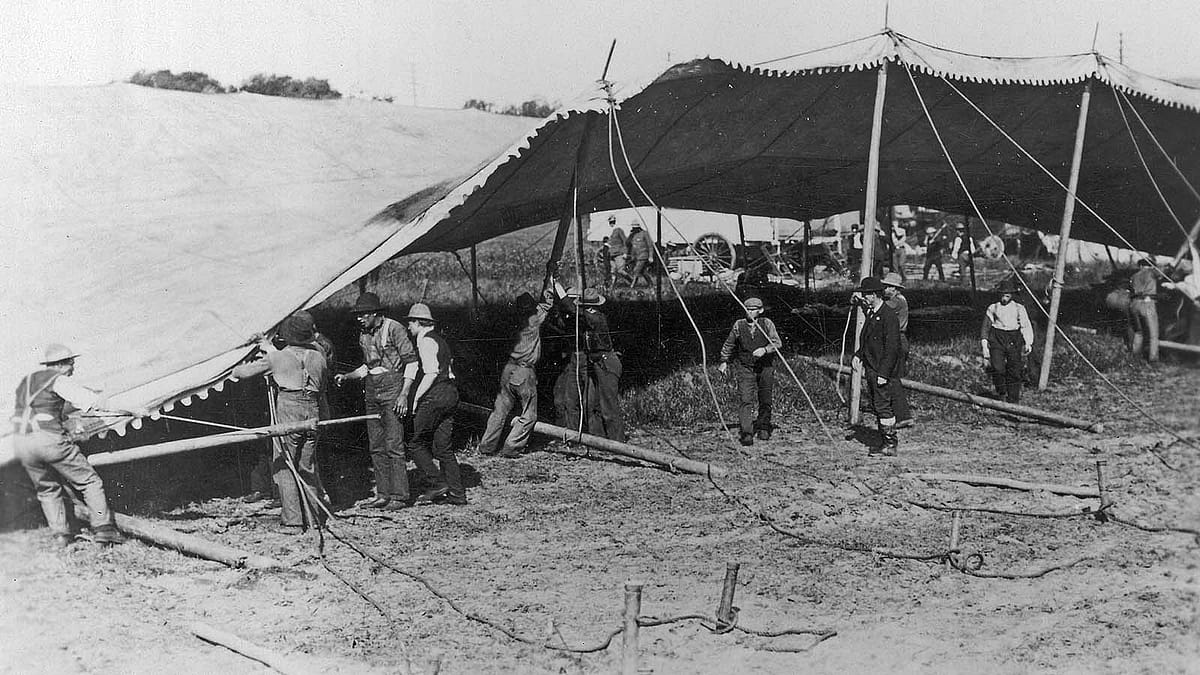

Following their departure from Dumbarton, a few miles to the west, the first of Buffalo Bill’s special trains steamed into the Caledonian Railway’s Gushetfaulds goods station in Glasgow’s Gorbals district on the south bank of the River Clyde. It was three-thirty in the morning; the remaining trains arrived shortly thereafter and unloading commenced at five. By seven-thirty, the whole impedimenta were in place and breakfast had been served, leaving the company free to enjoy its customary day of rest.

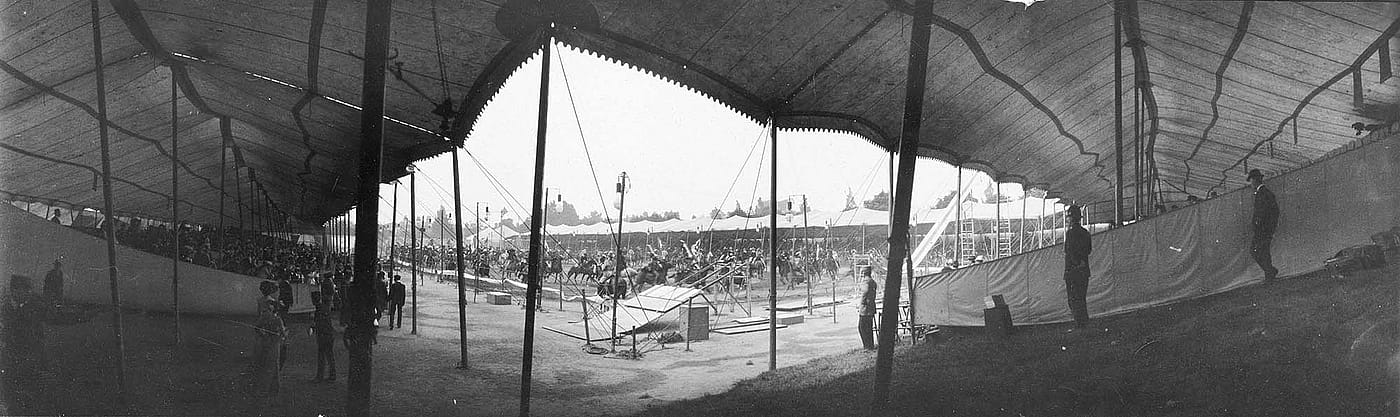

The venue on this occasion was the Third Lanarkshire Rifle Volunteers Drill Ground. Over the course of the day, spectators in their thousands laid siege to the encampment. But, peering through the gaps in the barricade, which in those days surrounded what was known locally as the “Baun Park,” they had to content themselves with occasional glimpses of the proceedings within.

The Stars and Stripes fluttered gaily over the show grounds that afternoon, as a large body of pressmen, attending by invitation, entered. There they caught sight of the booking office with the main entrance to the arena a little farther on. After partaking of dinner in the dining tent, Wild West agents gave the party a guided tour of the establishment, including the various living quarters, the stables, two American muzzle-loading artillery pieces, and the Deadwood Stage. Messrs. Burke, Wells, and Small, Buffalo Bill’s press agents, explained the workings of the organization to them and effected introductions to Johnnie Baker and other celebrities.

There followed a visit to Colonel Cody’s personal tent, where the reporters found him enjoying the society of his accustomed companion, Chief Iron Tail, with an interpreter also on hand. The Glasgow Evening Times representative poetically delineated the tent’s location in the newspaper’s August 1 edition:

Buffalo Bill’s neat tent…looks out on the Cathkin Hills, which if lacking the magnificence of the Rockies, is not without pictorial charm under the August sun.

The old Indian’s yellow shirt, with points of red, together with his gaudy blanket, contrasted strangely with the sober suits of the Glaswegians. The pressmen, uncomprehending, returned his greeting of “hau kola,” which was then translated to them as “hello friend(s).” Responding to a word from Buffalo Bill, the venerable chief briefly absented himself and returned with a long-stemmed wooden pipe. He conducted a smoking ceremony in honour of the visitors, lighting his pipe and passing it to each of them in turn. The tobacco’s odour invoked memories of the real Wild West and set Buffalo Bill talking of the old days with affectionate regret.

The normally solid and reliable “Clydeside Echoes” columnist in the Glasgow Evening News on the same day facetiously implied that the longhaired members of the party felt a certain nervousness for their scalps. However, the Daily Record and Mail recorded an altogether more creditable impression in its August 1 edition, writing, “Thus was the calumet of peace smoked, and nothing but brotherliness and geniality prevailed between the white men and the red.”

Monday, August 1, 1904

More than a dozen years had passed since Buffalo Bill’s previous visit, and for some it was already a distant memory. Indeed, at least four correspondents wrote to the “Voice of the People” column in the Evening News asking when and where Buffalo Bill had last appeared in the city. The August 1 issue duly provided the necessary clarification.

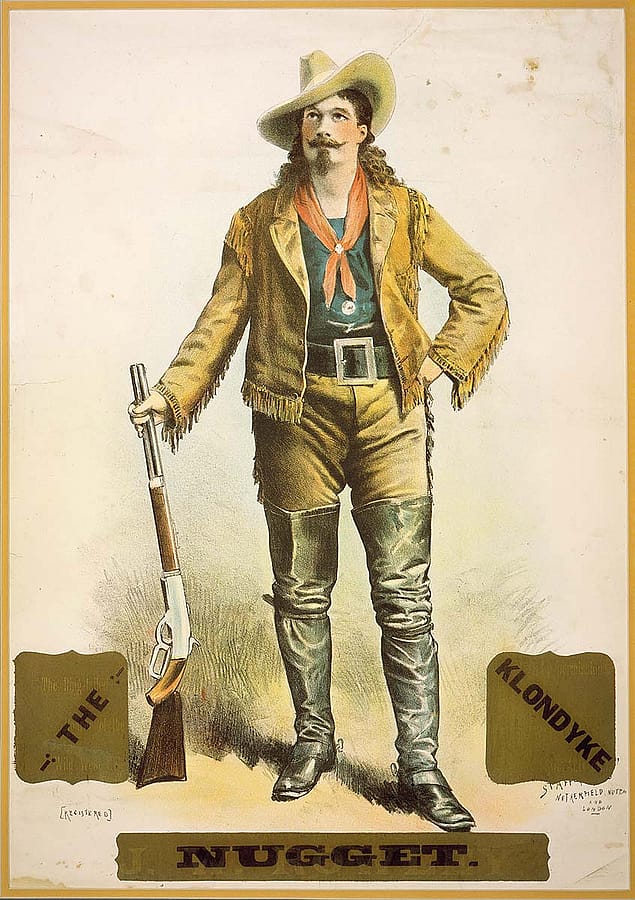

The Klondyke Nugget

When the following notice for the play The Klondyke Nugget appeared on August 1 in the Evening Times, it may be taken that the Glasgow public was understandably confused at the mention of another “Famous Cody” appearing across town with cowboys, ponies, and “sensational Wild West drama”:

Nightly Appearance of the Famous

S.F. Cody

And his COWBOYS and Specially trained ponies

With A Powerful American Combination,

Depicting the Sensational Wild West Drama

THE KLONDYKE NUGGET.

The performance was advertised to take place at the Royal Princess’s Theater every evening of the week beginning August 1, i.e. in the same week that Buffalo Bill was appearing elsewhere on the South Side.

What is on the surface an impossible coincidence is resolved by the fact that “the other Cody” had been born Franklin Samuel Cowdery. In common with the man upon whom he closely modeled himself, Cowdery was a native of Iowa. He had followed the Buffalo Bill phenomenon across the Atlantic and carved out a career for himself in Great Britain as a Wild West cowboy, trading upon the falsehood that he was related to Buffalo Bill in some way. On one infamous occasion in 1891, his attempts to pass himself off as Colonel Cody’s son had provoked litigation according to the Evening Express, July 4, 1891. His stage show was essentially a family affair, and his adopted sons gave exhibitions of shooting at every performance. The sole “Indian” part in the show—that of a “chief” named Waco— was in fact acquitted by young Leon Cody.

In this earlier phase of his career, “Colonel S.F. Cody” can be accounted as no more than a crankish non-entity. Astonishingly, however, after abandoning his Wild West pretensions, he accomplished merited fame as a pioneering aviator and, in 1908, became the first man to achieve powered flight in Great Britain. He died in a flying accident near Farnborough in 1913. However, memories of his Wild West days persisted, and both during his lifetime and since, he has been very frequently conflated with Buffalo Bill. (Learn more about Samuel Franklin Cody in Lynn Houze’s article in Points West Online.

Shooting Galleries

During this time, Glasgow’s shooting galleries experienced a sudden boom in business. In the August 2 “Clydeside Echoes,” the writer suggests the popularity was probably due to the presence of Buffalo Bill:

A man from Govan spent the greater part of a week’s wages last night in bombarding one of the little glass balls supported by a spray of water. At the end of the fusillade it still bobbed with the most aggravating serenity, and continued to bob until the exasperated marksman scooped a half-used “chow” from among his back teeth and smacked the ball dead at the first try.

Carter the Cowboy Cyclist

Once in Glasgow, Buffalo Bill’s first exhibition of the 1904 season commenced at two o’clock on the afternoon of August 1. In its review of the performance the next day, the Evening News carried this powerful endorsement:

Seldom does a show of the magnitude of Buffalo Bill’s strike Glasgow. When one does, there is a general inclination to make comparisons. In the case of the Wild West, especially when one considers the class of entertainment provided, no comparison was admissible. It is a show which stands unrivalled and alone.

The event drew a relatively modest total of 11,000 spectators, but as the week wore on, an unstoppable momentum asserted itself as a dominant theme of almost unparalleled success was quickly established.

The performance of “Carter the Cowboy Cyclist” added a heightened sense of drama. Strong winds forced him to reconsider making his leap through space, but after a few minutes’ delay—during which he reduced his audience to a state of nervous tension—the cyclist completed the stunt without a hitch, much to the relief of all.

Tuesday, August 2, 1904

If the show was phenomenal, then so, too, was the response from the Glasgow public. On Tuesday evening, there was a capacity crowd. The popular parts of the arena sold out shortly after 7 p.m., and approximately 5,000 disappointed spectators were turned away.

Wednesday, August 3, 1904

Records established on Tuesday soon gave way to an even stronger demand for tickets on Wednesday. The August 4 Evening Times carried a stark testimony to the show’s overwhelming popularity, writing, “Buffalo Bill’s show had the biggest attendance yesterday in its record of twenty-one years of performances.”

Record Attendance

In the Wild West’s two performances of the day, thirty thousand spectators attended. Due to the public response on Monday and Tuesday evenings, organizers considered it necessary—for the first time in the history of the show—to provide accommodation for an additional four thousand spectators, raising the total number of seats to eighteen thousand for Wednesday. Even this modified arrangement proved hopelessly inadequate. All night long, in addition to the departing thousands, large crowds with the hunger of wolves in their eyes laid siege to every entrance.

The Glasgow newspapers estimated that if Wednesday evening’s audience stood shoulder to shoulder, the line would extend ten-and-a-half miles. There was, however, an inevitable downside to this spectacular success, and few would have taken issue with the “Clydeside Echoes” columnist’s August 4 assessment of the unedifying scramble:

It is the conviction of many who have not yet reached the interior that the wildest part of the Wild West Show is the charge of the public upon the ticket offices and the entrances.

In the August 1904 column “The Voice of the People,” the writer sounded a further negative note for this week of superlatives—an account that raised widespread concerns:

We have received a number of letters regarding the crush and difficulty of getting tickets at Buffalo Bill’s show last night. The writers more or less condemn the management for lack of adequate arrangements, but it is obvious that even with the most perfect arrangements possible, 18,000 people cannot get into any enclosure, and especially a temporary enclosure, without some discomfort. The publication of the letters, some of them in excited terms, would serve no good purpose. Under the circumstances, what is really wanted is a little more patience and order on the part of those who are anxious to get into the show.

The week in Glasgow heads into Thursday’s activities in the part two of Seven Days in Glasgow with Buffalo Bill.

About the author

For the last two decades and more, Tom F. Cunningham has pursued an intensive study of Native American history with particular emphasis on connections with Scotland. He is the author of The Diamond’s Ace—Scotland and the Native Americans, and Your Fathers the Ghosts—Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in Scotland. He’s conducted research at the Center of the West and is a regular contributor to the Papers of William F. Cody. He currently administers the Scottish National Buffalo Bill Archive, www.snbba.co.uk, dedicated to telling the story of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in Scotland.

Post 273

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.