Samuel Franklin Cody and William F. Cody – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2011

A Case of Mistaken Identity: Samuel Franklin Cody and William F. Cody

By Lynn Johnson Houze

Turn back the years, all the way back to early 1891, and try to imagine how excited you would be to attend a performance of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West.

Now, imagine how badly you would feel when you found out that the show you were viewing was a “knockoff” of the original, and that “Buffalo Bill” was a “wannabe,” merely a look-alike. He purposely confused the public into thinking that he, Samuel Franklin Cody, was the William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, the famous scout, buffalo hunter, showman, and entrepreneur. To many it must have been a disappointing experience, but others enjoyed the performance, never realizing that they hadn’t seen the real Buffalo Bill and his Wild West.

Everything about the life of S.F. Cody, born Franklin Samuel Cowdery, was confusing and misleading. For more than a hundred years, it was believed that he was born in Birdville, Texas, in 1861. Only in the past ten years—thanks to author Garry Jenkins in his book, Colonel Cody and the Flying Cathedral—have we learned that Cody’s real birthplace was Davenport, Iowa, where he was born in 1867. Perhaps S.F. felt that a Texas birthplace gave him more credence as a man of the frontier, though Iowa was certainly fine for the real “Buffalo Bill,” who was born in Le Claire in 1846.

Leaving home by 1881, S.F. Cody tried various occupations—according to his stories—including participating in one of the longest cattle drives from Texas to Montana, as well as the Klondike gold rush. While it can’t be verified that he did either, he did become an excellent horseman along the way and definitely loved the cowboy life. By the mid-1880s, S.F. was working as a “mustanger,” a cowboy who rounded up wild horses on the Plains, and then “broke” them so they could be sold to ranchers and cattlemen.

In spring 1888, Cody joined Adam Forepaugh’s New and Greatest All-Feature Show and Wild West Combination as a sharpshooter. The main star was Doc Carver, who had been Buffalo Bill’s partner in the first year (1883) of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Prairie Exhibition, and Rocky Mountain Show. When Carver departed the Forepaugh show in the fall of ’88, S.F. claimed that Forepaugh gave him the title of “Captain Cody: King of the Cowboys.” However, the latter part of that title was already in use by Buck Taylor—hero of a series of dime novels by Prentiss Ingraham—and, beginning in 1885, the “King of the Cowboys” for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. S.F. Cody’s claim to that title has not been verified.

It was during this season, while performing with the Forepaugh show in Pennsylvania, that S.F. met Maud Lee, and after obtaining her father’s permission, married her the following year. Whether to impress his new wife, her family, or both, Cody began to claim kinship to Buffalo Bill during this time. Due to Forepaugh’s death in 1890 and the dissolution of his show, among other things, S.F. decided to travel to England to see if he, and ultimately Maud, would enjoy greater acceptance by the British public as western entertainers than they had in America. The popularity of Buffalo Bill and his Wild West exhibition in 1887–1888 certainly had indicated that England was enthralled with the American West.

After several appearances with theatrical productions, S.F. and Maud, who had joined him in England by then, were hired by Frank Hall in December 1890. A producer of burlesque

shows, Hall picked the two to appear in a production designed to lampoon Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. They appeared as “Buffalo Bill” and “Any O’Klay,” according to Jerry Kuntz in his newly-released biography of the couple titled A Pair of Shootists: The Wild West Story of S.F. Cody and Maud Lee, published by the University of Oklahoma Press in 2010. It was this show that first sought to confuse the public into thinking that they were seeing Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, which had just closed for the season two months earlier in Germany. Theoretically, it was therefore possible for “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West” to be in London at this time—although, of course, it wasn’t.

In fact, William F. Cody filed a lawsuit against Hall to prevent the use of “Wild West,” a term he had protected over the years from use by Doc Carver, Adam Forepaugh, and others. Nevertheless, the impersonators continued to confuse the public by appearing in a drama titled The Wild West with S.F. billed as the son of William F. Cody and Maud billed as his sister, Lillian, thus representing themselves as Buffalo Bill’s children! On November 2, 1891, the lawsuit finally came to trial and was won by Frank Albert Hughes, one of the producers using the term “Wild West,” probably because Buffalo Bill’s representatives did not show up, according to Kuntz.

For whatever reason, or reasons, the marriage of Maud and S.F. became strained, and they separated during their next theatrical endeavor, Germania. In the shooting act, Cody replaced Maud with their mutual friend Lela King. In fact, as soon as the drama closed, Maud Lee returned to Pennsylvania and to her parents’ home, never to see her husband again. She subsequently was diagnosed with both schizophrenia and drug (morphine) addiction from which she never recovered. She did have periods of remission and tried to continue with her career as a sharpshooter and horseback rider, both extremely dangerous pursuits for someone in her condition.

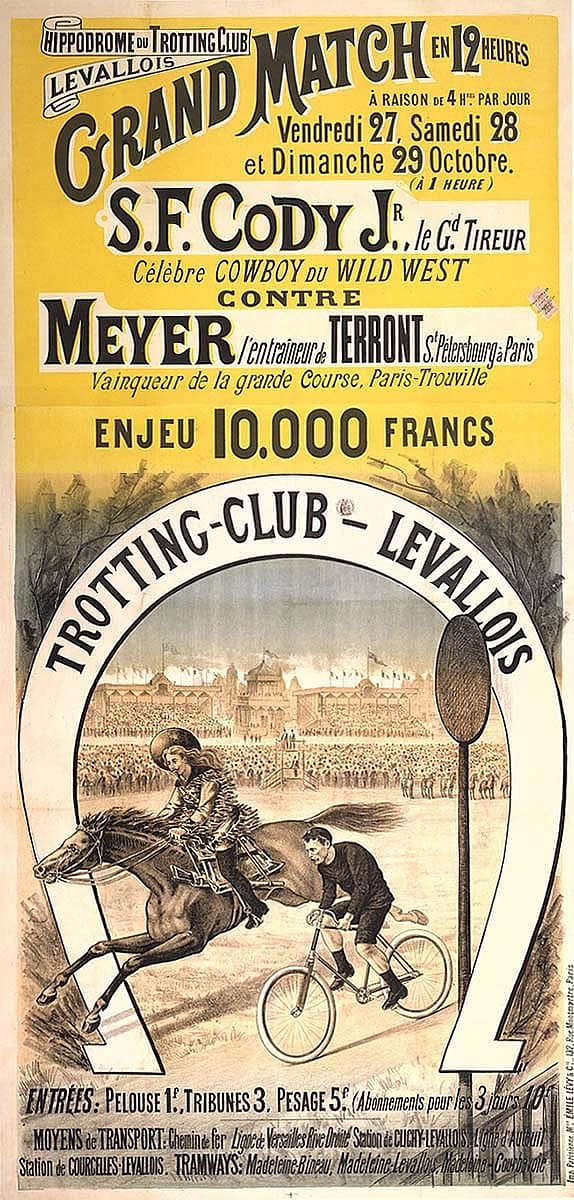

In the meantime, S.F. continued his shooting act and became so close with King that he moved in with her and her two sons, so that they were soon a “family.” By 1892, the family was traveling to France and other European countries putting on their wild west-type exhibitions. S.F. also became involved with bicycle races against horses, which were popular with the public but not with the cycling world, according to Cycling Magazine. Other acts that Cody included were chariot races, wrestling matches, and dramatic western scenes.

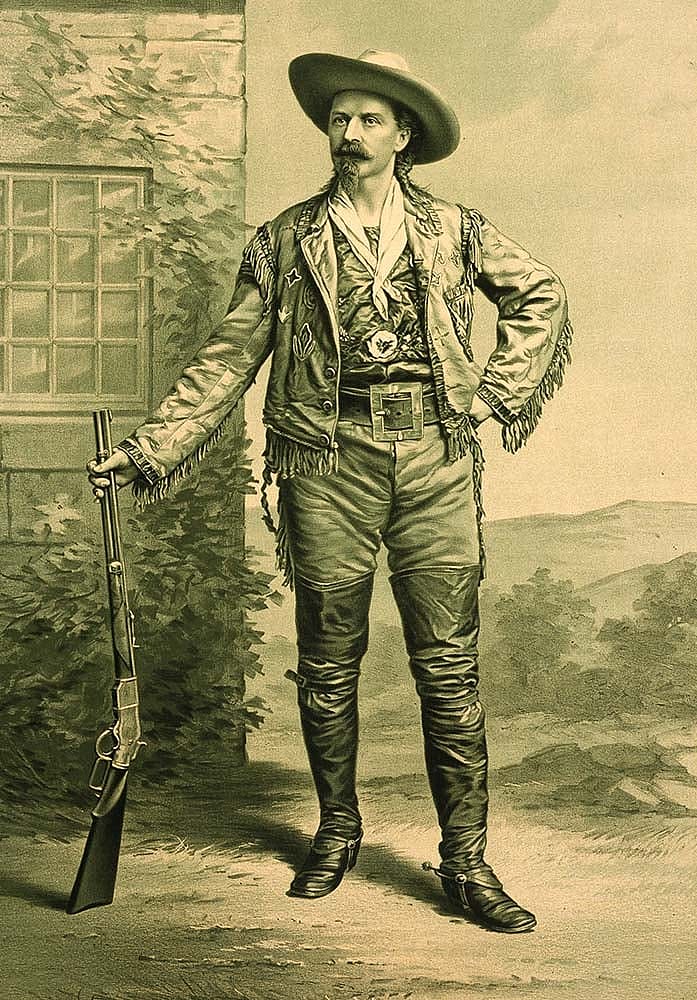

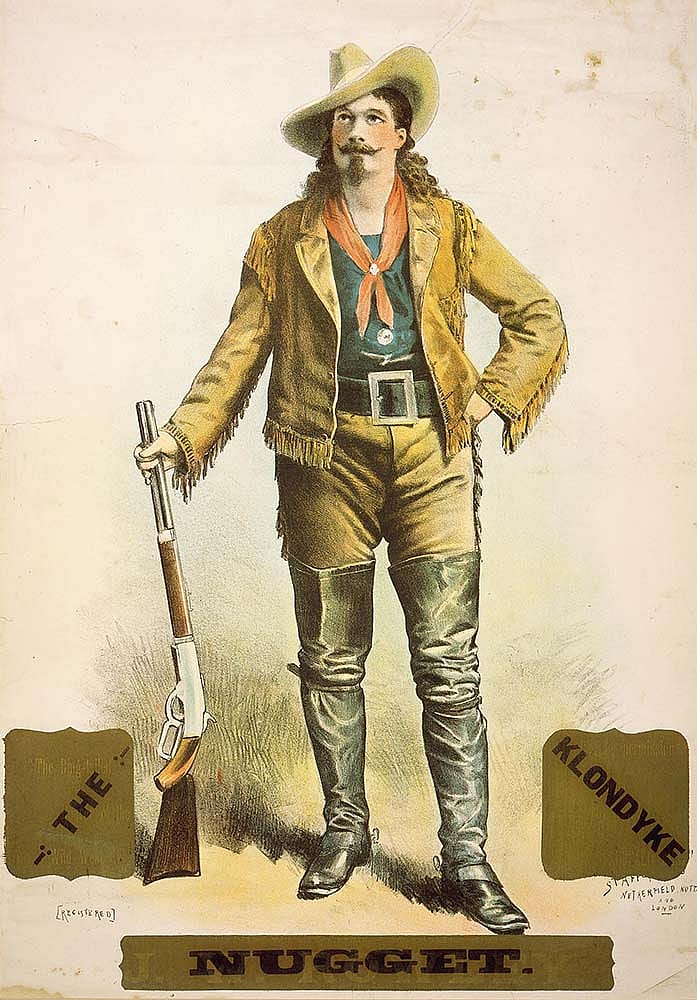

By 1898, S.F. became interested in melodramas and produced a five-act play he called The Klondike Nugget, capitalizing on the gold rush in the Yukon Territory that began a year earlier. While this aspect of his invented autobiography lent authenticity to the plot, it seems unlikely that he ever travelled to Alaska, let alone prospected for gold there. In this play, the extravagant set designs depict everything from a mine shaft to a collapsing bridge. According to author Kuntz, the audience was enthralled by the sets but probably cared little for the plot. To publicize this play, Cody created a poster patterned after one of William F. Cody’s posters for the Wild West by replacing Buffalo Bill’s head with his own. S.F. even had the audacity to stage The Klondike Nugget in some of the same towns and at the same time where Buffalo Bill’s Wild West was appearing.

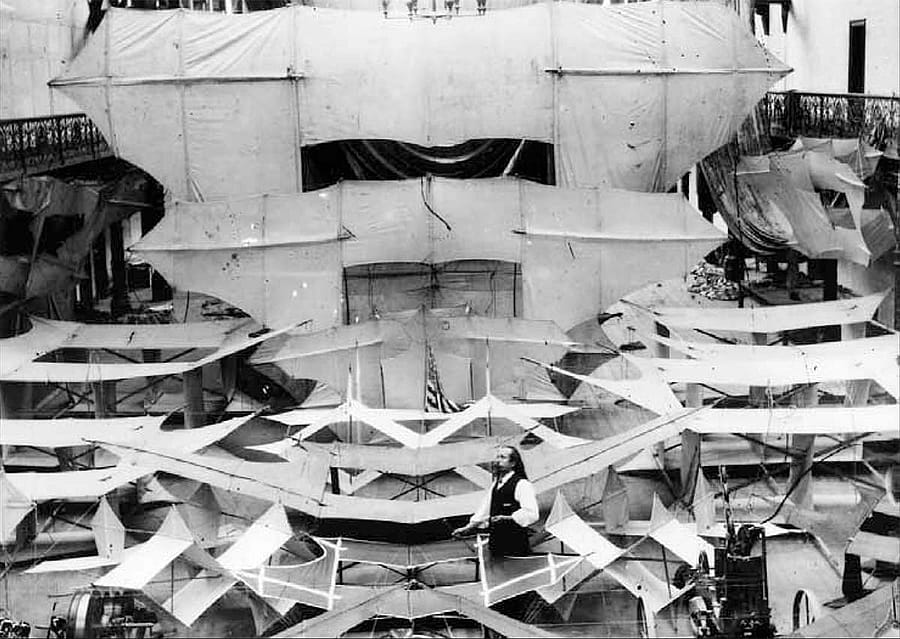

S.F. continued to dress like Buffalo Bill at least until 1905, and by that time, King George V addressed him as “Colonel,” thereby—in Cody’s mind, at least—entitling him to use that honorary title. Yet, The Klondike Nugget was really S.F.’s last overt attempt to purposely confuse the public into thinking that he was William F. Cody. S.F.’s consuming interest was in kite flying and the lifting of heavy objects by balloons, which he’d been using as targets in his shooting act for several years. He began working on a system that combined the principles of both kite flying and hot air balloons to create a “man-lifting kite system,” something other hopeful inventors of flying machines were working on in both Europe and the United States.

It is interesting to note that hot air balloons had been around for over a century. The first hot air balloon ride with “passengers” on board took place in France in 1783 when the Montgolfier Brothers put goats in a basket hanging below the balloon. At the time, it was deemed too dangerous for people; so the goats were sent airborne and returned safely to earth.

In February 1905, S.F. was hired as a “kiting instructor” for the British Army Royal Engineers Balloon Factory in Aldershot, England, leaving behind forever his wild west career. He was successful as an aviation pioneer, becoming the first person in Great Britain to achieve sustained, powered flight, and also acquired a British patent for his variation of the double-cell box kite. He even became a British citizen in 1909. His interest in aviation led S.F. to develop and fly six versions of kites and biplanes, including one known as the “Flying Cathedral.” His love of aviation eventually led to his death when his plane crashed near Farnborough, England, not too far from the English Channel, on August 7, 1913.

The confusion between Samuel Franklin Cody and William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody did not end with their deaths but continues to this day. From time to time, visitors to the Buffalo Bill Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West will ask why Buffalo Bill’s aviation career isn’t covered in our exhibits. The answer, of course, is that William F. Cody was not an aviator and many believe that he may have even been leery of flying.

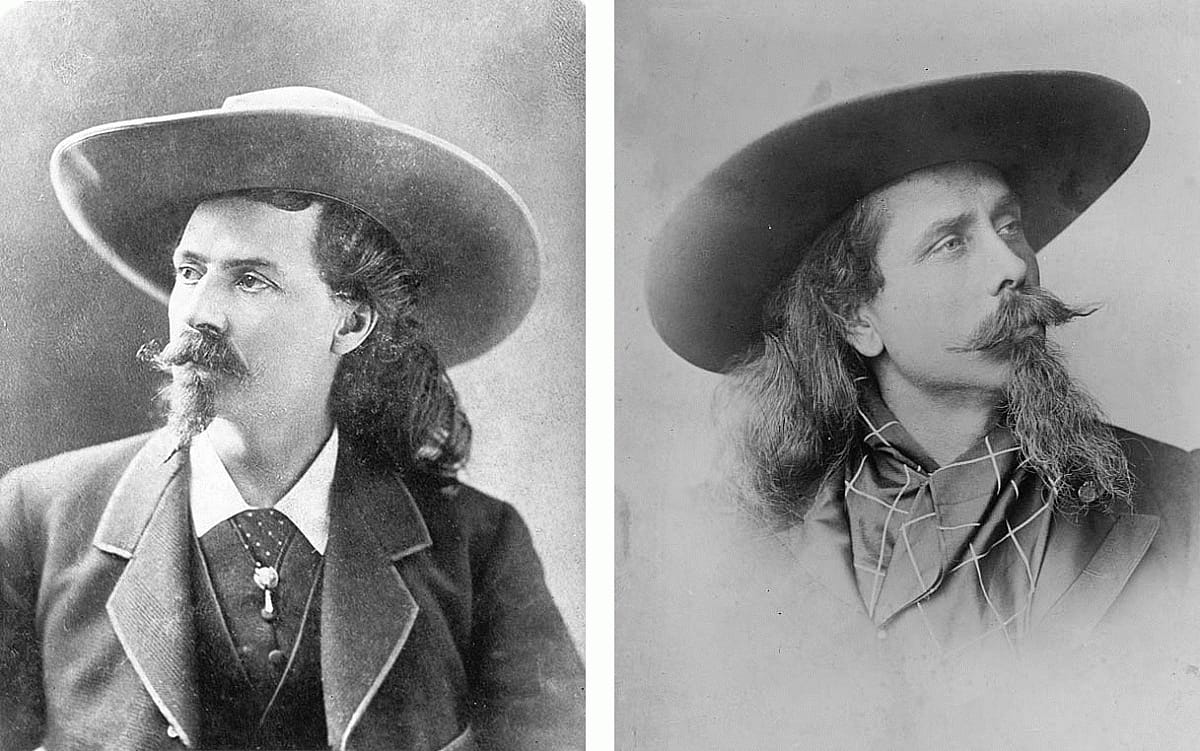

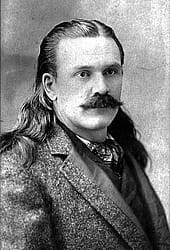

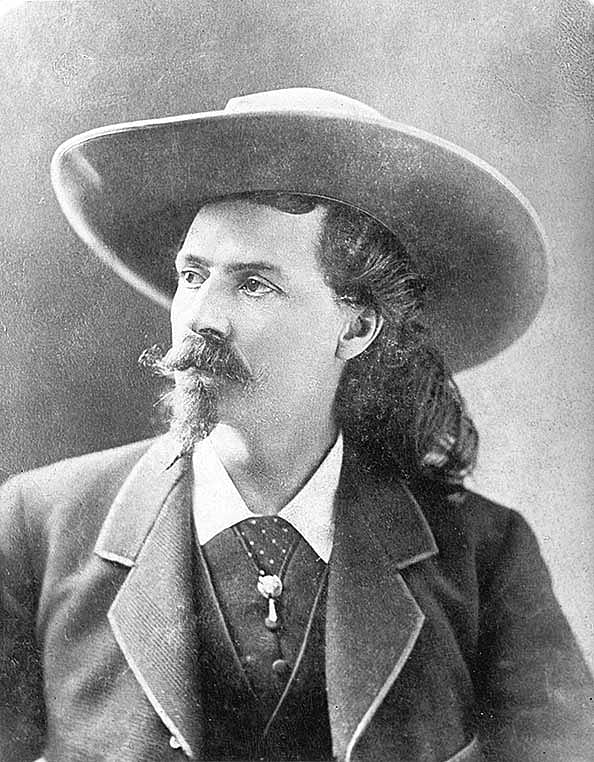

William F. Cody, ca 1876. MS 6 William F. Cody Collection. P.6.134

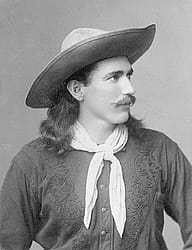

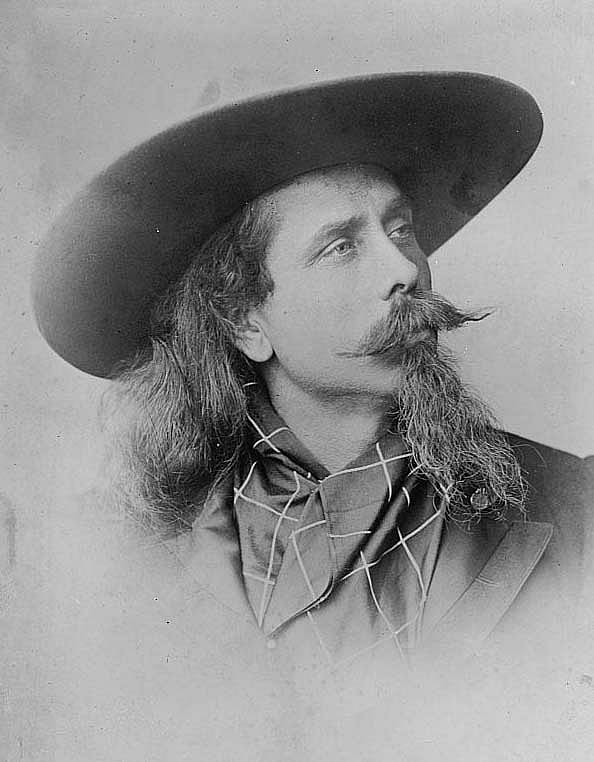

Samuel F. Cody, 1909. George Grantham Bain Collection, United States Library of Congress. LC-DIG-ggbain-03572

About the author

Lynn J. Houze served as Curatorial Assistant for the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s Buffalo Bill Museum from 2000 until her retirement from the position in early 2013; there she delved daily into William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody’s life in the Cody, Wyoming, area as well as with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. Before that she worked as Assistant Curator of the Park County Historical Society Archives. She is currently Director and Curator the Cody Heritage Museum.

She belongs to the local historical society, the Wyoming State Historical Society, and several other historic-minded organizations. In 1996, she was part of the Cody Centennial Committee which coordinated the 100th anniversary of the founding of the town, the occasion of the release of Houze’s first book which she co-authored on the history of Cody, Buffalo Bill’s Town in the Rockies. Her book Images of America: Cody, was published in 2008, and Then and Now: Cody, in April 2011.

Post 248

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.