What is an herbarium and why do they matter?

By Amy Phillips, Curatorial Assistant

Draper Natural History Museum

The Draper Natural History Museum maintains two herbarium collections. One is a sister collection to the Rocky Mountain Herbarium at the University of Wyoming. A “sister collection” means that the collector took several specimens from the field, and they were separated into different collections. The second herbarium collection is the personal herbarium collection of Erwin F. Evert. These two collections provide important information about the biodiversity of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

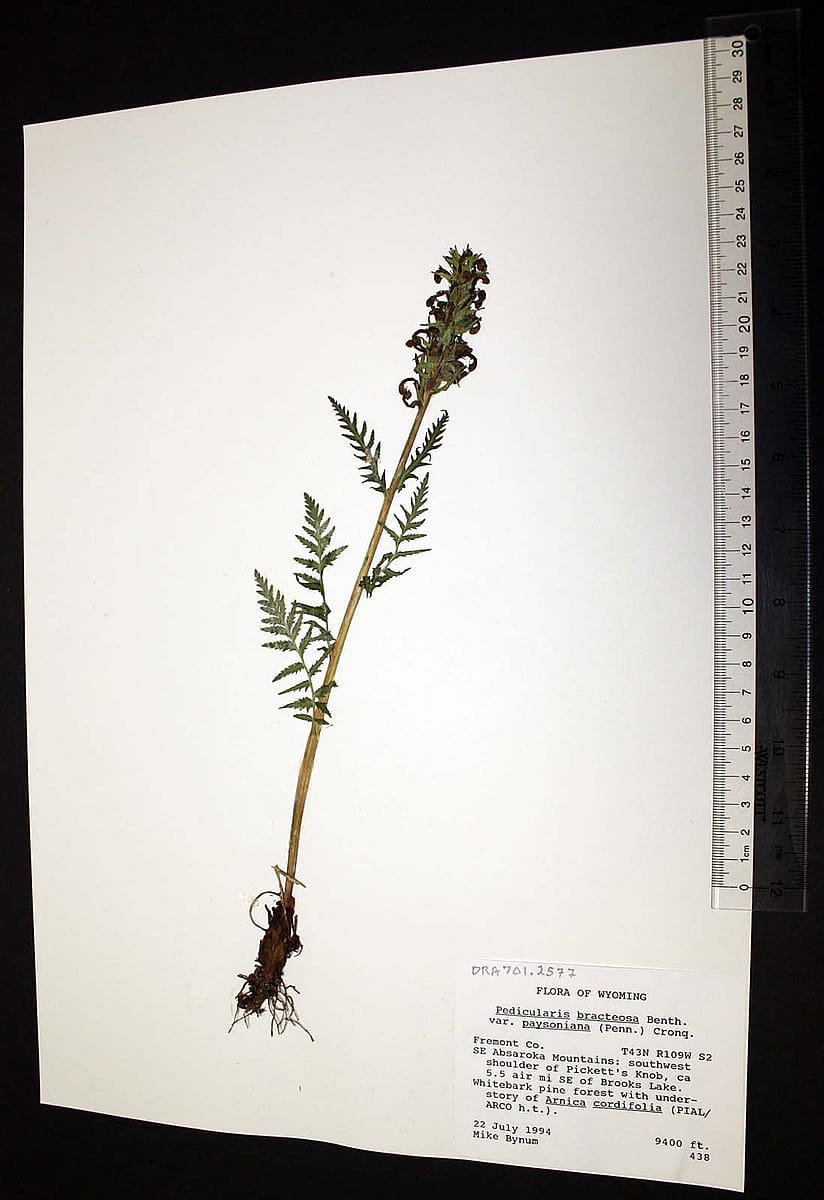

An herbarium (plural herbaria) is a collection of dried plant specimens that is useful for both research and education. Each specimen in the collection has a label stating who collected the plant, geographic and habitat information, and when it was collected.

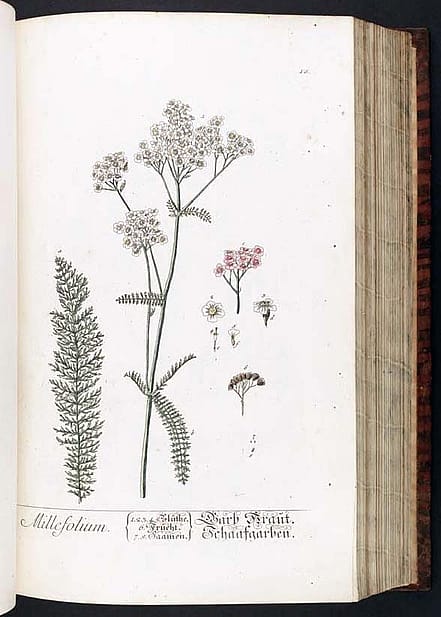

Herbaria date back to the 16th century when Luca Ghini was a professor of medicine and botany at the University of Pisa in Italy. Ghini’s introduced mounting plants on paper and binding them into volumes that could be used for teaching and research. Herbaria during this time were the work of physicians who relied heavily on botanical knowledge for treating ailments.

At this same time, colonization brought naturalists to entirely new ecosystems. To document the new plants from these places, plant specimens were dried and mounted. The mounted plants were bound into booklets and then often artists were hired to create illustrations that could be more widely distributed.

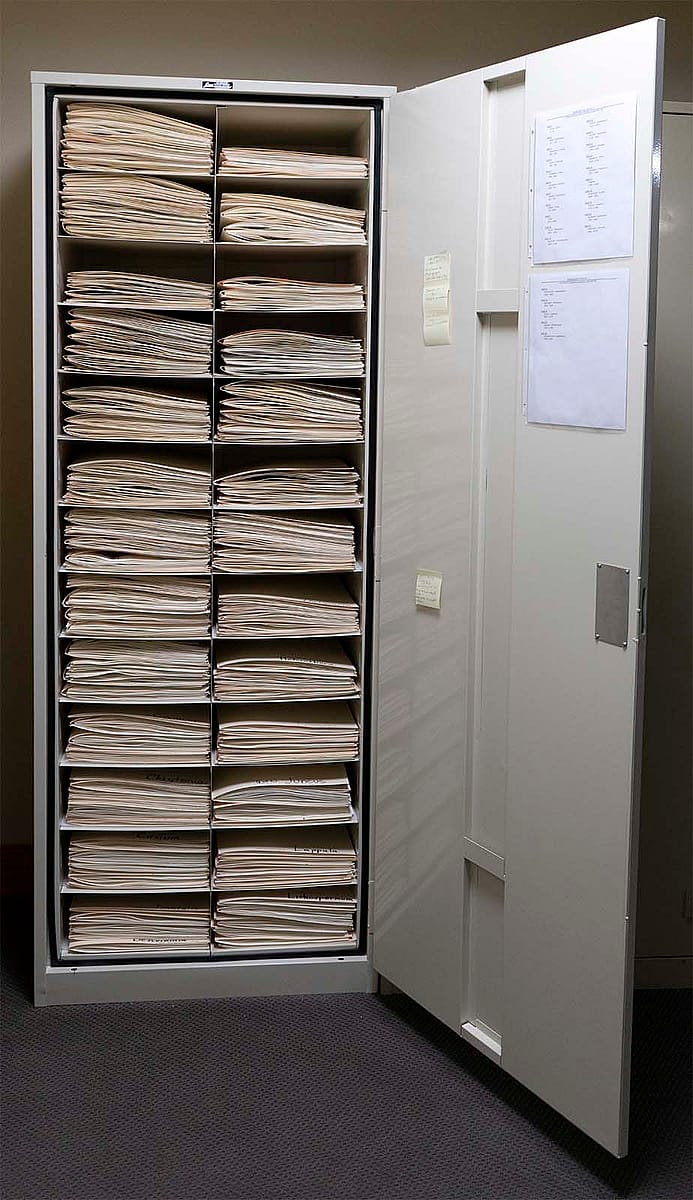

In 1751, Carolus Linnaeus made a slight change to the traditional herbarium. Linnaeus advised mounting a single specimen per sheet of paper and, instead of being bound, the specimens stored in cabinets with special, narrow shelves. This new system allowed new specimens to be integrated into the collection gradually over time.

From Ghini to Linnaeus and beyond, plants became “known to science” through the process of inclusion in an herbarium. This just meant the plant and its habitat were described. After Linnaeus introduced taxonomy, a seven-level hierarchy for classifying organisms, botanists were responsible for fitting plants into that hierarchy. This common language allowed botanists to talk about plants throughout the world and their relatedness. However, in many cases, this Western science language dismissed traditional ecological knowledge about the plants that had been known to indigenous communities for centuries.

Today, herbaria fulfill many of the same roles as they did early on in their history while taking on new meanings. Herbaria continue to provide a record of biodiversity and help botanists classify plants. With recent advances in technology, herbaria provide a treasure trove of genetic information. Researchers can source DNA from specimens to learn about plant evolution, populations, and even biodiversity loss.

The record of biodiversity of native plants is increasingly important under the spread and threat of invasive species. For example, one of the most familiar invasive plants in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is cheatgrass or downy brome. Cheatgrass has a shallow root system allowing it to spread quickly and take over vast areas of land. Not only does cheatgrass cause more intense fires than are historically normal for the area, but it also poses a threat to native ungulates that rely on nutritious grasses late into the fall. Cheatgrass completes its reproductive cycle early in the summer, increasing its susceptibility to fires while taking the place of more nutritious, late-season grasses relied on by pronghorn, mule deer, elk, and more.

Curation of natural history collections like the Rocky Mountain Herbarium and Erwin F. Evert Herbarium require care and a keen attention to detail. Meticulously collected specimens, such as those found in these two collections provide essential details that allow researchers to track changes in individual species and in some cases, ecosystems over time. Often, museum collections are the primary reference materials that scientists use to understand relationships between species and inform our understanding of different processes such as evolution. Museum collections also contain holotypes or the original specimen upon which a species is first described to the scientific community. When an unknown species is encountered in the wild, photos or specimens are compared to museum collections to determine whether it is a known organism, a variant, or a new species entirely. Stay tuned for a blog post on the holotypes found in the Erwin F. Evert collection!

Sources

What is a herbarium? Duke University: https://herbarium.duke.edu/about/what-is-a-herbarium

What is an herbarium? Brown University: https://www.brown.edu/research/projects/herbarium/about/what-herbarium

What is a herbarium? Florida Museum: https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/science/what-is-a-herbarium

Written By

Amy Phillips

Amy Phillips brings seven years of experience in the cultural heritage field to her position as Curatorial Assistant at the Center of the West's Draper Natural History Museum. She is the co-Principal Investigator on the “Bison of the Bighorn Basin” Project, which employs faunal analysis to learn about past bison ecology in the geographic Bighorn Basin using more than 100 bison crania sourced by community engagement. Amy also serves on the Society of American Archaeology Public Outreach Committee and as an appointed member of the Park County Historic Preservation Commission. She has research interests in the relationship between humans and their environments in the past and present, taphonomy, and bison ecology. Amy is currently pursuing her Master of Science in Cultural Resource Management, Archaeology from St. Cloud State University.