How trees survive winter

When trees first evolved, they existed only in the tropics and for good reason—50 percent of the tree is water. Cold temperatures turn water into ice, causing it to expand. This means that freezing temperatures could cause the water in a tree’s cells to turn to ice, possibly bursting the cells! So how do trees seemingly defy laws of nature to survive during the winter? Adaptation!

Bark provides protection for trees against many things including insects and fire. It also acts as insulation, protecting them from the worst of the cold. Beneath their bark, the tree has more tricks to stay alive through winter.

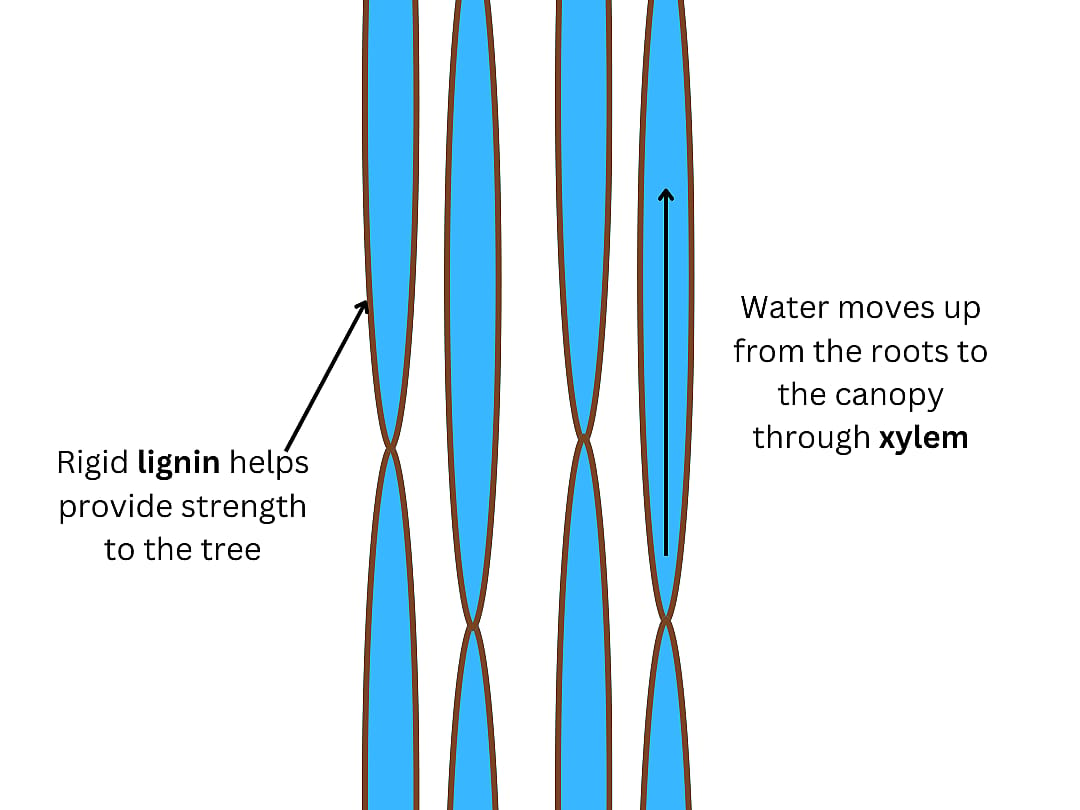

A tree distributes water from its roots to its leaves through the xylem. The xylem is made of dead, water-conducting cells known as tracheary elements that have modified cell walls that allow water to pass from cell to cell from the roots to the canopy. When the water freezes, you can think of these dissolved minerals becoming gaseous bubbles separated from the water. When temperatures warm and the water turns back into a liquid, the minerals do not become dissolved into the water again. The cell walls prevent these undissolved minerals to pass through, but if there are too many of them it can prevent the water from traveling upwards, against gravity, to the canopy of the tree, effectively cutting off water from the tree.

Trees can handle the water in the xylem freezing, it is those gaseous bubbles that can cause trouble. So, trees in cold climates have narrow xylem running from the roots to the canopy. Narrow channels mean that the gaseous bubbles cannot become too large or numerous, allowing the water to continue to travel upwards, even if there are some small bubbles in the water.

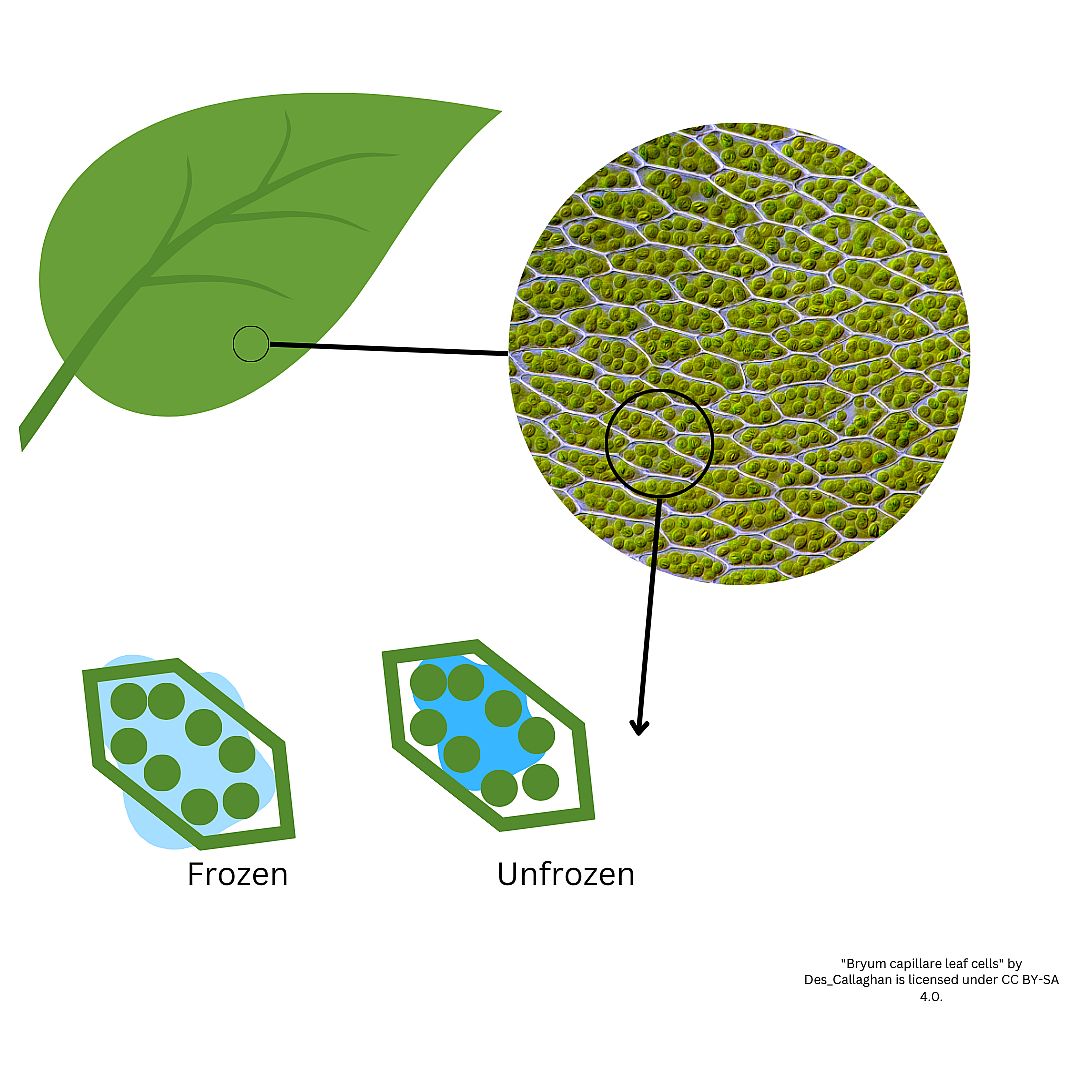

But trees can’t allow the water in their living cells to freeze because then their cells would burst. Think of a spring snowstorm that hits after deciduous trees have put their leaves back on. After the snowstorm, the leaves look wilted. This is because the water in their leaves froze and burst the cell walls.

As a preventative measure to keep this from happening, deciduous trees drop their leaves when they experience cold temperatures and shorter daylight. As living cells, leaves would require a constant water supply through the winter, but their large surface areas, perfect for capturing sunlight and carbon, would become liabilities susceptible to freezing. The dropped leaves of the deciduous tree provide an important layer of insulation on the ground, keeping the tree and other organisms safe from the worst temperatures during the cold months and recycling nutrients into the soil.

However, coniferous (or evergreen) trees keep their leaves during the winter. The needles of a coniferous tree have less surface area than broad leaves of a deciduous tree and are less of a liability. Both deciduous and coniferous (or evergreen) trees protect themselves from the cold by producing their own version of anti-freeze. When the water between cells freezes, the water within the cells becomes thick and sugary. This thick, sugary sap can keep moving from cell to cell through the xylem even if it moves slowly. Sound familiar? Some trees, such as the maple tree, have sap that can be tapped for syrup. Coniferous trees produce an extra-concentrated version of this anti-freeze. This combined with the needle-like form of their leaves allows them to keep their needles through the winter.

Written By

Amy Phillips

Amy Phillips brings seven years of experience in the cultural heritage field to her position as Curatorial Assistant at the Center of the West's Draper Natural History Museum. She is the co-Principal Investigator on the “Bison of the Bighorn Basin” Project, which employs faunal analysis to learn about past bison ecology in the geographic Bighorn Basin using more than 100 bison crania sourced by community engagement. Amy also serves on the Society of American Archaeology Public Outreach Committee and as an appointed member of the Park County Historic Preservation Commission. She has research interests in the relationship between humans and their environments in the past and present, taphonomy, and bison ecology. Amy is currently pursuing her Master of Science in Cultural Resource Management, Archaeology from St. Cloud State University.