The Herbarium of Erwin Evert

An herbarium is a collection of dried plant specimens useful for both research and education. Each specimen in the collection has a label stating who collected the plant, where it was growing, and when it was collected. The Draper Natural History Museum (the Draper) curates two herbarium collections. One is a sister collection to the Rocky Mountain Herbarium at the University of Wyoming. The second herbarium collection is the personal herbarium collection of Erwin Evert. The Draper was gifted the Erwin Evert collection in 2018. This collection represents the life work of Erwin Evert. His 2010 book, Vascular Plants of the Greater Yellowstone Area: An Annotated Catalog and Atlas (Figure 1), is also based on the specimens within the collection.

Kent Houston, former Soil Scientist and Ecologist with the Shoshone National Forest remembers, “I remember Erwin walking in the front door of the Center of the West in the Spring of 2010. He held a copy of his self-published book, Vascular Plants of the Greater Yellowstone Area: An Annotated Catalog and Atlas. He had a big smile and was quite proud. The book was the result of over 40 years of botanizing and collecting in the Greater Yellowstone. It was the first publication which thoroughly covered the flora of the Greater Yellowstone backed by voucher specimens.”

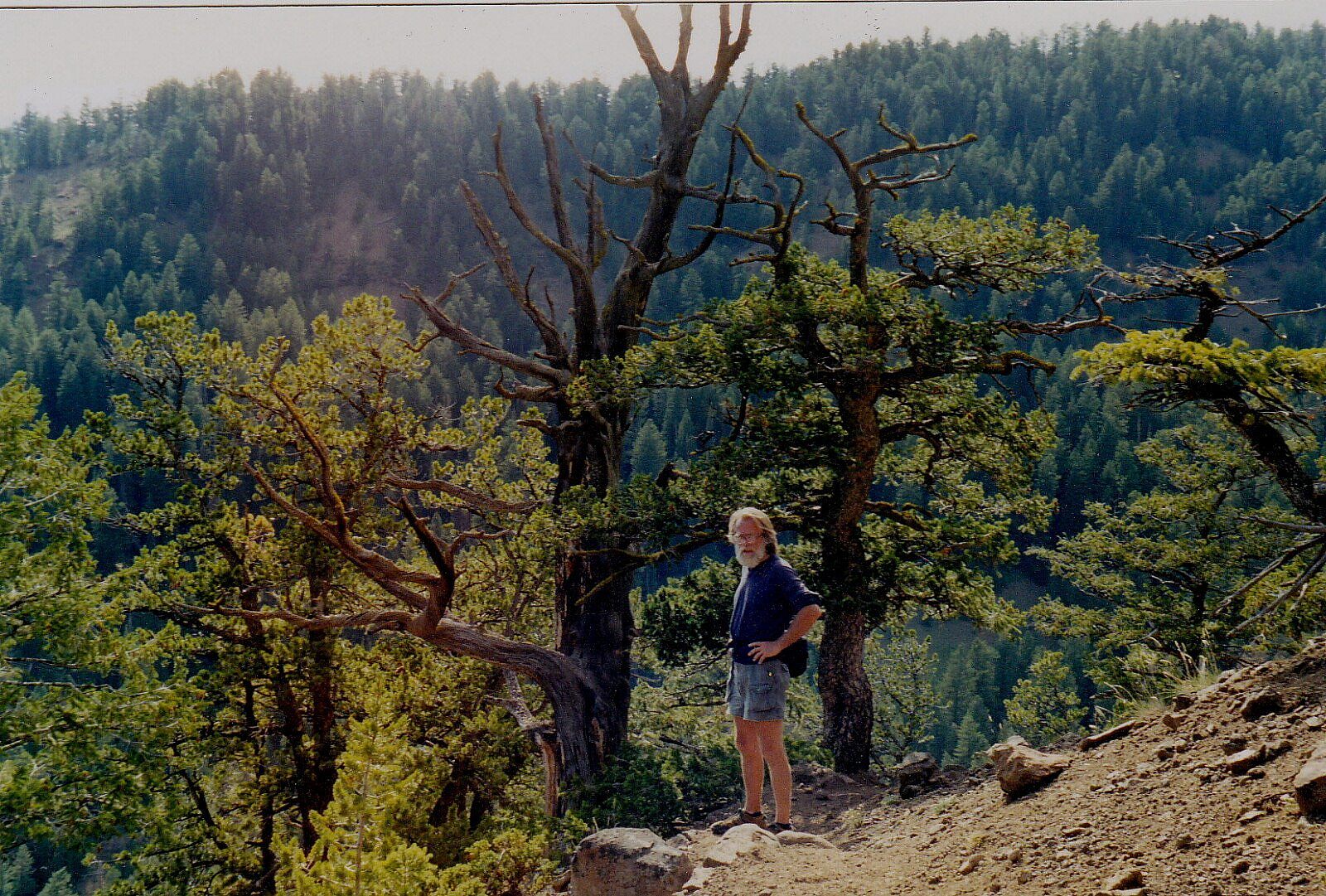

Evert (Figure 2) was born in Chicago in 1940. He received a Bachelor of Science from Roosevelt University in zoology and chemistry before teaching high school biology and zoology. Although he had a background in zoology, Evert was a self-taught botanist.

In the 1960s, Evert made a trip to Yellowstone National Park and fell in love with the area. Roughly a decade later, Evert and his wife purchased a cabin on the North Fork of the Shoshone in the Kitty Creek drainage. The cabin would serve as Evert’s base for exploring the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE) and its rich plant diversity.

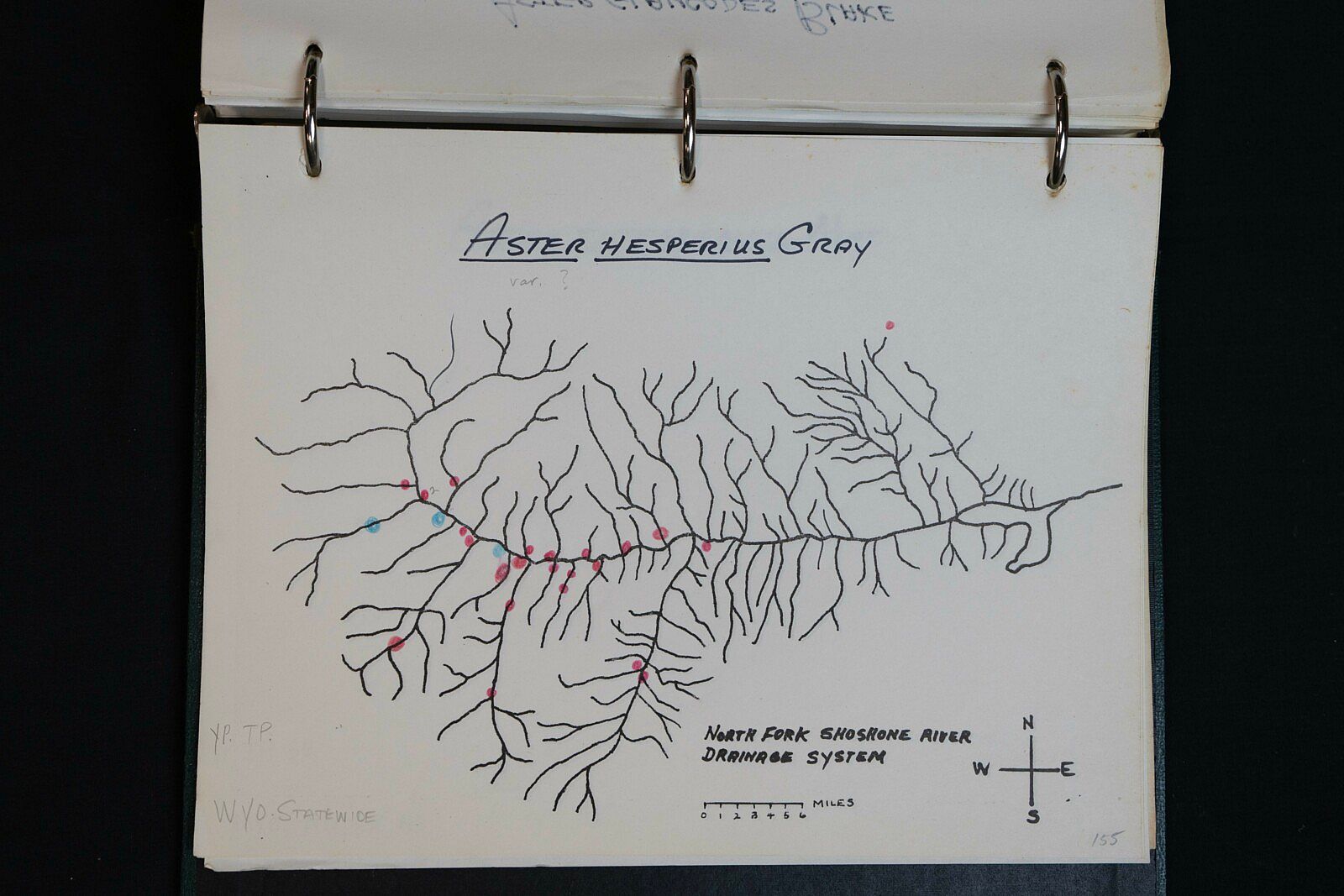

From the cabin on Kitty Creek, Evert would explore drainages, mapping plants on hand-traced maps (Figure 3). Once collected, plants were carefully pressed in newspaper before being mounted on large sheets of paper and given a unique number. While Evert maintained a personal collection, now housed at the Draper Natural History Museum, specimens collected by Evert were also shared with organizations such as the Morton Arboretum, Rocky Mountain Herbarium, New York Botanical Gardens, and the University and Jepson Herbarium at the University of California, Berkeley. He was a charter member of the Wyoming Native Plant Society, formed in 1981. In 1986, he received the honor of having a plant named after him when Ron Hartman and Rob Kirkpatrick named the Evert Desert Parsley or Evert’s waferparsnip, Cympoterus evertii (Figure 4).

Evert was personally responsible for naming four previously undescribed species from the GYE including Aromatic pussytoes (Antennaria aromatica), Absaroka biscuitroot (Lomatium attenuatum), Absaroka beardtongue (Penstemon absarokensis), and Shoshonea (Shoshonea pulvinate). Each species has a “holotype,” one specimen from which the species is described, and “isotypes,” duplicates of the holotype. Evert sent the holotypes for all the above species to the Rocky Mountain Herbarium while sharing isotypes with other facilities. It was important for the holotype to be part of a public institution where researchers could access it. In many cases, Evert reserved the first specimen he discovered for his personal collection.

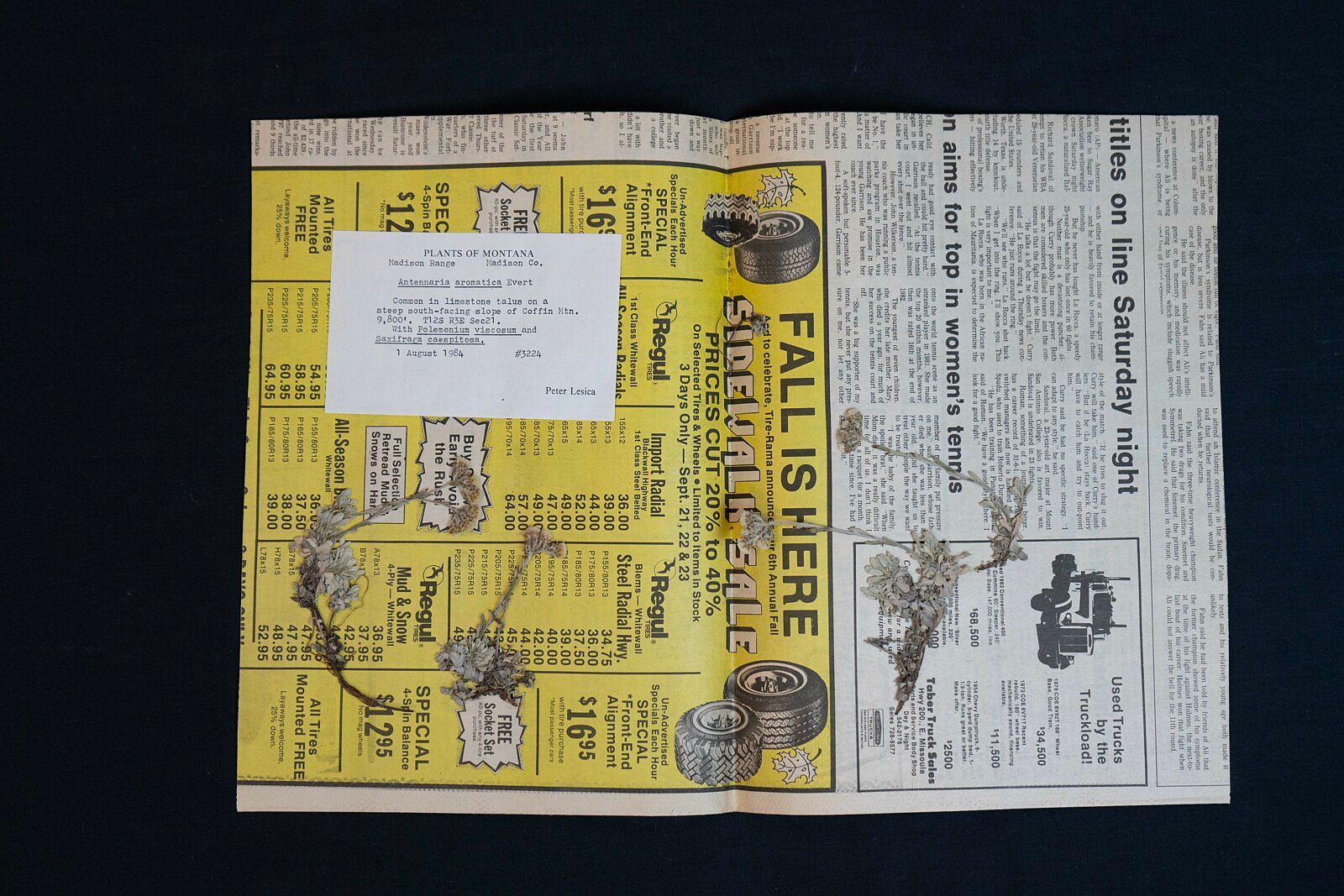

Aromatic pussytoes (Antennaria aromatica), seen in Figure 5, was formally described by Evert as a new species in 1984. Pussytoes are thought to get their name for their flowers which resemble tiny cat’s feet. Because Antennaria are an incredibly diverse group, Evert understandably began his introduction of yet another species hesitantly: “Because over three hundred North American species of Antennaria are listed in the Gray Herbarium Card Index, it is with some trepidation that I describe yet another one” (Evert 1984). Evert discovered the holotype for the species in the Beartooth Range along highway 212 in 1981 but collected specimens as early as 1980.

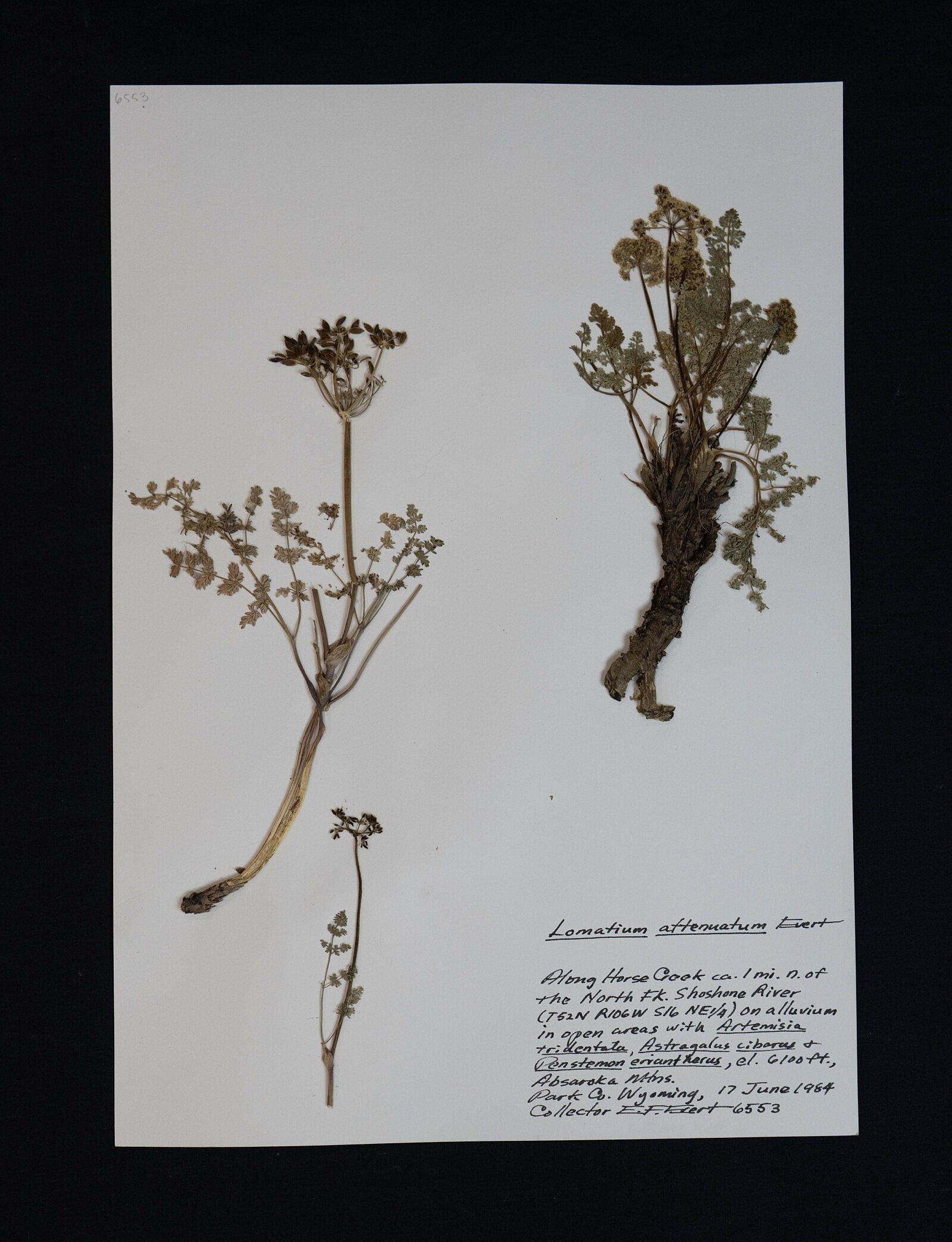

Absaroka Biscuitroot (Lomatium attenuatum) was formally described by Evert in 1983, but first found in 1975. The specimen in the Draper’s collection comes from the year after he formally named and described the species, found along Horse Creek (Figure 6).

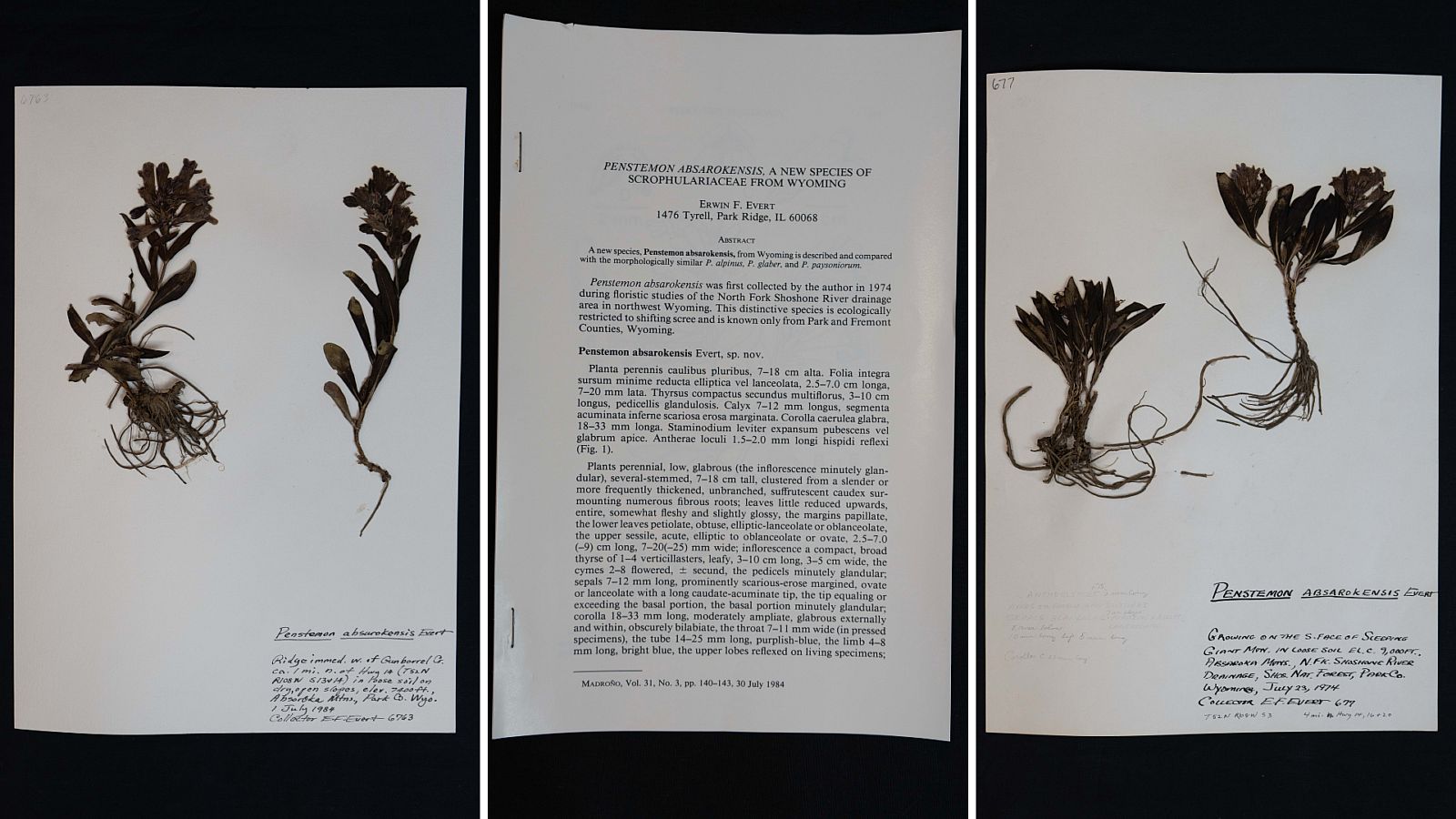

Penstemon absarokensis was discovered by Evert on Sleeping Giant Mountain in 1974 (far right of Figure 7). Ten years later, he published a paper in Madroño, a journal published by the California Botanical Society, describing the plant as a new species. The plant is described down to the smallest detail, complete with measurements. The Draper has three mounts of this flower including the specimen collected in 1974 during Evert’s initial discovery.

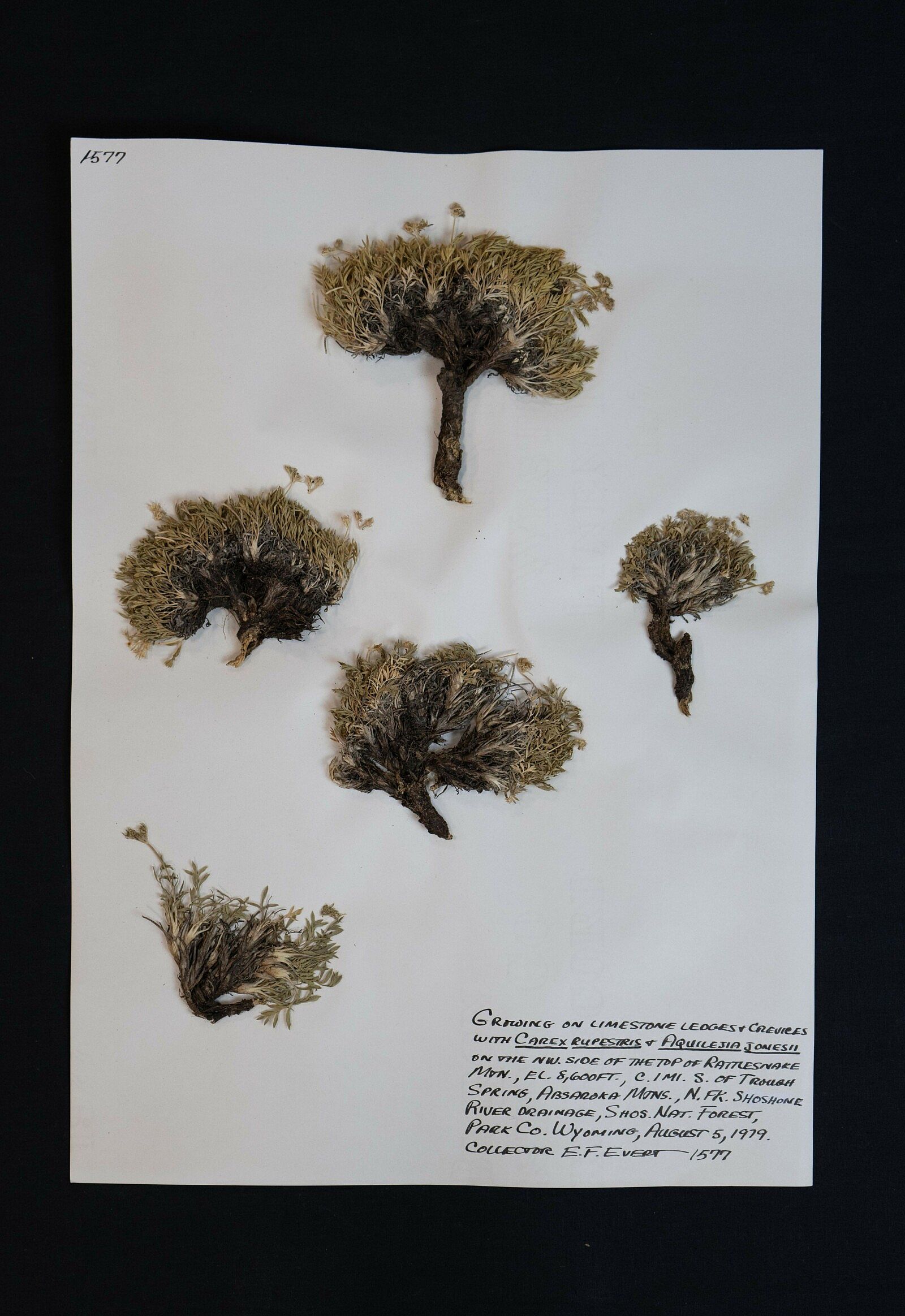

Shoshonea pulvinata, my personal favorite of Evert’s discoveries, was described by Evert and Lincoln Constance in Systematic Biology in 1982. Constance was the “patriarch of botany” at the University of California, Berkeley (Mishler, Baldwin, Park, n.d.). Evert found Shoshonea pulvinata, or the Shoshone carrot, growing on rocky cliffs on Rattlesnake Mountain (Figure 8). Together Evert and Lincoln described the species from the specimen now housed at the Rocky Mountain Herbarium, but Evert once again kept the earliest specimen found in his personal collection. Thanks to Evert’s efforts, we now know that Shoshonea pulvinata is endemic to the Absaroka, Pryor, and Owl Creek Mountains. It is a low-growing plant that produces beautiful yellow flowers (Figure 9).

Evert had a fatal encounter with a grizzly bear in 2010. Through his passion for plants, Evert not only explored the botanical wonders of the Absaroka and Beartooth Mountains, but also formally described four new species, received the honor of having one species named after him, and discovered the first occurrence in Wyoming of many known species.

Written By

Amy Phillips

Amy Phillips brings seven years of experience in the cultural heritage field to her position as Curatorial Assistant at the Center of the West's Draper Natural History Museum. She is the co-Principal Investigator on the “Bison of the Bighorn Basin” Project, which employs faunal analysis to learn about past bison ecology in the geographic Bighorn Basin using more than 100 bison crania sourced by community engagement. Amy also serves on the Society of American Archaeology Public Outreach Committee and as an appointed member of the Park County Historic Preservation Commission. She has research interests in the relationship between humans and their environments in the past and present, taphonomy, and bison ecology. Amy is currently pursuing her Master of Science in Cultural Resource Management, Archaeology from St. Cloud State University.