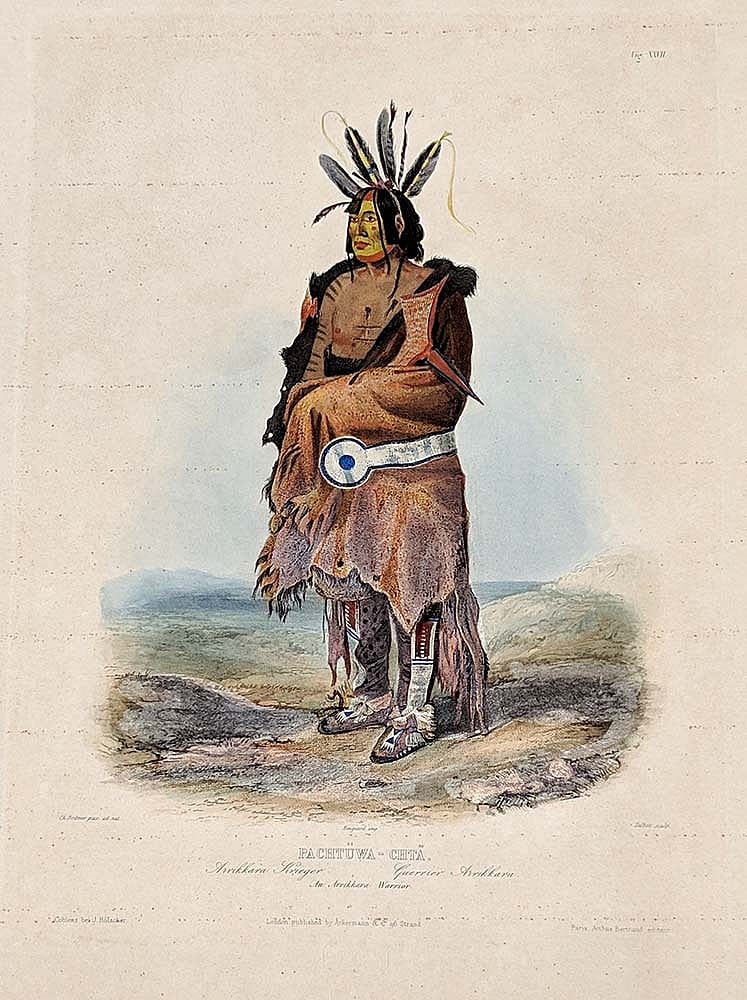

Paul Dyck Collection: Arikara

The Arikara

The Arikaras, who call themselves Sahnish, migrated from present-day eastern Texas and nearby parts of Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Louisiana to the central Plains (ca. 1400), primarily now Nebraska. This is where their earth lodge development and agricultural knowledge of corn developed. Later they moved further north to build villages on the Grand and Cannonball Rivers in what is now northern South Dakota. In the 1700s, the Arikaras controlled land along the Missouri river for one hundred miles.

Arikaras are closely related to the Skiri Pawnees; they split when both groups were settled on the Loup River in Nebraska. Both groups share linguistic characteristics of the Caddoan language family—but the Pawnee and Arikara languages are not mutually understandable.

The Arikara were farmers, raising corn, beans, tobacco, and squash both for food and to trade with other tribes in the area. Like the Hidatsa, the women worked and owned the gardens. Corn or maize was such an important staple of Arikara society that is was referred to as “Mother Corn.” They also had seasonal buffalo hunts, tracking the herds while utilizing easily portable tipis. Their agricultural success also balanced the power with the non-farming Lakota, aggressive neighbors who traded for the commodities the Arikara produced.

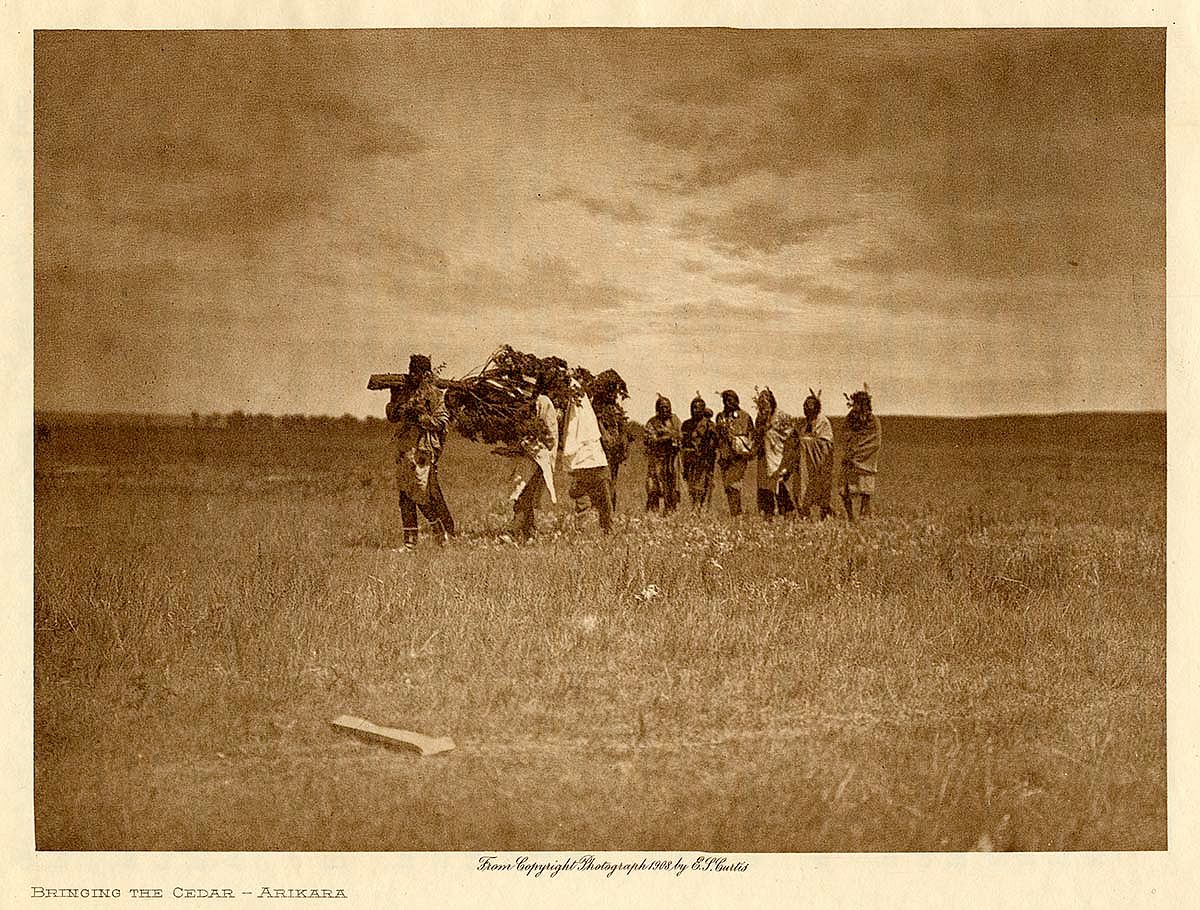

The Mother Corn Ceremony was a ritual that centered on the theme of world renewal, and linked the universe through Mother Corn (represented by a cedar tree) to the keepers of sacred bundles and their kin. In everyday life, Mother Corn instructed the people in the right ways of living in the world.

By the time of the Corps of Discovery in 1803, smallpox epidemics, that had also affected the Mandan and Hidatsa, reduced the Arikara population to approximately 2,000 living in three smaller villages in 60 earth lodges on an island in the Grand River. The Corps stayed at the Arikara villages for five days, discussing trade issues and the possibilities of Arikara peace with the Mandan and Hidatsa. The Arikara agreed to consider peace with the tribes to the north.

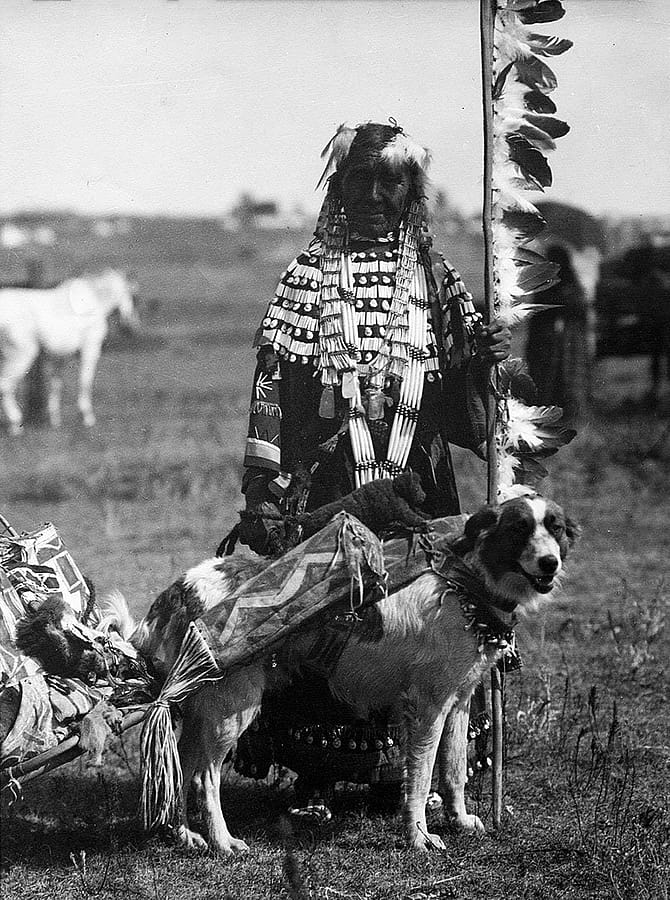

Traditionally an Arikara family owned 30–40 dogs. The people used them for hunting and as sentries, but most importantly for transportation, before Plains tribes adopted the horse. Many of the Plains tribes had shared the use of the travois, a transportation device to be pulled by dogs. It consisted of two long poles attached by a harness at the dog’s shoulders, with the butt ends dragging behind the animal; midway, a ladder-like frame of hide strips was stretched between the poles; it held loads that might exceed 60 pounds. Women used dog-pulled travois to haul firewood or infants. These were also used for meat transport during the seasonal hunts; a single dog could pull a quarter of a buffalo. The introduction of the horse in the mid-18th century changed everything, from transportation to hunting and warfare.

The Arikara War took place in August 1823 between the United States and the Arikara Nation near the Missouri River in present-day South Dakota. Arikara warriors had previously attacked General Ashley’s fur trading expedition traveling to the Yellowstone River to establish trade. The U.S. responded with 230 soldiers, 750 Sioux warriors and 50 of Ashley’s trappers, all under the command of Col. Henry Leavenworth. This conflict was the first United States military conflict with Western Native people, and set the tone for future American encounters between the Crow and Blackfeet further to the west.

In June 1833, the American artist George Catlin passed the Sahnish villages at the Grand River, but did not go ashore because he considered them “hostile.” That same year, the Arikara left the banks of the Missouri River after two successive crop failures and conflicts with the Mandan. They rejoined the Pawnees for three winters at the Loup River. However, this location made them susceptible to attack by Euro-Americans and the Lakota, causing a move back to Missouri River region.

In June 1837, an American Fur Company steamboat travelled westward up the Missouri River from St. Louis. Its passengers and traders aboard infected the Arikara, Mandan, and Hidatsa tribes with the third smallpox outbreak in the region. The tribe was decimated. In 1856, a fourth smallpox outbreak occurred in the Star Village at Beaver Creek (across from Fort Berthold). This last outbreak, and the constant raids by the Lakota forced the move of some Arikara to Like-a-Fishhook village near Fort Berthold, but some did remain at Star Village.

In 1862, the Arikara joined the Hidatsa and Mandan at Like-a-Fishhook Village in what is now North Dakota. For work, many Arikara and Crow men scouted for the U.S. Army at nearby Fort Stevenson against their traditional enemies the Sioux. In 1874, the Arikara guided the Army on the Black Hills Expedition. The Arikara Scouts were also present at the 1876 Little Big Horn Expedition with Geo. A. Custer.

Today the Arikara, Hidatsa, and Mandan—the Three Affiliated Tribes—share the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota.