Paul Dyck Collection Hidatsa

The Hidatsa

The Hidatsa (referred to as the Minnetaree by their allies, the Mandan and Assiniboine) call themselves Hiraacá—traditionally thought to mean “willow.” Having originally lived in the Miniwakan or Devil’s Lake region in what is now eastern North Dakota, by the early 1600s, the Hidatsa had moved to settle along the Missouri River in what is now west-central North Dakota—near the Mandan. The two tribes were usually on good terms, both speaking Siouan dialects, although the languages were not mutually intelligible. The Hidatsa lived near the junction of the Knife and Missouri Rivers, about sixty miles up from the Mandan.

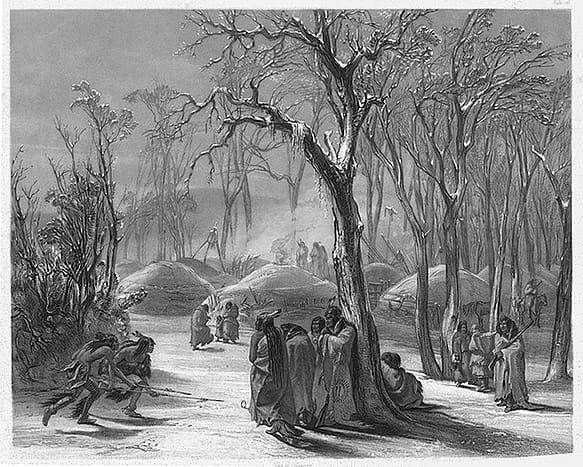

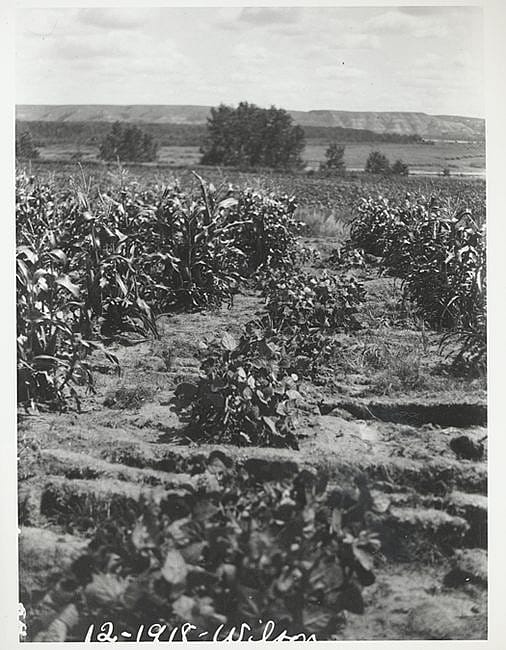

The Hidatsa lived in substantial earth-covered lodges clustered in villages of several hundred to more than a thousand individuals. These stable communities were perched on the rims of terraces overlooking the Missouri River floodplains. In the lowlands, the Hidatsa grew bountiful gardens of corn, beans, squash, and sunflowers all owned and tended to by the women, while the men hunted white tailed deer and other woodland animals. Behind the villages were the river bluffs that separated the valley from the rolling, upland plains, where they hunted pronghorn and the massive herds of buffalo. The products produced denoted the Hidatsa villages as major part of the ancient indigenous trading center of the Plains—and also later when the Euro-Americans arrived.

Hidatsa society is matrilineal—meaning descent is traced from the mother’s side of the family. Hidatsa say that a person comes into the world through their mother’s clan, and leaves through their father’s clan. Meaning that the mother’s clan bestows membership and belonging; while the father’s clan gives them distinct rights and responsibilities. The clan structure arranged an individual’s participation in life events and ceremonies.

After a smallpox epidemic in 1781, the Mandan moved upriver to live near the Hidatsa, as their numbers had been so reduced they were no longer able to defend their villages. Farther downriver, near the mouth of the Grand River, lived the Arikara, the third group of village dwelling Natives. Although they spoke a different language (being related to the Pawnee of Nebraska), their villages and way of life were much the same as those of the Hidatsa and Mandan.

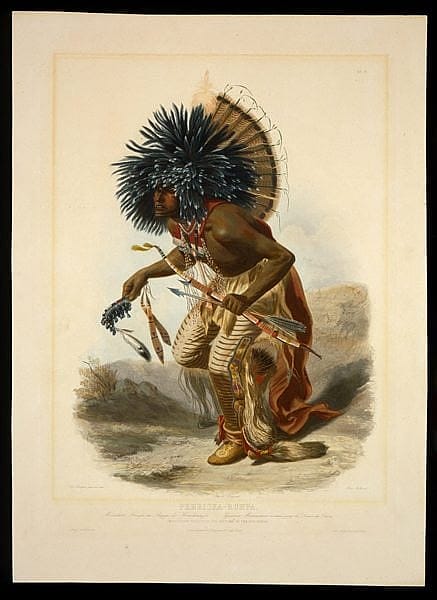

By 1804, when the Lewis and Clark and the Corps of Discovery visited Upper Missouri villages, the Hidatsa were in three distinct groups: the Awatixas, the Awaxamis, and the Hidatsa proper; the Hidatsa proper living in the largest village on the Knife River. The American artist George Catlin visited the tribes in 1832, and remained with them for several months in 1832. In 1833 – 1834, the Swiss artist Karl Bodmer, travelling with German explorer Prince Maximilian zu Wied-Neuwied, drew and painted the clothing and people and cultures of the villages.

In one of Bodmer’s most stunning portraits, Pehriska-Ruhpa wears ceremonial regalia made to sway with the drum and rattle of the dance. The elaborate feather bonnet was made from magpie tail feathers and a wild turkey tail. Dyed horsehair floats from sticks attached to the shafts of the turkey feathers towards the rear.

Both Catlin and Bodmer’s artworks recorded the Hidatsa and Mandan societies, that where were rapidly changing under pressure from encroaching settlers, infectious disease, and government restraints.

After an 1834 attack by the Dakota and the 1837 smallpox epidemic that reduced the Hidatsa to about 500 people, the three groups merged with the Mandan at Like-a-Fishhook Village in 1845. The Arikaras joined them in 1856.

Like their allies the Mandan and Arikara, the Hidatsa had many losses of their hereditary land area. However, the Army Corps of Engineer’s construction of the Garrison Dam in 1951 had an extraordinarily severe impact on the tribes, having been compared as to being equal in its severity as the 1837 smallpox epidemic that nearly reduced the Hidatsa to cultural extinction. It not only flooded and destroyed the fertile bottomlands they farmed, it also fractured the communities, separating them across wide distances. Once nearby neighbors, they were now surrounded by immense lakes cutting them off from one another. Some of this story is told in the movie in the earth lodge in the Plains Indian Museum.

Today, Hidatsa have their distinct community segments on the Fort Berthold Reservation—the communities at Shell Creek and Mandaree. The Hidatsa at Fort Berthold are emphasizing the need to retain native speakers of their language through projects like the Hidatsa Language Program at Mandaree, and through their website.