Director’s Preface, Second Edition

In 1996, the Buffalo Center of the West (then the Buffalo Bill Historical Center), with the financial support of William B. Ruger and the Nelda C. and H. J. Lutcher Stark Foundation, published a two volume edition of Frederic Remington: A Catalogue Raisonné. It contained four essays by the catalogue’s organizers, Peter H. Hassrick and Melissa J. Webster, the artist’s timeline, bibliography, full exhibition history and an accompanying CD rom containing additional catalogue information on each work.

The 1996 edition contained entries with black and white illustrations for over 3,000 flat works (paintings, watercolors and drawings), with about 100 of those replicated as color plates. Of the 3,000 works, about one third were known at that time as originals, while the remaining two thirds were known only as they had been illustrated in public literature during Remington’s lifetime.

The first printing in an edition of 3,000 copies is sold out at this time, and more than 200 new original works have been identified since 1996. Several hundred others have changed hands in the interim as well. As a consequence, the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, in concert with the Frederic Remington Art Museum, Ogdensburg, New York and the Stark Museum of Art, Orange, Texas have enthusiastically collaborated to reprint and update the catalogue raisonné. This current printing contains six new essays, two by Hassrick (now the museum’s Director Emeritus and Senior Scholar) and Webster (now Speidel) along with four by new scholars in the field; Dr. Sarah Boehme (Stark Museum of Art), Dr. Doyle Buhler (recent graduate of the University of Iowa), B. Byron Price (University of Oklahoma) and Laura Fry (Tacoma Art Museum). It will be patterned after the volume Charles M. Russell: A Catalogue Raisonné published in 2007 by the University of Oklahoma Press. This new Remington book, as did the first edition, concentrates on Remington’s flatwork. It contains over 100 color plates and features a special accompanying web component that will contain more than 3,400 works, with approximately 1,000 in color along with full, updated curatorial information including title, date, medium, size, inscriptions, provenance, exhibition and publication history and commentary (when information or insights were available). The website allows the museum to stay current with new discoveries and will be systematically updated by museum staff. It also reprints all the essays, timeline, and bibliography contained in the initial volumes. The combination of printed catalogue and website will result in a body of knowledge that provides ample credit to the artistic genius of Remington and a formidable research tool into his life and art for scholars, collectors and a full range of students and aficionados of American and western art.

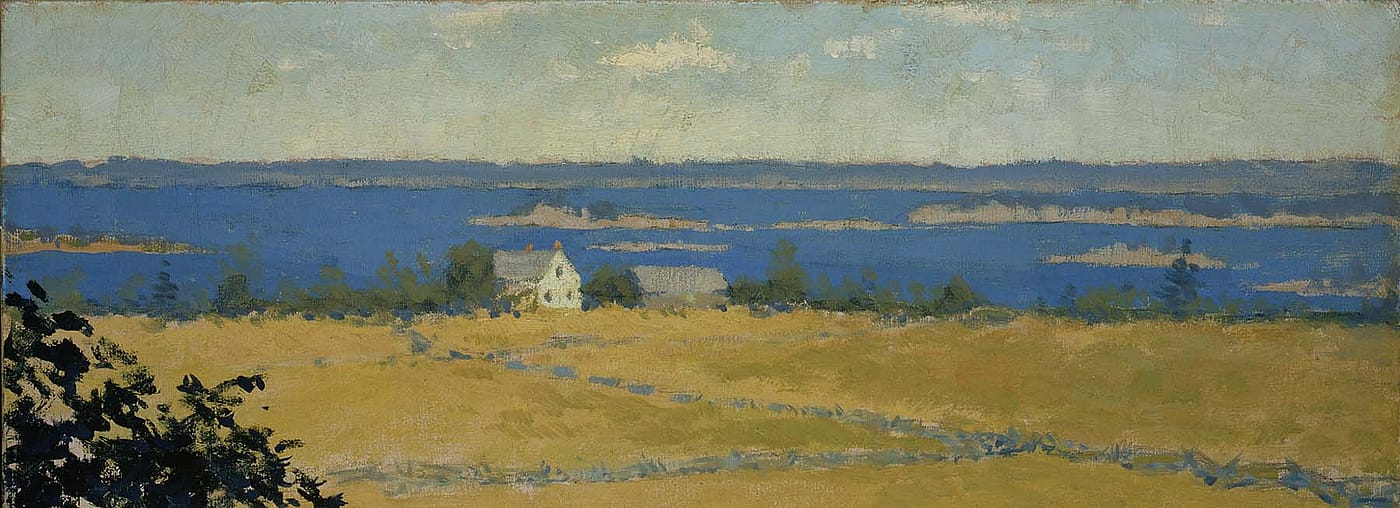

Since the first edition of the Remington catalogue raisonné was published, there has been a welcome advancement in Remington scholarship. The National Gallery of Art hosted an exhibition, Frederic Remington: The Color of Night in 2003 that revealed the contributions Remington made as an Impressionist painter. Two other museums, the Frederic Remington Art Museum in 2000 and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston the same year published in-depth surveys of their Remington collections. Remington scholarship by these collegial institutions, not to mention published works by several independent scholars in recent years, has been substantially advanced. Yet, Remington is a larger than life presence in American art. The printed volume and this companion website provide new voices and perspectives in studying this extraordinary figure.

The printed volume comprises seven chapters, each an independent entity but all connected in the effort to expand public knowledge of Remington and his art. Hassrick’s essay opens the discussion with an assessment of the authentication process that coincides with most of the catalogue raisonné entries. Remington is perhaps the most frequently faked of all American artists, so great care and judicious consideration must go into the determination of what objects to include in such a volume. Hassrick explains the different variations of inauthentic works and highlights how comparatively rare it is to actually find a new original work by the artist.

That essay is followed by a concise overview of Remington’s art and historical perspective by Ron Tyler that focuses on the artist as he developed from an illustrator in search of accurate detail to a fine art painter in search of truth. His understanding of what he called “men with the bark on” helped him focus on that pursuit. These men faced the ultimate test, and did so bravely. They guided the artist’s vision from a local or regional setting to embrace a universal verity. Remington and his art were defined by the ideal western figures he chose as his subjects. Though this limited him somewhat, it also proved quite timely and set Remington apart from most other American painters of his day. His was not simply a paean to his legendary “men with the bark on,” rough-hewn frontiersmen, but to the America’s common man in general. For that reason, in part at least, Remington rose to an ascendant position in the nation’s cultural history.

If Remington held a lofty position in matters of interpreting the American West for the public, he was bested by a master promoter of his day, William F. Cody. Laura Fry explores the structure and significance of the relationship between these two great agents of the West’s legacy. Memory and imagination informed the creative genius of both men’s work, and they have shared the pedestal as two of history’s best creators and commentators.

Remington spread the word about his West through written articles and through thousands of illustrations. It was illustrations that were his primary form of artistic communication. Another master artist of his day was the noted teacher and illustrator, Howard Pyle. Melissa Speidel opens the door to understanding what that method of visual communication meant for Americans in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Though Pyle’s subjects differed profoundly from Remington’s, their positions in the world of pictorial literature were essentially equal. Their relationship revealed the deep respect that these two titans of American illustration shared for one another, their mutual commitment to championing what they considered to be a unique, true American form of art and the extraordinary impact they had as an ensemble, not unlike Remington and Cody, on American artistic taste and historical perceptions.

Remington was born into an era of brutal human conflict with the Civil War and, conversely, into an era of emerging conservation ethos. Doyle Buhler discusses Remington’s sense of himself as a “heroic hunter.” He also addresses Remington’s association with Theodore Roosevelt and how the artist’s work was irrevocably tied to Roosevelt’s wildlife conservationist agenda. B. Byron Price treats another hugely significant animal issue related directly to Remington, that of the artist’s insuppressible bond with the horse. A topic that has been skirted over by generations of scholars now has become the definitive theme in Price’s thorough analysis of the artist and his equine idols.

The final essay presented in the printed catalogue is by Sarah Boehme. Her background as a student of the Taos artists has made her the ideal scholar to address the connection between Remington and the members of the famous Northern New Mexico art colony. Though too short-lived to fully embrace the Taos art aesthetic and perspective on Indian people, Remington was, late in life, an advocate for a beneficent vision of the West and a poetic pictorial interpretation of its Native people and themes.

The essays in the website’s accompanied printed volume weave a thread through the creative life of America’s most celebrated artist of the West. Together with the publication, this website represents a zenith in scholarship for western American art for which the Buffalo Bill Center of the West is duly proud.

Executive Director & CEO

Buffalo Bill Center of the West