James Bama

James Bama

1926 – 2022

By Thomas B. Smith

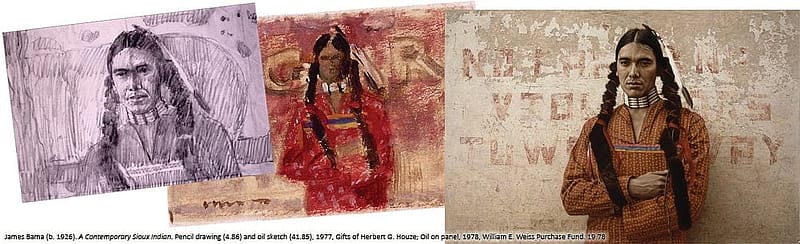

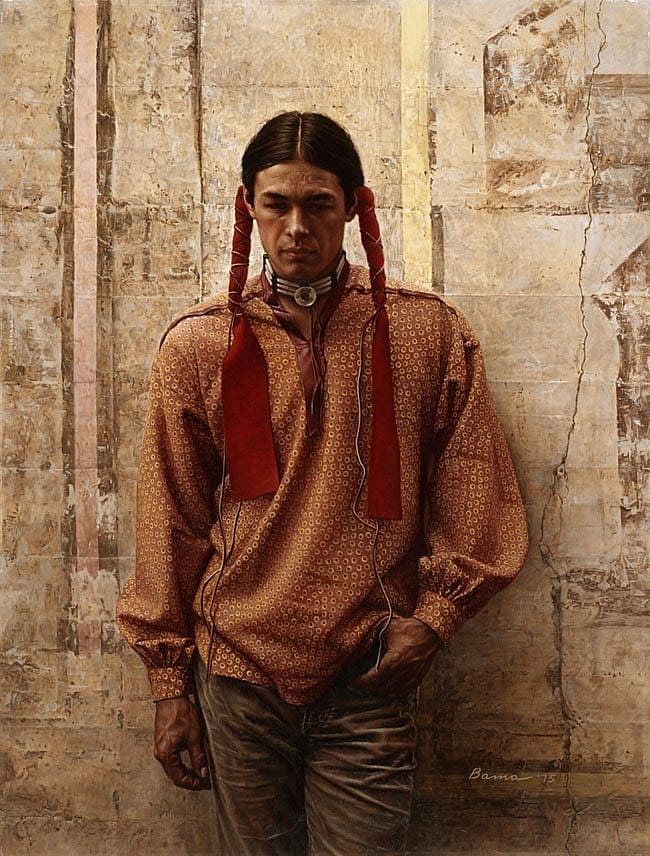

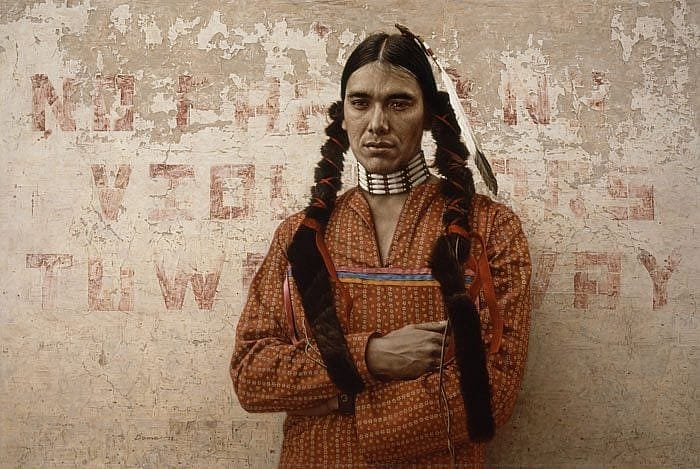

James Bama left a successful illustration career and his New York home for the solitude of the Absaroka Mountains of Wyoming and life as a Realist painter. Often overlooked in the scope of American art, Bama’s paintings hold their own when compared to other outstanding American Realists. Endowed with an intense work ethic and dedication to his art, he found all the subjects he needed in the people of the Yellowstone Valley. He discovered a West filled with rugged yet romantic modern day cowboys and Indians.

James Elliott Bama entered the world in 1926 amid the bustling atmosphere of New York City. Flash Gordon, Tarzan, and other comic strips with bold graphics stirred his imagination and planted the seeds of his desire to become a cartoonist.

Thanks to his emerging artistic talent, Bama was accepted into the prestigious High School of Music and Art. Upon graduation, he desired a career in illustration and developed the technical foundation he needed at the Art Students League in New York City. He enrolled in a class taught by well-known illustrator Frank Reilly, whose methods prepared students for a career in commercial art.

Under Reilly’s tutelage, Bama concentrated on the basics of art, including form, human anatomy, precise draftsmanship, and elements of composition, color, and depth. Reilly also introduced Bama to photography as a means of producing painting reference material.

Aiming high, Bama landed a job at the prestigious Cooper Studios in Manhattan. He quickly established himself as one of the firm’s leading illustrators, producing advertising images for such major clients as General Electric, Coca-Cola, and Ford, and popular magazines like Reader’s Digest and The Saturday Evening Post. In addition to his employment with the agency, Bama painted portraits for the Baseball and Football Halls of Fame and became the official artist for the New York Giants. He is also credited with original artwork for the television series Bonanza and Star Trek, and the poster for the 1967 film Cool Hand Luke. Perhaps Bama’s most memorable illustrative works were his covers for the 1960s Doc Savage series published by Bantam books.

Working as an illustrator enabled Bama to hone his artistic skills, and to develop discipline and good work habits. The pressure of deadlines and the lack of creative freedom, however, grew wearisome. Bama’s marriage to Lynne Klepfer in 1964 changed his artistic path. She encouraged her husband to abandon commercial art for a career as an easel painter. The Bamas also discussed relocating their home away from the distractions of New York City and the illustration community.

In June 1966, the couple visited friend and fellow artist Robert William Meyer, on his Circle M Ranch, near Cody, Wyoming. The area’s beautiful landscape, rugged inhabitants, and mountain solitude offered the quiet refuge for which the Bamas had been longing. In 1968, they left their Manhattan apartment for the solace of a small cabin on Meyer’s ranch.

During his first few years in Wyoming, Bama maintained his illustration career. In 1971, Jim and Lynne Bama moved to a home near Dunn Creek on the Northfork of the Shoshone River, about 20 miles west of Cody. By May, he had completed 18 paintings and sought gallery representation in New York City. With the success of this first gallery show behind him, Bama confidently abandoned his illustration career and became an easel painter.

The artist’s natural talent, academic training, and practical professional experience as an illustrator equipped him with the tools to succeed as an easel painter. Influenced by photography, abstract expressionism, pop art, and illustration, Bama fused these media and styles into an ultra-detailed brand of realism based on complex compositions. Unlike many artists working in the American West today, he steadfastly refused to paint the Old West but instead dedicated his career to painting real people of the modern West. His detailed portraits capture the ethnic and cultural complexity of the American West through people who live simultaneously in two worlds.

Selected Annotated Bibliography on James Bama

Thomas B. Smith, “Native Americans In The Contemporary American West: The Portraits of James Bama,” (M.A. thesis, University of Oklahoma, 2006).

Kelton, Elmer. The Art of James Bama. Trumbull, Connecticut: Greenwich Workshop, 1993.

Bama, James E. The Western Art of James Bama. New York: A Peacock Press/Bantam Books, 1975.

McGehee, Lorry. “James Bama: 20th Century American Realist.” Art West, vol. IV, no. 3, March/April 1981, 32 – 41.

Bergen, Chan. “The Western Art of James Bama.” Western Horseman. June 1980, 62 – 65.

Stavig, Vicki. “James Bama: Portraits Tell the Story.” Art of the West, vol. 9, no. 2, January/February 1996, 24 – 30.