The Curator Responds

Dear readers and patrons,

Thank you so much for all of your thoughtful questions on our collections, gallery displays, and objects. I hope you find our responses helpful. Let’s get to it.

Q: I can find no pictoral references or illustrations as to the logistical method Plains Indians would carry/utilize all their gear, like strung bows, quivers, coups sticks, quirts, war clubs, spears and/or rifles etc. while on horseback…

A. The trouble with art is that more often than not artists take full use of their artistic license when they paint, draw, or sculpt. Even artists that render on-the-scene sketches (which they then elaborate on and convert into paintings or full drawings) are not capturing minute details as much as outlining a particular scene, facial expression, or landscape. The good news is our Plains Indian Museum Assistant Curator Rebecca West has graciously offered some book suggestions that will hopefully answer your question more thoroughly than our art can.

Hassrick, Royal. The Sioux: Life and Customs of a Warrior Society. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1964.

Hansen, Emma. Memory and Vision: Arts, Cultures, and Lives of Plains Indian People. University of Washington Press, 2007.

Her Many Horses, Emil, and Horse Capture, George, eds. A Song For the Horse Nation: Horses in Native American Cultures. New York and Washington, D.C.: National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution in association with Fulcrum Publishing, Golden, CO, 2006.

Taylor, Colin F. Native American Weapons. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001.

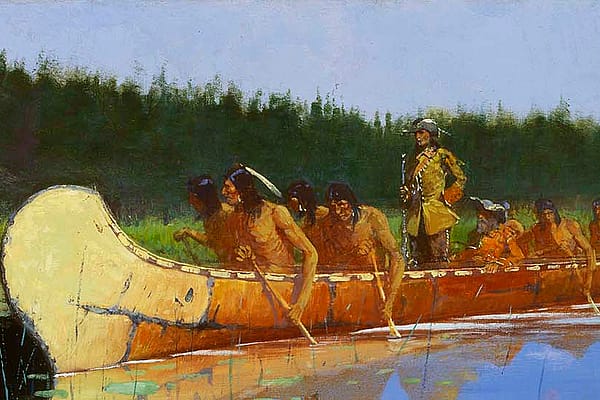

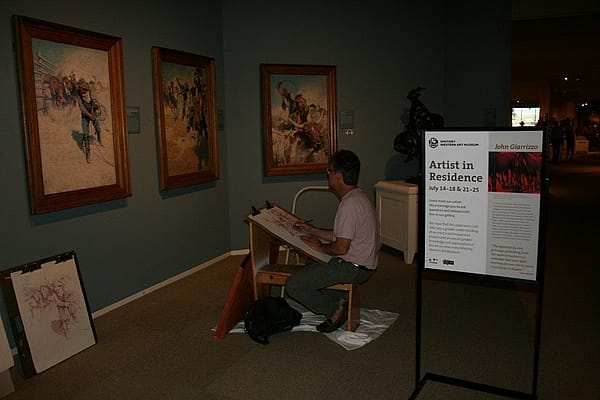

Q: Why does your museum put up more contemporary art than traditional western art? I came to see Remington, Russell, Rungius, etc., not some abstract art.

A: The good news is you can always see traditional art inside the Whitney Western Art Museum. We make sure we always have a robust selection of traditional artists, such as Remington, Russell, and Rungius, on view at all times. We believe that it is just as important to hang works by living artists as those by old masters. The appeal and draw of the West is just as strong today for artists as it was two hundred years ago. We want to showcase traditional and contemporary perspectives and techniques, in order to highlight how the West has changed, progressed, and, in many ways, stayed the same. By juxtaposing artists of different time periods, we can tell the same story in radically different ways or in some cases, remarkably similar ones.

Consider this: if you really don’t like a painting, perhaps you should spend more time with it—get up close, analyze the surface, the technique, the color choices; sometimes the more you look, the more you see, and the more you have to appreciate.

Q: I am fascinated by the tumbleweed sculpture in your gallery, can you tell me more?

A: The tumbleweed sculpture was made by the artist Bale Creek Allen, who lives and works in Austin, Texas. His interest in tumbleweeds comes from his familiarity with them growing up in Texas. To Bale Creek Allen, these are dead objects that once served another function; in their new state, they become something different in the landscape. The bronze tumbleweeds are created through the lost wax casting method. First, the tumbleweeds themselves are coated with a material that hardens into a vessel tough enough to receive molten bronze. After the coating dries, the tumbleweed is burned out in a furnace to leave a detailed impression. Then Bale Creek pieces each individually-cast piece back together to create a whole.

Q: Does the Remington studio contain his personal possessions?

A: It does. Most of the objects on display in the studio were owned by Remington and were used as inspirational props for his art. He purchased most of his studio materials while on trips to the West. A few of the objects, such as the painting easel, are objects that we placed in the studio in order to match old photographs and accounts of his work space, in the few instances that we didn’t own the original object. The audio narration in the studio is meant to be from the point of view of Remington’s neighbor’s wife, and is based on letters and other first-hand accounts and facts we know about the artist, his working method, and his studio space.

Q: How much of your collection is in storage?

A: A large portion of our collection is in storage for many reasons. One: We don’t have enough wall or gallery space to display everything we own. Two: We like to keep a dynamic space, which means our curator makes sure to choose works that will stimulate conversation and thoughtful contemplation within a certain area of the gallery and with nearby works. Three: Most of our works on paper are in storage because they last longer and stay in better condition if they are allowed to rest for longer periods of time. But don’t worry; we want to show you the best works as often as we can, which means the good stuff is almost always on display.

Q: Can you tell me how much my painting is worth?

A: As a museum, it is against our policy to appraise, evaluate, or authenticate works of art (the exception is that once a year we do hold an authentication session for two-dimensional Remington works of art). If you are interested, we do provide a list of local, regional, and national appraisers that may be able to help you. Please send an e-mail of inquiry to [email protected] for this list.

Written By

Emily Wilson

Emily Wilson is the curatorial assistant at the Whitney Western Art Museum. She is a big fan of contemporary art and taxidermy. Living in the West has made her appreciate the region for its artistic and aesthetic draw.