Scots in Wyoming – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall 2010

Scots in Wyoming

By Jeremy Johnston and Chris Dixon

Dol siar . . . heading west . . .

In the songs of the Gaelic bards of old, this idea occurs time and again, often as an image of coming home. If the Viking sagas are to be believed, one such bard may even have been the first “Scot” to sight the American mainland in 985 A.D. That may be no more than a story, but what is certain is that from the seventeenth century onward, Scots, and later Scots-Irish, immigrants played a vital role in the development of America.

In the late 1600s, Glasgow, Scotland, was the European center for the Virginia tobacco trade in America, and Scots Presbyterian dissenters in search of religious freedom established their own colonies in South Carolina and New Jersey. In the 1700s, population growth, agricultural modernization, and political upheaval in Scotland were the driving forces behind more than 50,000 immigrants crossing the Atlantic, and, as the new Republic looked west toward the end of the century, many of the earliest “over-mountain men” settling the Ohio and Tennessee valleys were of Scots or Scots-Irish descent.

It is little wonder, then, that in the 1800s, as the United States expanded into the areas we now think of as the West, Scots were so much to the fore.

William Drummond Stewart, an adventurous Scot

While many Scots came to America to begin a new life for themselves and their families, a few traveled to the West just for adventure and sport. Such was the case for William Drummond Stewart, who arrived in what is now Wyoming in 1833. Stewart was born at Murthly Castle, Perthshire, on December 26, 1795, the second son of Sir George Stewart and Catherine Drummond. Because he was second in line to the family estate, his father encouraged him to enlist in the military, and he did so in 1813. Serving in the 15th King’s Hussars, Stewart fought Napoleon’s forces at the Battle of Waterloo and was decorated for leading a daring charge against the enemy line.

When his father passed away, Stewart inherited £3,000; however, much to his frustration, his older brother was entrusted with the administration and distribution of his inheritance. Stewart’s life also became more complicated when his liaison with a friend’s servant girl resulted in the unplanned birth of his son George. He married the young lady and secured a residence for her and their son in Edinburgh, occasionally visiting them between his various adventures.

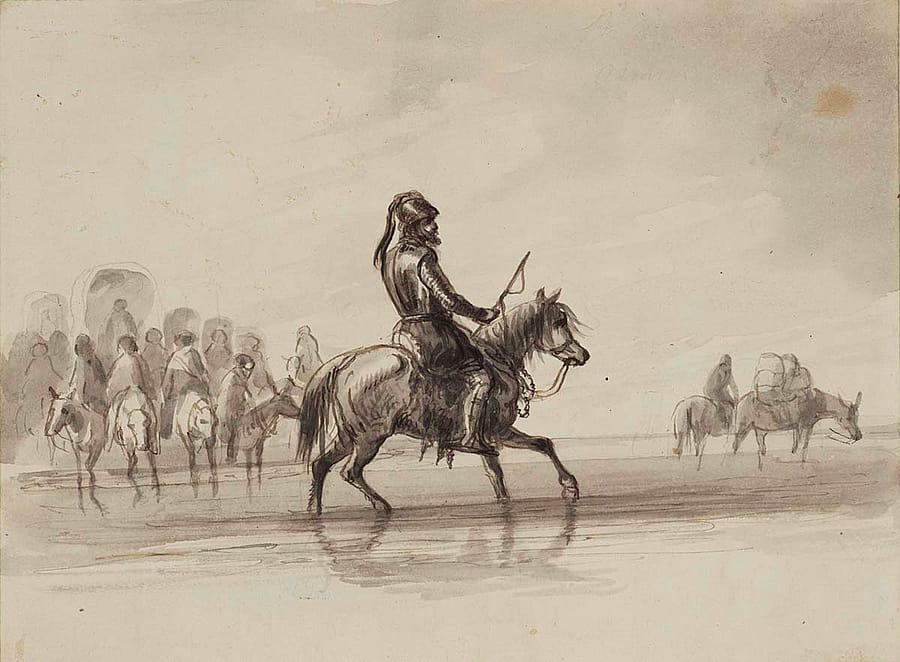

Discouraged by his brother’s control of his inheritance and the management of the family’s estate, Stewart escaped across the Atlantic, where he discovered the exciting lifestyle of the American fur trader and encountered many noted frontiersmen, including William Clark of the Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery. In 1833, Stewart paid $500 to accompany the freighting firm of Sublette and Campbell in their delivery of goods to a site on the Green River in Wyoming for the annual rendezvous. Dr. Benjamin Harrison, the son of future President of the United States William Henry Harrison—whose mother Elizabeth Ramsey Irwin was of Scots-Irish descent—also joined the entourage after his father encouraged him to seek adventure in the West in the hope that the trip would cure the younger Harrison’s drinking problem. Stewart gained the respect of his fellow travelers despite donning formal hunting outfits that greatly amused the trappers.

In the next few years, Stewart found himself in the middle of a number of exciting and historical episodes in the West. First, at the 1833 Green River Rendezvous, a rabid dog bit one of his companions. Shortly after that, his party lost their horses and most of their equipment to a band of Crow raiders. He later met Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spaulding at another Rendezvous, the first Euro-American women to cross South Pass, Wyoming, and travel overland to Oregon—an event then viewed as a significant landmark in opening emigration to Oregon Territory.

At yet another Rendezvous, Stewart witnessed an operation conducted by Dr. Marcus Whitman to remove an imbedded Blackfoot arrowhead from the back of famed mountain man Jim Bridger. During the 1837 Rendezvous, the Scot presented Bridger with polished steel body armor and a plumed helmet, two elements of the uniform of the British Life Guards. Bridger put on the armor and helmet, and clanked around the rendezvous amusing his drunken companions and Alfred Jacob Miller, an artist in Stewart’s employ, who sketched the unusual scene.

When he learned of his elder brother’s death, Stewart returned to Scotland in 1839, but he was back in America in 1842 for a final get-together with his former Rendezvous companions. Sir William Drummond Stewart spent the remainder of his life on his Scottish estate gazing upon the paintings of Alfred Jacob Miller and recalling his exciting days in Wyoming. He died in 1871.

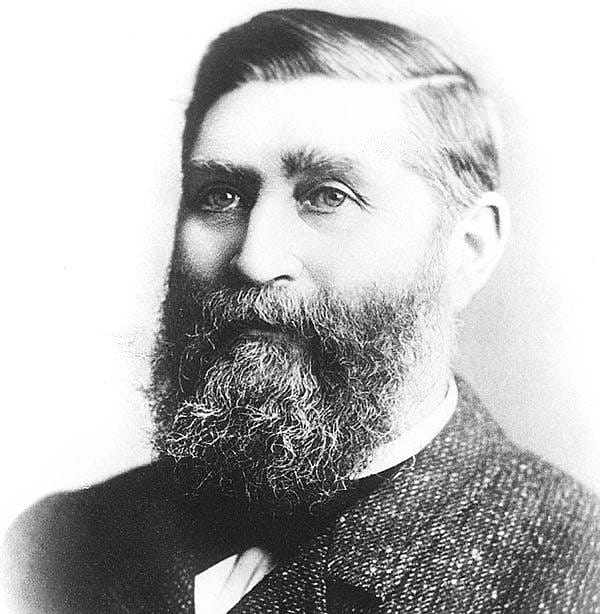

Thomas Moonlight, a soldiering Scot turned politician

A few years after Stewart’s escapades, Thomas Moonlight, another Scot, arrived in Wyoming to advance Euro-American settlement. Born in Forfarshire in 1833, Moonlight ran away from home at the age of thirteen and became a sailor on a vessel en route to Philadelphia. In 1853, after working in various settings, including a glass factory in New Jersey, Moonlight enlisted in an artillery unit of the United States Army and served on the plains of Texas, in the Seminole War in Florida, and in Kansas.

Moonlight briefly left the military in 1858 and settled on a farm in Leavenworth County, Kansas; however, the outbreak of the Civil War called him back to service. He joined the 11th Kansas Infantry as a lieutenant-colonel and in 1864 was promoted to full colonel. The following year, the 11th Kansas Infantry marched to Fort Laramie, and Colonel Moonlight found himself in command of that Wyoming military outpost attempting to curtail Indian raids in the wake of the Sand Creek Massacre in southeast Colorado.

Using Jim Bridger as his guide, Moonlight led five hundred cavalrymen west from Fort Laramie to the Wind River Valley hoping to surprise a large Cheyenne camp. After a grueling 450-mile march through a cold Wyoming spring without encountering any Indians, a disappointed Moonlight returned to Fort Laramie. Shortly after this unsuccessful expedition against the Cheyenne, two Oglala Lakotas named Anog Numpa, or Two Face, and Si Sapa, or Black Foot, arrived at Fort Laramie escorting a captive white woman and her child.

Without trial or questioning, and despite the objections of many—including the white captive herself—Moonlight ordered the two men to be hanged by the neck with chains. The bodies of Two Face and Black Foot remained suspended for months from the scaffold on the bluffs near the fort. After this infamous hanging, Moonlight led another force against the natives hoping to win a great victory; however, as the horses were grazing, Indian raiders seized the opportunity and drove most of them away, leaving Moonlight and his men to endure a long, humiliating walk of more than a hundred miles back to Fort Laramie.

When the Civil War ended, Moonlight entered politics as a Republican. In 1867 he was appointed United States Collector of Internal Revenue and in 1868 was elected Secretary of State for Kansas. In 1870, he left the Republican Party over the issue of prohibition and was elected to the Kansas State Legislature as a Democratic senator. When Democratic President Grover Cleveland appointed him Territorial Governor of Wyoming in 1887, Moonlight vowed to protect common settlers from the powerful cattle barons of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association. Governor Moonlight traveled more than 1,200 miles throughout Wyoming that year, meeting settlers and hearing their complaints. He received a warm welcome in Johnson County, soon to be the focus of an infamous range war.

Moonlight’s relationship with the Wyoming Territorial Legislature was a difficult one, resulting in seven vetoes and earning him as many enemies as supporters. When the legislative session ended, Moonlight published an explanatory pamphlet titled “Seven Vetoes by Thomas Moonlight” hoping to garner more support among the residents. However, his mishandling of the organization of Sheridan and Converse Counties cost him political support, especially in his former stronghold of Johnson County.

When Republican Benjamin Harrison was sworn in as President of the United States in 1889, he replaced Moonlight with Republican Francis E. Warren, much to the relief of many Wyoming residents. In 1892 Grover Cleveland won the presidential election in a rematch against Harrison and rewarded Moonlight by appointing him Minister to Bolivia, a position he held for four years. On February 7, 1899, Thomas Moonlight passed away in Kansas.

Cattle Kate Watson, not really a rustler?

Cattle raids and rustling played a major role in Scotland’s past, with border reivers (border raiders) and Highland clansmen raiding their neighbors for cattle. When the quarrel between Wyoming homesteaders and cattle barons boiled over into an all-out range war, many Scots joined the fray. Ellen Liddy Watson, daughter of Thomas Lewis Watson of Hamilton, Scotland, had the unfortunate distinction of becoming the first woman hanged in Wyoming, unfairly earning the moniker, Cattle Kate Watson.

Current scholarship reveals that Ella Watson was a typical woman homesteader who worked a variety of jobs after her first marriage ended in divorce. Watson became involved in a relationship with a widower by the name of James Averell, whose mother was a Scot. Very likely, Averell and Watson were, for all practical purposes, husband and wife, but Watson retained her maiden name to secure additional acreage as a single woman homesteader. Unfortunately, Averell and Watson’s homesteads, located west of Casper, Wyoming, were too close to the ranchlands of Albert Bothwell, another whose surname suggests a Scots heritage. Averell and Watson were homesteading in the wrong place at the wrong time.

To make matters worse, Averell was outspoken in his opposition to the domineering cattle barons. On July 20, 1889, a group of six men, led by Bothwell, arrived at Watson and Averell’s ranches, accusing both of rustling cattle. They abducted the two homesteaders and later lynched them along the banks of the Sweetwater River, despite the valiant efforts of another settler of Scots descent, Frank Buchanan, who fired his rifle at the lynching party. Buchanan and other witnesses to the hanging either died under mysterious circumstances or completely disappeared; thus, the lynching party escaped any punishment for the crime.

Fearing negative publicity resulting from the hanging of an innocent woman, the Wyoming Stock Growers Association hired a Cheyenne-based news reporter, Edward Towse, to write a sensational article accusing Ella Watson of being a mean-natured and violent prostitute who exchanged her services for rustled cattle. He also noted that Cattle Kate was well known for using rough language. Unfortunately, the libelous story became a popular Wyoming legend and for years the innocent Ella Watson was characterized as the infamous Cattle Kate.

John Clay, a Scot in the Wyoming Stock Growers Association

John Clay, Jr. was prominent in furthering Towse’s story, and in his memoirs, Clay accused Watson of being “a prostitute of the lowest type…she was common property of the cowboys for miles around.” Clay, who hailed from Winfield in Perthshire, acted as a ranch manager in the development of land in Wyoming for Scottish investors, including the extensive holdings of the Swan Land and Cattle Company in the east-central part of the state. Through his expertise, Clay became the president of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association and furthered its efforts to eliminate the so-called rustlers, who were in many cases small homesteaders like Averell and Watson trying to build up their own ranches.

In 1892, a group of armed men unsuccessfully invaded Johnson County hoping to rid the territory of this rustling element and its supporters. John Clay later claimed that he knew nothing of the invasion—eventually called the Johnson County War—and asserted that he took no part in planning any of the violent acts connected to the Wyoming range war. He did, nevertheless, defend the actions of the invaders in his address to the 1893 annual meeting of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association. He expressed his “respect for [their] manliness, their supreme courage under the adverse fire of calumny and the usual kicking a man gets when he is down.” Clay also stated, “There will be a day of retribution.” Clay, Scottish promoter of the Wyoming cattle barons, died on St. Patrick’s Day in 1934.

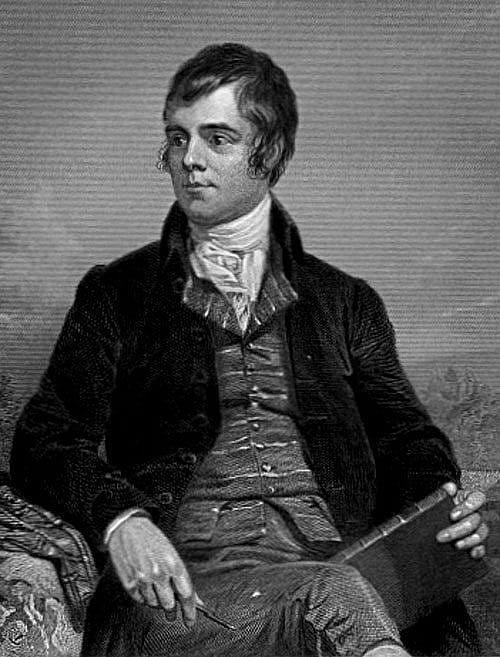

Robert Burns

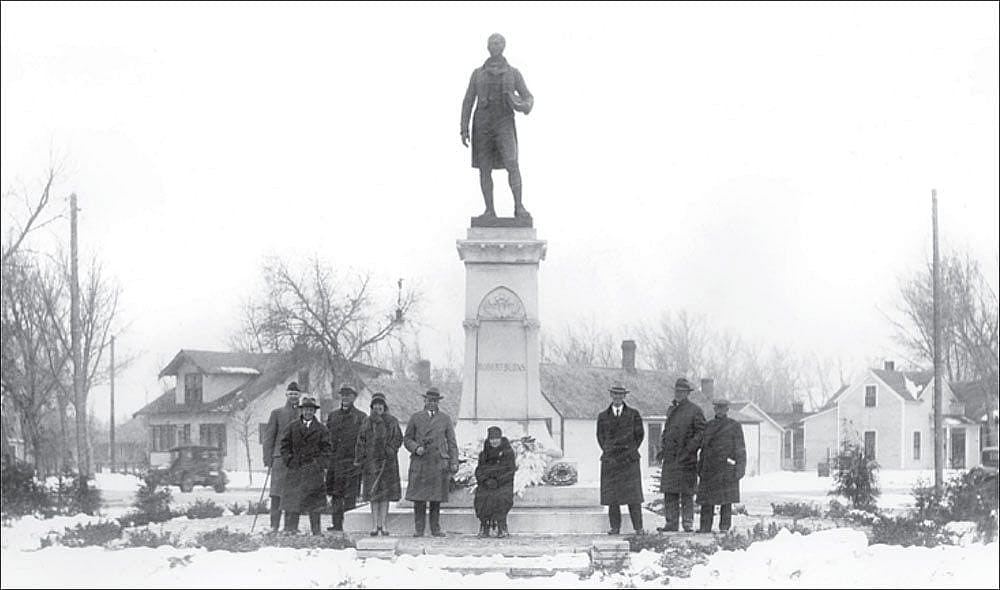

Five years earlier, Wyoming had marked its historic links with Scotland in monumental fashion when Henry Snell Gamley’s bronze statue of Scottish poet Robert Burns was unveiled near the Capitol Building in Cheyenne. In 1794, to mark the occasion of George Washington’s birthday, Scotland’s national bard had written the famous words:

But come, ye sons of Liberty,

Columbia’s offspring, brave as free,

In danger’s hour, still flaming in the van,

Ye know, and dare maintain,

The Royalty of Man!

Burns could not have predicted that as America’s westward progress came to Wyoming, so many of those“flaming in the van” would be his fellow Scots.

Former Northwest College Assistant Professor of History Jeremy Johnston recently joined the Buffalo Bill [Center of the West] staff as Managing Editor of the Papers of William F. Cody [and more recently Curator of the Center’s Buffalo Bill Museum]. A graduate of the University of Wyoming with bachelor’s and master’s degrees in American history, Johnston taught a variety of history courses at Northwest College in Powell, Wyoming, including American History and the histories of Wyoming, Montana, Yellowstone National Park, North American Indians, and the American West.

Chris Dixon, senior research fellow in the School of Humanities at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, Scotland, is a member of the United Kingdom’s Chartered Institute of Linguists and holds two master’s degrees from Glasgow University. Dixon recently edited Four Years in Europe with Buffalo Bill, a book by Charles Eldridge Griffin, originally published in 1908. The book, produced by the University of Nebraska Press, is featured on page thirty of this issue of Points West and is now available. Dixon is an associate editor of the Papers of William F. Cody.

Full Image Credits:

In Greeting the Trappers, ca. 1837, Alfred Jacob Miller (1810–1874) portrayed Stewart meeting trappers at the Rendezvous. Watercolor on paper. Gift of The Coe Foundation. 8.70

Alfred Jacob Miller (1810–1874). Jim Bridger in a Suit of English Armor, 1837. Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha Nebraska. JAM 1988 10 28 A

Thomas Moonlight portrait, no date. Wyoming State Archives, Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources. Sub Neg 2641 derivative.

Ella “Cattle Kate” Watson on horseback. Wyoming State Archives, Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources. Sub Neg 4104

William Henry Jackson (1843–1942), photographer. Looking east from Independence Rock, Wyoming, with the upper end of Pathfinder Reservoir visible in the distance, ca. 1870. Cattle Kate’s homestead was situated just northeast of Independence Rock. National Archives and Records Administration, Hayden Survey series. NWDNS-57-HS-284.

John Clay, Jr., ca. 1890. Wyoming State Archives, Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources. Thorp Neg 195.

The dedication of the Robert Burns statue in Cheyenne, Wyoming, on November 11, 1929. Wyoming State Archives, Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources. Sub Neg 13178

Robert Burns, 1787. From Evert A. Duyckinick, Portrait Gallery of Eminent Men and Women in Europe and America. New York: Johnson, Wilson & Company, 1873. Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, the University of Texas at Austin. Wikimedia Commons.

Post 005

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.