Twenty-five years celebrating the annual Plains Indian Museum Powwow – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2006

By Rebecca West

Plains Indian Museum Curator

Editor’s note: On the eve of the 33rd Annual Plains Indian Museum Powwow in 2014, this article looked back at the 25th.

Periodically, the Plains Indian Museum staff fields the question “What makes your Powwow unique and special compared to other powwows?” Typically, the question is asked by those who have never attended the Powwow. However, once they do, the answer unfolds before them. The Annual Plains Indian Museum Powwow has been celebrated for 25 years each summer in Cody, Wyoming, and now attracts 300 dancers from all over the United States, nearly 5,000 visitors, and can be considered the largest, longest running public program at the Buffalo Bill [Center of the West].

What is special about the Powwow is not measured in years, numbers, or aesthetics, but in the relationships it has fostered since it originated in 1981. The Plains Indian Museum Powwow began as a small gathering of dancers, a single drum group, and mostly local spectators at the Cody High School football fields. The Robbie Powwow Grounds, its present location, did not yet exist; and the stage consisted of a flatbed trailer. The story of the lone drum group has become somewhat of a Center legend: The drum group’s car broke down in Cody; they heard about a powwow in town and asked if they could stay and drum.

What happened in 1981 was the beginning of an amazing synthesis of culture and community as the Powwow began to grow and take on an identity as “The Cody Powwow.” This Powwow was different for many reasons. It was not held on or near an Indian reservation, as are most Plains powwows, and it was not an Indian community event or a large-scale competitive powwow on the summer “powwow circuit.” Dancers had to travel to a fairly remote locale to a little known event—reasons that should have kept them away. But the dancers continued to come, probably due to the Powwow’s relaxed, low-key nature. It became known as a family event, one where attendees could enjoy the company of friends and relatives in a pleasant setting.

The dancers and the Indian community were the first priority for the Center staff and the group of volunteers working on the event. As the Powwow became established within the regional Indian communities as an annual event, it has also maintained its status as a competitive, intertribal powwow. Although the size of the Powwow increased exponentially in 25 years, it is still a celebration of cultural traditions for the dancers, drummers, and their families. The difference today lies in the fact that the participants share their traditions with a much wider audience of thousands of visitors.

The addition of the Robbie Powwow Gardens in 1987 contributed immeasurably to the expansion of the Powwow. The late Joe Robbie, former owner of the Miami Dolphins football team, donated funds for the construction of a powwow arena along with surrounding gardens and buildings. The grounds opened for the 7th Annual Plains Indian Museum Powwow and featured a beautiful outdoor amphitheater setting with a stage and concession stand. Moving the Powwow to the Historical Center grounds gave it a setting of its own, which further developed the Powwow’s positive status as both a celebration for participants and a local cultural event for visitors.

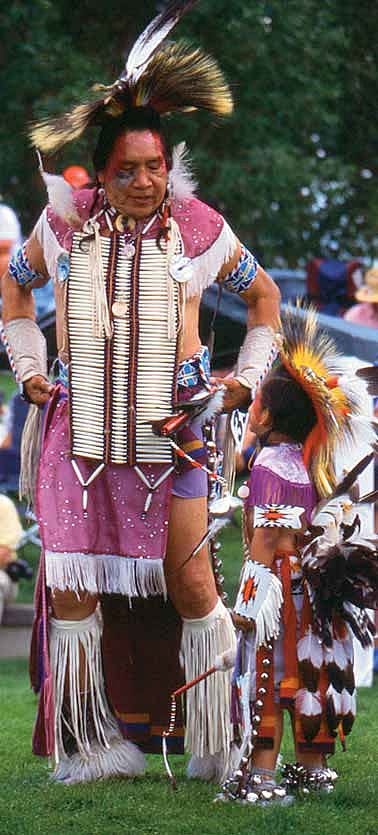

The Powwow has always been a gathering place for multiple generations, and remains that way today. Participants have the opportunity to renew family ties and friendships, and to share traditions with one another. Because the Powwow has dance categories for all ages, tiny tots (6 and under) to golden age (65 and over), as well as social dances, it is not unusual to see entire, extended families attending and participating in one way or another. Mothers and siblings accompany babies, toddlers and preschoolers in tiny tots, and grandparents, if not competing, are watching the dancers and supporting their families from outside the dance arena. Drum groups often have younger singers sitting in to listen or to help sing.

Emma Hansen, curator [now Curator Emerita and Senior Scholar] of the Plains Indian Museum, recognizes the significance of the Powwow to families. “Some teenagers or young adults may have come into the arena and had danced for the first time years ago at this Powwow,” she remarked. “Or, families may have celebrated an important milestone such as a child recovering from an illness or embarking on a special journey at the Powwow. The Powwow provides a place to recognize those accomplishments.”

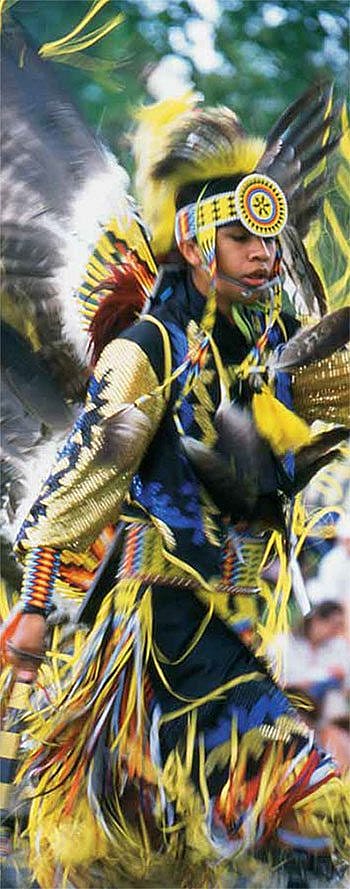

The Plains Indian Museum Powwow—and powwows in general—are not a static tradition. Dancers have a place to show unique artwork and materials on clothing. Although each dance category has traditional aspects that dancers follow, there is room for individuality.

The team dancing competition at the Plains Indian Museum Powwow has become especially dynamic in recent years as teams tell dramatic stories through their dances. It is a forum, unique to this powwow, which allows for more personal innovation in the dances than is typically seen. Teams are able to combine male and female dancers, and can add drama and elements of humor to their dances. This is a sign the dancers are making the Powwow their own. Families sponsor specials and giveaways as a way of honoring individuals or families. By doing this, participants help create the identity of the Powwow as opposed to simply attending.

Maintaining a balance between a powwow that provides a positive experience for Indian participants, and an exciting, educational experience for an audience of thousands is challenging. “The Powwow may seem to many onlookers as a colorful and entertaining performance featuring singers and dancers in beautiful regalia,” Hanson notes. “The Powwow, however, has a deeper significance for Plains Indian people as a powerful manifestation of their heritage, cultural histories, and traditions as well as a contemporary expression of their arts.”

For a powwow to be truly authentic, traditional aspects of the powwow must remain intact. There are important spiritual and ceremonial aspects to be respected during the course of any powwow. To aid in their understanding of the various Plains Indian Museum Powwow activities, visitors are taught (through the emcee and programs, such as the Learning Tipi) about the history of the modern day powwow, which emerged from over a hundred years of ceremonial and social dance traditions and gatherings of Plains tribes.

Arthur Amiotte, Plains Indian Museum Advisory Board member, explains the significance of pre-powwow gatherings. “…this was the occasion for the people to adorn themselves in traditional beauty and dance regalia, thereby affirming their identities and pride in who they were. At this time, these gatherings were not called nor known as powwows,” Amiotte explained. “This term would not become popular until the late 1950s. Competitive dancing did not take place. These were tribal gatherings, shows of solidarity, affirmation, and renewal of relationships.”

Values of pride, solidarity, and the importance of tribal and family relationships still exist. In fact, they are the driving force that keeps the powwow tradition alive. Visitors are reminded that these traditions didn’t materialize overnight, but were born and nurtured through human interaction. By understanding the history and values behind what they are witnessing, visitors to the Plains Indian Museum Powwow can better appreciate the role of the powwow in Indian cultures

The relationships formed over the years have kept the Plains Indian Museum Powwow vital. Behind the flash and energy of the event is a Powwow Committee, which consists of Plains Indian Museum Advisory Board members and staff, Powwow officials, tribal members, and volunteers. This, however, is more than a committee. It is a group of individuals who truly enjoy the Powwow and want to ensure its continued success.

Volunteers like June and Arne Sandberg lent their hands to the Powwow in its beginnings and continue to watch it change. “It has been interesting to see the local Powwow grow over the years,” said Sandberg. “It has served as a premier cultural event and as an excellent learning experience, as it was originally intended to be. It is an event that seems to amaze visitors; they are grabbed as they pass by with the beauty of the pageant. Every year it seems to get a bit better.”

Dancers, drummers, vendors, and members of the Indian communities who have been attending for so many years also feel comfortable offering opinions and advice about what they’ve enjoyed, and what may need to change. There has been much trial and error, but each year the Powwow is reviewed and fine-tuned to make it successful from the standpoint of everyone involved.

The Powwow has given both Indian and non-Indian peoples the opportunity to connect to something beyond their everyday life experiences. Whether it is a family connection, a new or renewed friendship, or an appreciation of one’s own or another culture, the Powwow is a celebration of these opportunities. In its twenty-fifth year, the Plains Indian Museum Powwow is a living tradition that will unfold into the next century.

About the author

At the original publication date of 2006, Rebecca West was the curatorial assistant for the Plains Indian Museum. She became curator in 2014, and as of 2019, serves as Curator of Plains Indian Cultures and the Plains Indian Museum, as well as the Collier-Read Director of Curatorial, Education, and Museum Services.

Post 028

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.