“That Hymn of Divine Crudeness?” Frederic Remington the Painter

Peter H. Hassrick

Frederic Remington was remembered at the time of his death in a rather singular way. His image was that of a staunchly independent artist, uniquely American in character and expression, who had dedicated his relatively short career to portraying the historical themes of Western life. He was known to have deliberately sacrificed grace for the pursuit of truth in his art and left behind a body of work that the art critics and dilettantes alike categorized as rugged and overtly masculine. A eulogy in the San Francisco News Letter (January 8, 1910) applauded his celebration of “that hymn of divine crudeness, vitality, freedom and power the West amid its flaunt of color has sung since birth.”[1] Seventeen years later, in his History of American Painting, Samuel Isham would conclude of Remington’s work that it spoke but one language and focused unswervingly in a westward direction.

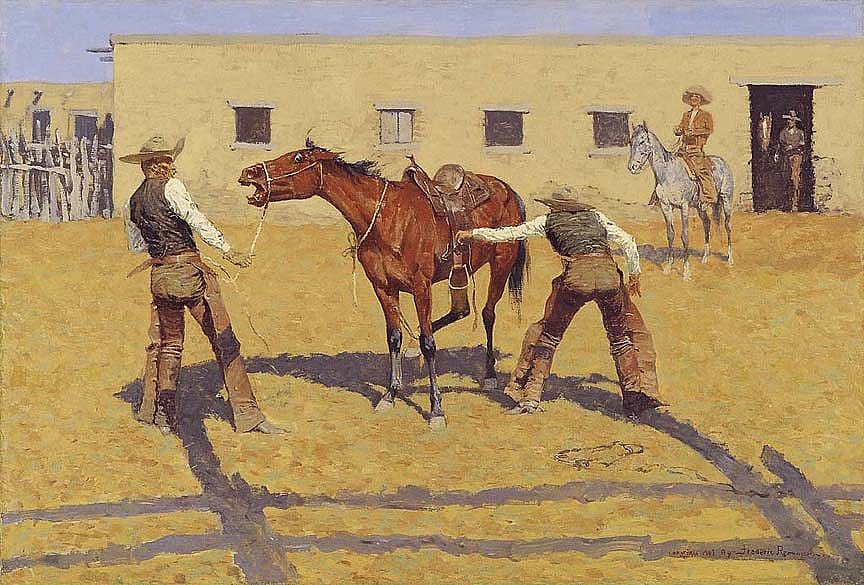

“The raw, crude light, the burning sand, the pitiless blue sky, surround the lank, sunburned men who ride the rough horses and fight or drink or herd cattle as the case may be.”[2]

These were summary testaments to a life’s work that had spanned only twenty years. They held forth the image of a man whose art had garnered universal acceptance …. an image that has remained essentially intact to the present day, but an image that has proven sorely wanting in understanding and appreciation of Remington’S true contribution to American art.

This is not to say that Remington’s paintings did not recite such raw and abrasive themes or echo such crude and sunbaked sentiments. It is important to recognize, however, that these elements comprise but a pan of a far more subtle and complex creative history as illuminated in the pages of this catalogue raisonné. For while his paintings did often embrace a pitiless world, they were certainly not limited to such a perspective, nor did such elements actually form the most striking aspect of his production as a painter.

There are, in fact, five or more distinct periods of Remington’s painting career, each driven by clearly distinguishable motivations and aspirations, and each recognizable by marked differences in technique and style. Most observers acknowledge only the earliest phase of the artist’s aesthetic development which, because it was so boldly presented and expansively distributed, became his hallmark and subsequent measure.

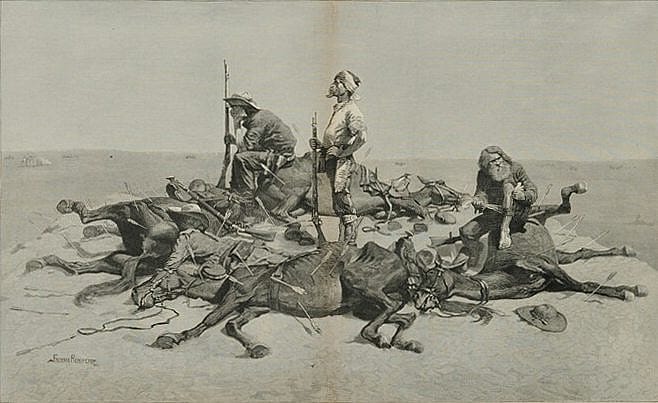

Although he was born in 1861, Remington did not make his real debut as a painter until he was in his late twenties. In 1889, only three years into his painting career. Remington’s work had generated sufficient attention to propel him to the international level: five of his paintings were juried into the American Exhibition at the Paris Universal Exposition. The largest and most fully realized of these paintings, The Last Lull in the Fight (1889, Figure 1), was awarded a Silver Medal. A few months later he exhibited his masterwork of that year. A Dash for the Timber (Figure 2) at the National Academy of Design in New York . It was accorded special favor as the most

popular piece in the autumn exhibition.

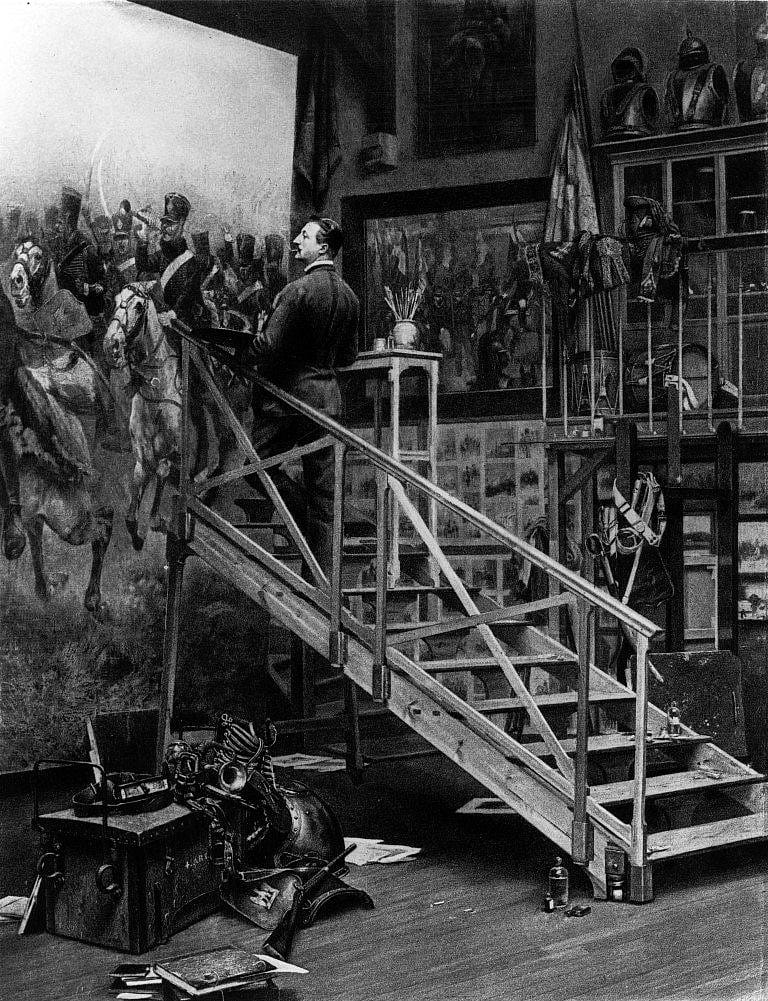

These two paintings fit perfectly into the descriptions of his work which appeared in his obituaries twenty years later. They were sufficiently academic to win a place on the gallery wall, yet strangely violent and experiential compared to those paintings which hung beside them. Remington’s works pridefully espoused what he perceived as American truths about the rugged frontier life of his country. Yet in style they were unabashedly European. Remington had minimal training, a year-and-a-half at Yale’s School of Fine Arts and a couple of months at the Art Students League, and boasted of professional ascendancy without the normally prescribed European tour. Despite these circumstances, Remington had openly assimilated vast reservoirs of visual material from both native and foreign (especially French and Russian) mentors and contemporaries, including Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier, Jean-Baptiste-Edouard Detaille (Figure 3) and

Alphonse-Marie de Neuville.

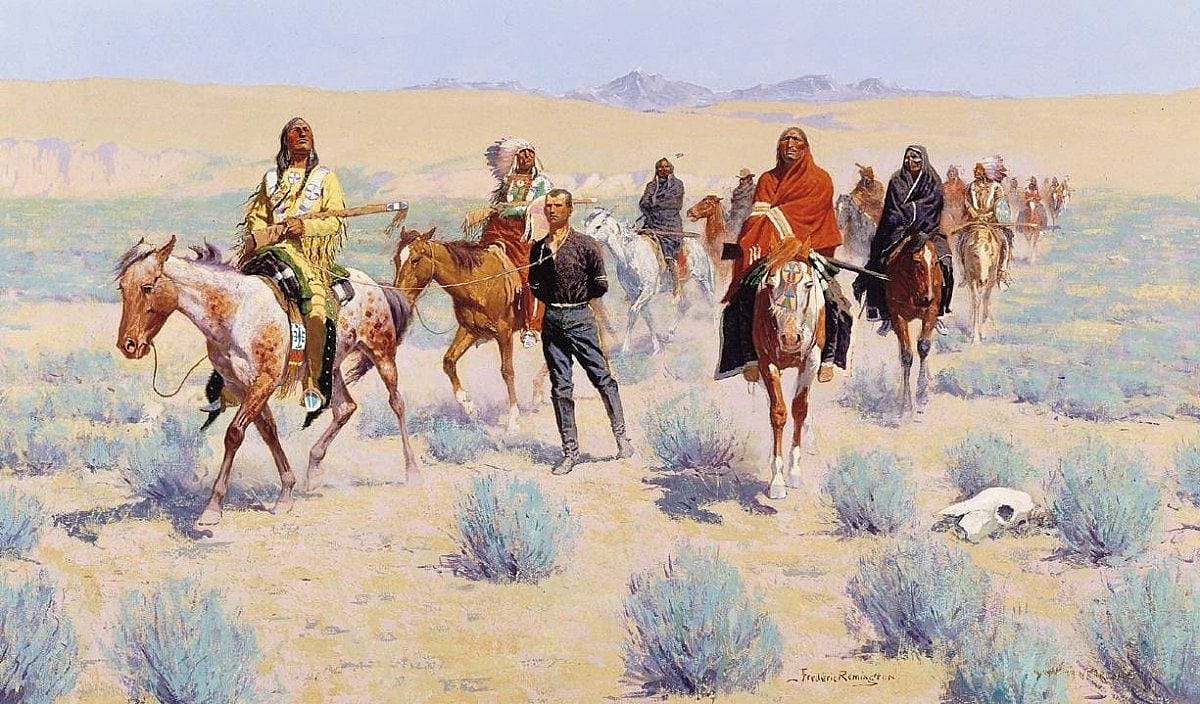

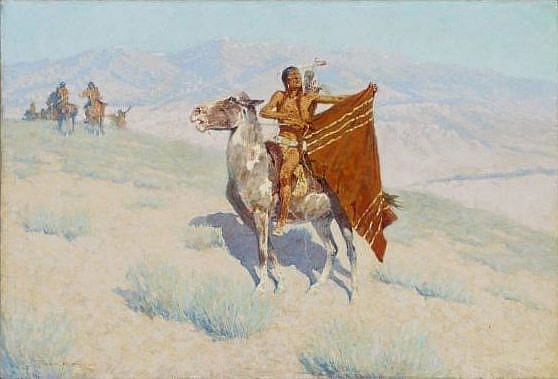

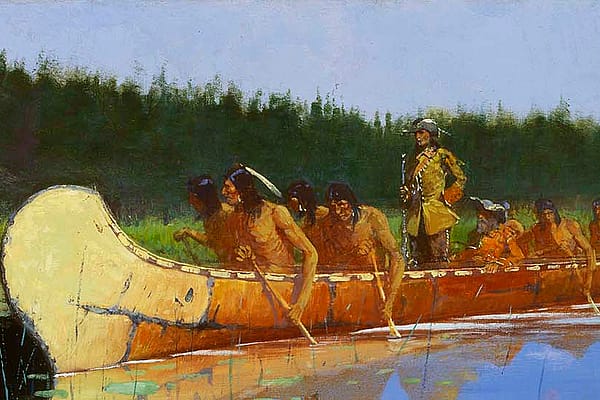

The paintings were tightly drawn, brushed with hard color and fashioned with explicit narrative ends in mind. They portrayed simple men in dire confrontational situations which portended strongly fatalistic consequences. Remington’s was a Darwinian outlook. He celebrated the contest of Euro-American white forces against an untamed frontier West. His heroes were more symbols of the frontier’s demise rather than harbingers of hope for a new life or world. And finally, whether he pictured cowboys, Indians or soldiers, his was a martial perspective (Figure 4). He harbored a steady fascination for the vagabond nature of the Western man and crafted an image to suit: a man with a hardened visage who had an unerring resolve to fight against the elements and a disciplined disregard for the attendant dangers.

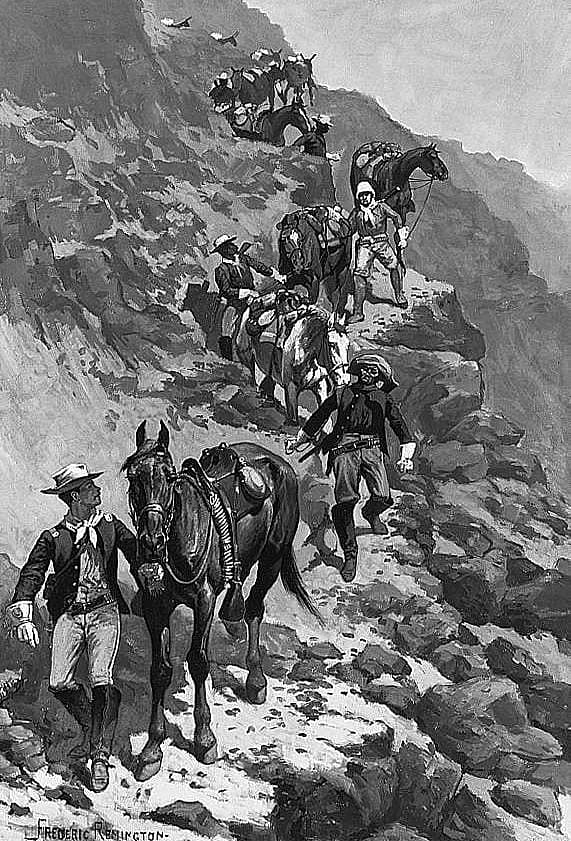

The second phase of Remington’s career as a painter coincided with and complemented his fine art work. His penchant for narrative made him a facile and productive illustrator. His father, Seth, had been a journalist and Remington enjoyed combining his own inclinations for collecting visual material with his father ‘s skills at telling the story. He relished the opportunity of going into the field as an artist-correspondent (Figure 5), in search both of adventure and of topics salable to eager eastern audiences. His introduction to the public in the pages of Harper’s Weekly and other popular journals of the day propelled Remington into the limelight within a few short years. He soon became “America’s man” for Western subjects. His work in illustration was generally produced either en grisaille or with a relatively monochrome palette. In the early years his figures were hard and brittle, but their contours gradually softened and the modeling became lively and fluid with a few years of practice and development. Such work became somewhat routine for him after a while, and he was able, as a consequence, to produce a substantial body of work for illustration during the 1890s.

Remington’s growth within this discipline came both as a result of the continued application of his artistic talents and through a fortuitous exposure to writers with whom he collaborated, and art editors for whom he worked. Although mostly Western in nature, a broad array of assignments came his way, challenging him to sustain his forthright, clear visual interpretation of life in America.

In 1899 Remington entered his last painting at the National Academy of Design. He had hoped to win official approbation with his submission of Missing (1899, Figure 6) to the Academy’s yearly exhibition, as he had for the previous ten years. Despite his patience, the country’s leading arbiter of artistic taste did not deign to confer on him full recognition in the form of membership. He thus turned his back on the Academy, refusing to participate ever again in its exhibits.

However the Academy’s spurning of Remington ‘s talents did ultimately have a beneficial effect on the artist. The rejection forced him to reconsider some of his working methods and artistic formulae, particularly his use and handling of color. That propelled him into the third phase of his painting career. Without relinquishing his commitment to figure and narrative painting, he awakened to a new sensitivity to the color and treatment of light. A letter of November 1900 to his friend and associate, Howard Pyle, revealed the nature of this new artistic quest:

Just back from a t rip to Colorado and N. Mexico.

Trying to improve my color. Think I have made

headway. Color is great—it isn’t so great as drawing

and neither are in it with Imagination. Without that a

fellow is out of luck.[3]

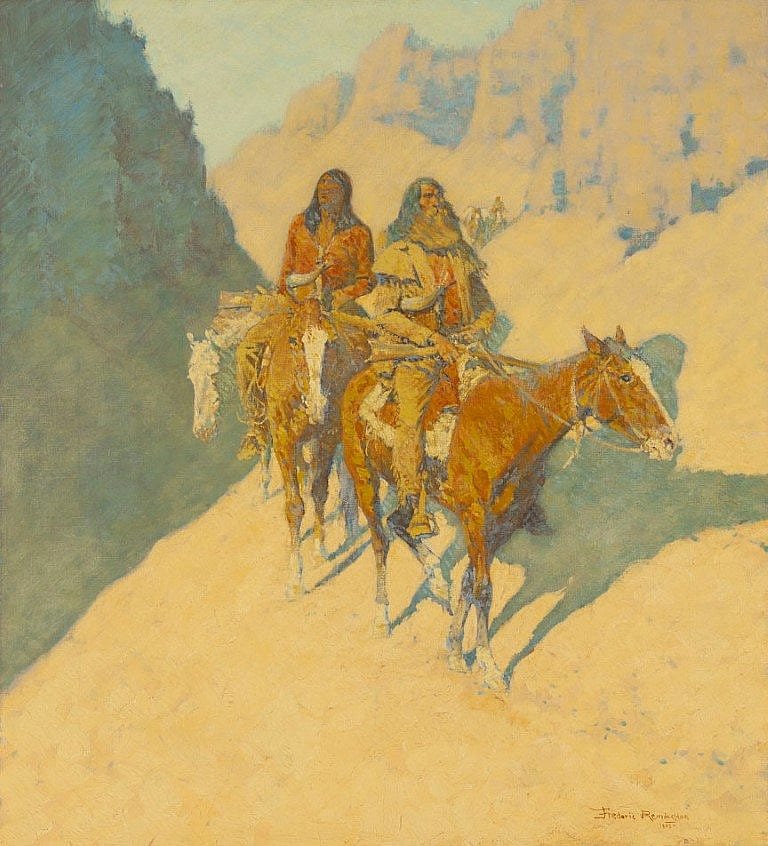

Remington had long been an acute observer of color, but he had suffered criticism for presenting Western color and light uncompromisingly as he found them in nature . . . more prodigious than harmonious. His impression of the light and chroma of northern Mexico, recorded as early as 1895 in his book Pony Tracks, reveals the genuine clarity of the artist’s perceptions in this regard.

We have the inspiring vista of Chihuahua before us all the time.

It is massive in its proportions and opalescent in color. There are

torquois [sic] hills, dazzling yellow foregrounds—the palette of

the “rainbow school” is everywhere.

As Remington expanded his observation and use of color during the early years of the new century, another development occurred to encourage this fresh pursuit. The advent of mechanical color reproduction in the magazine industry provided him with a major opportunity in 1903. Collier’s magazine offered him a contract, which he accepted, to provide color images for full and double-page illustrations (Figure 7). It was an exclusive arrangement and allowed him to select subjects of his own choosing, associated with no accompanying story. This was painting for the sake of painting, and it freed Remington’s talent and imagination for the next five years to explore broad themes of American history, westward expansion, Adirondack and North Country life, and Indian lore.

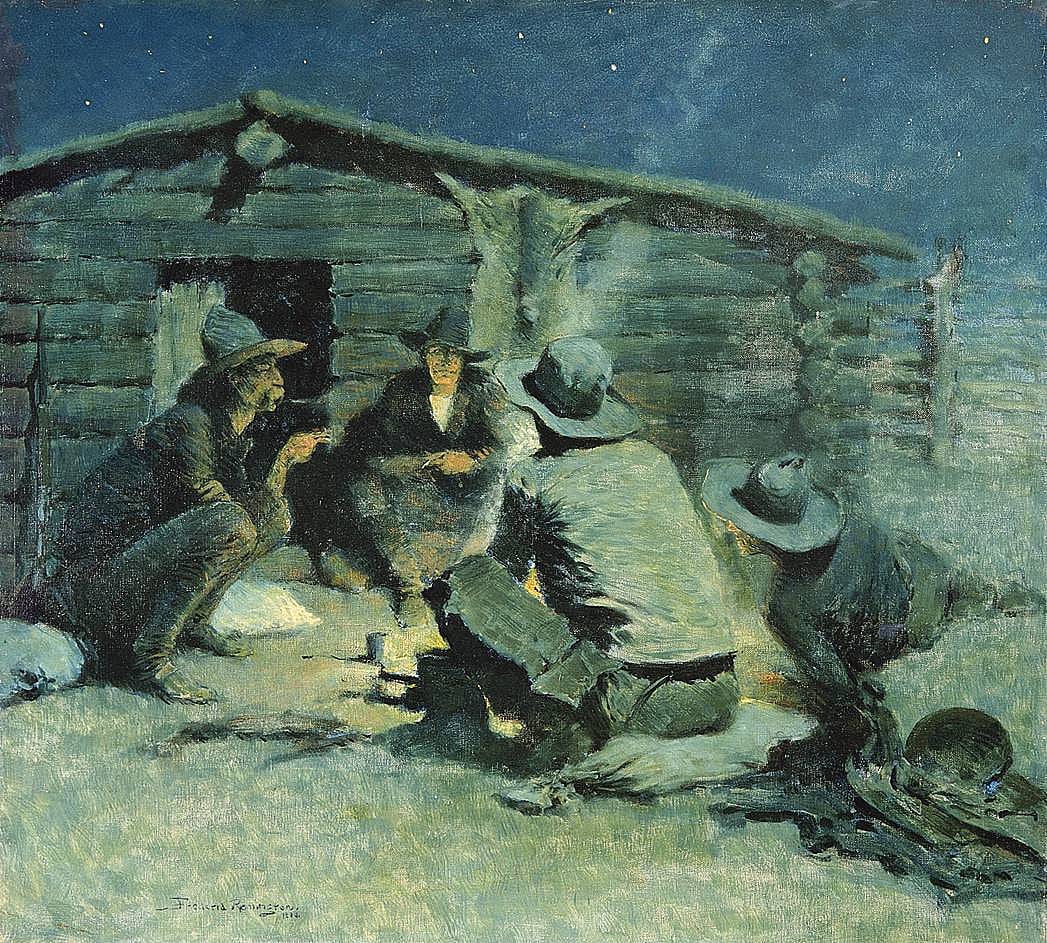

These were years of stylistic experimentation during which Remington attempted to soften his forms and render more harmonious the various elements of his paintings. Success came first with scenes that depicted nocturnal light. By reducing the range of brilliance in his works and attempting to capture the subtleties and mood of night-time effects, he imbued his scenes with a new sense of quietude (Figure 8). The violent, confrontational, Darwinian essence of his earlier oeuvre was gradually replaced by a search for elements of unity between man and nature.

Experiments and success with nocturnes eventually led to an alteration in the way he perceived and painted daylight as well. Increasingly through the first decade of the 20th-century he identified with the vision and energy of America’s nascent practitioners of Impressionism, the Ten. Befriending the early champions of that school (Twachtman, Weir, Reid, Hassam and Metcalf among them) and assiduously following their leads, Remington emboldened his brushwork and reduced the values in his palette. Ultimately he slipped into their patterns and comfortably adopted the aesthetic of those fellow painters of light.

This was a brief interlude, about a year near the end of his life, and the results were uniquely Remington’s. Although he adopted the Impressionist idiom, he brushed it onto canvases that still reflected a resolute devotion to narrative tradition or what Remington called “imagination” (Figure 9).

By 1903, the same year that he signed on with Collier’s, he also began the fourth phase of his painting career, experimenting with subjects that diverted him from purely figurative work. Under the spell of the Impressionists, he began to acquire a taste for landscape painting. A Remington anecdote published by Perrington Maxwell in Pearson’s Magazine (October 1907) explains the transformation under way with the artist during these years.[4]

An art editor of one of the greatest American magazines

asked me some four years ago why I didn’t go West oftener.

“What for?” I questioned. “To collect material,” he answered.

But I said nothing. It would have taken too long to make him

understand. That show the popular misconception. I go West

now every year, but only to paint landscapes—not to collect material.[4]

The objects and artifacts, the drama and characters of the West had lost their hold on Remington, to be superseded by more universal and enduring elements of nature’s light, mood and form. These began to fill his canvases and excite his creative energies as in his painting, Shoshonie (Figure 10).

The last chapter in the story of Remington as a painter coincides with the last chapter of his life. Before his premature death in 1909 at the age of forty-eight, he had converted from a brief devotion to the light of the Impressionist order to the ideational synthesis and decorative spiritualism of another school, the Symbolists. Grasping for a union of painterly harmony, emotional mystery and human story, Remington produced such works as The Cigarette (1909, Figure 11). This and similar paintings of the period were typically somewhat washy, poetic pieces suggesting a resolution to the disquieting themes he had portrayed in earlier years.

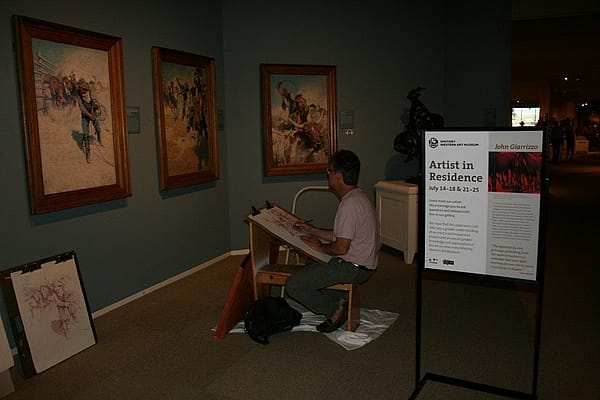

Remington, who had embarked on his career as a painter twenty years before—an illustrator for the popular journals of the day and a young realist painter who won high praise in Paris—came by the end of this life to be recognized as one of the foremost painters in America. Art critic Gustav Kobbe, in an article for the New York Herald titled “Painters of Indian Life,” concluded that Remington had been the top man in his field.

Extremely interesting has been Mr. Remington’s development

from an illustrator into a painter. It has been slow, not because

of any lack of ability, but because there always was such a

demand for his illustrative work that he could not very well give

up or even relax from it sufficiently to devote the necessary time

to painting as distinguished from illustrating. But the pictures,

more than twenty in number, which he recently exhibited at the

Knoedler galleries showed him as a painter ….[5] (Figure 12)

Thus Remington had spanned two decades with his art, tailoring it along the way to suit his changing aspirations and developing self-image. Beginning as an academic realist and illustrator, he went on to experiment with color and produce nocturnal poems in paint. Then at the end of his life he explored Impressionism and landscape painting, ultimately closing his artistic career with an affinity for the Post-impressionist sensitivities of Symbolism. Seeing a Remington painting from 1889 hung next to one of 1909, one might ask how the same hand could have produced both works. In this volume that question is answered, revealing the evolution of Remington’s unique creative genius.

The essay “That Hymn of Divine Crudeness?”: Frederic Remington The Painter” has been reprinted here with permission and in a revised form from an introductory essay of the same title which appeared in Frederic Remington. an exhibition catalogue published in 1991, by Gerald Peters Gallery, Sante Fe, New Mexico, in association with Mongerson-Wunderlich, Chicago. Illinois.

Endnotes

1. San Francisco News Letter (January 8, 1910), p. 3.

2. Samuel Isham, The History of American Painting (1905; rpt. New York: The MacMillan Company, 1936), p. 501.

3. Quoted in Allen P. Splere and Marilyn D. Splete. Frederic Remington—Selected Letters (New York: Abbeyville Press, 1988), p. 291. Original in the collection of the Owen D. Young Library, St. Lawrence University.

4. Perrington Maxwell, “Frederic Remington—Most Typical of American Artists,” Pearson’s Magazine, 18 (October 1907), p. 405.

5. Gustave Kobbe, “Painters of Indian Life,” New York Herald, December 26, 1909. Sunday Magazine Section, p. II.

Written By

Emily Wilson

Emily Wilson is the curatorial assistant at the Whitney Western Art Museum. She is a big fan of contemporary art and taxidermy. Living in the West has made her appreciate the region for its artistic and aesthetic draw.