John Mix Stanley: Artist as Entertainer

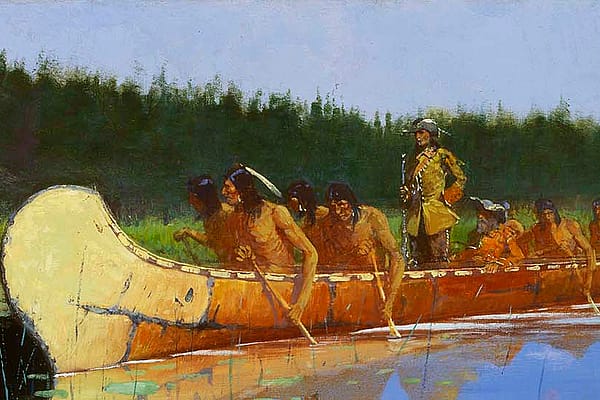

In the nineteenth century, many artists looked to market their art to the masses. The panorama (figure 1) offered artists a way to combine their art with a form of popular entertainment, thus capturing a wider audience and generating much-needed revenue.

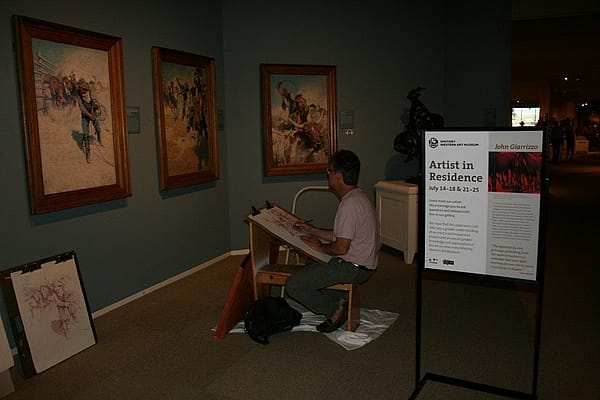

In 1853, Isaac Stevens hired John Mix Stanley to accompany him as his official artist on one of the government-sponsored surveys to map a route for the Pacific Railroad. Traveling from Saint Paul, Minnesota, to Puget Sound in Washington, Stanley logged more than a thousand miles working and sketching scenes of camp and Indian life, as well as the landscape along the way (figure 2). After his return from Washington Territory in 1853, Stanley settled in Washington, DC. One year later, he decided to take the sum of his experience from the Stevens’ expedition and channel it into a new artistic outlet: the panorama.

With the help of several artists and an author, Stanley created his first panorama, documenting and sensationalizing his time spent in the West, titled, Stanley’s Western Wilds. It consisted of forty-three scenes that loosely followed the timeline of the Stevens’ expedition. The panorama was exhibited in major East Coast cities such as Richmond, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York. This wide exposure helped Stanley gain commissions of his work.

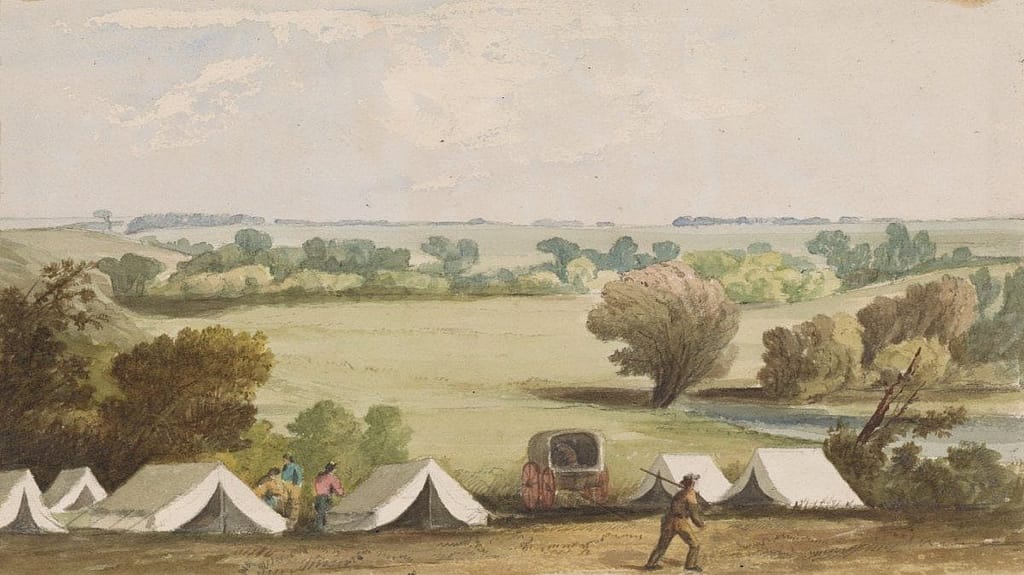

Patrons like Alexander Hamilton Redfield (figure 3) would request duplicate paintings from scenes he completed for his panorama for their private homes; Camp of the Red River Hunters, 1857, is one such work (figure 4). Although Stanley’s panorama has since been lost, it is because of these private commissions that we have some knowledge of its makeup.

Due in part to his first panorama’s great success, Stanley decided to create another panorama in tandem with artist Alban Jasper Conant (1821 – 1915). The second panorama, completed in 1862, contained seventy-seven scenes depicting events and battles from the first two years of the Civil War, entitled, Stanley and Conant’s Polemorama! Or, Gigantic Illustrations of the War. The word polemorama is a portmanteau, made from the words panorama and polemania, which meant rage for war. The second time around Stanley upped the spectacle, adding in musical selections that would play in tandem with the image and oratory. He traveled the work to Boston, Albany, and Detroit.

In both instances, Stanley’s panoramas brought both much needed income and attention to Stanley’s artistic work.

Written By

Emily Wilson

Emily Wilson is the curatorial assistant at the Whitney Western Art Museum. She is a big fan of contemporary art and taxidermy. Living in the West has made her appreciate the region for its artistic and aesthetic draw.