Spit Cleaning: Conservation’s Dirty Little Secret

Conservation is a very scientific field; we work in a laboratory for a reason. We make sure to observe proper safety precautions, and our labs are equipped with fume hoods, MSDS sheets, emergency eyewash stations, and protective gloves and eyewear. With a setup as careful as this, you would expect every treatment to involve dangerous and hardcore chemicals – and many do. Sometimes, though, the only thing an object needs is a little spit.

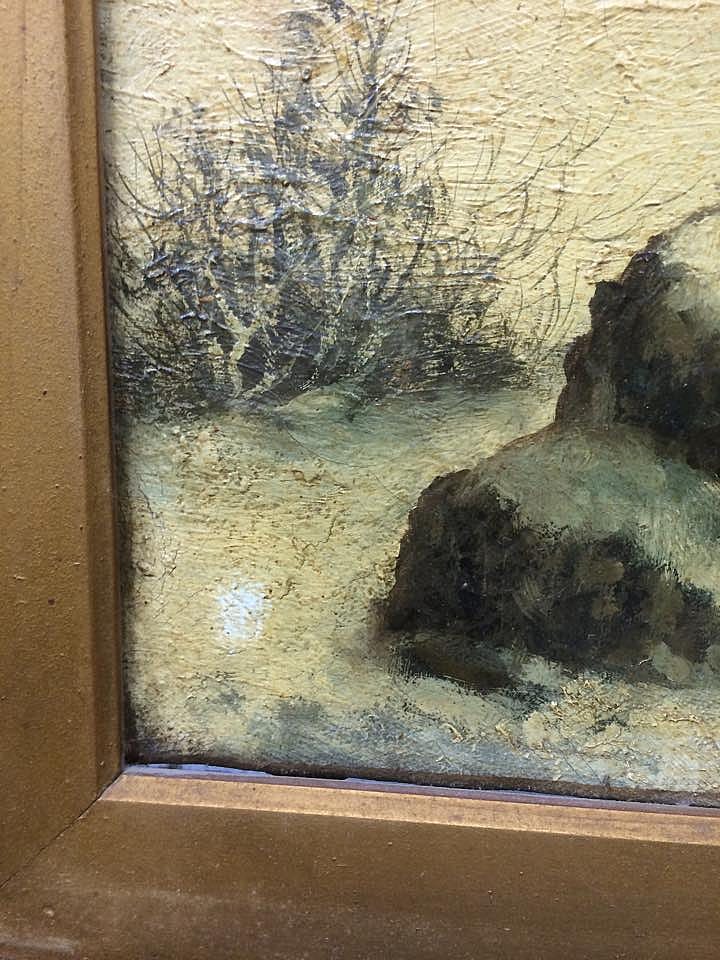

Spit cleaning isn’t just for shoeshiners. Documentation of spit cleaning as an art conservation technique goes back as far as the 18th century, and today it is used worldwide by conservators in a variety of specialties. We would never go so far as to lick or spit on a painting, but the method we use is remarkably simple. We make our own disposable swabs using cotton and wooden skewers, lightly moisten them, and roll them on the object we’re working on to remove dirt. The trick is to stay hydrated – dry mouth and double dipping are probably the biggest dangers that we run into with this technique.

So why is spit an effective cleaning solution? Human saliva contains the enzyme amylase, which is meant to break down food but also works well for breaking down dirt and grime on an object. It’s also a free and accessible resource, and it’s mild enough that we don’t need ventilation or any other safety precautions when we work with it. Right now in the lab at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, we’re working on a number of objects that will be spit cleaned as a part of their treatment. These include a painting by Henry Cross, a pair of gauntlets with Crow Indian beadwork, a leather and silver show saddle, and another leather saddle that used to belong to Buffalo Bill Cody. Despite the many virtues of spit cleaning, there will always be people outside of the conservation field who find it gross and disgusting. In treatment proposals, we sometimes refer to it as a “mild enzymatic solution” – no lies there, but it sounds a little bit more professional. Although it might seem simple, we wouldn’t generally recommend trying this method at home. You never know what kind of water-soluble materials might be lurking underneath the layers of grime on your object. If you want to have an artwork cleaned, it’s always best to consult a conservator first.

Written By

Allison Rosenthal

Allie Rosenthal is from Canton, Massachusetts, and recently graduated from Sarah Lawrence College with a degree in art history and chemistry. She is excited to be interning in the conservation lab at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West this summer, and hopes to pursue a career in book conservation.