Hummels: Not So Humble After All

Some of the objects we’ve treated in the conservation lab this summer have been pretty high-profile. In case I haven’t name-dropped Buffalo Bill enough yet, we’ve worked on both his saddle and his travel case. The California Mission saddle is all polished up and heading off on loan soon. And of course there’s the infamous Great Basin Winchester, which got a complete conservation treatment (including an x-ray at the local hospital) by our lovely supervisor Beverly Perkins.

One of my favorite things about conservation, though, is that an object doesn’t need to be famous or valuable to be worth our time. One philosophy of best practice for us in the field is known as the Rembrandt Rule: “Treat every object as if it were a Rembrandt.” And this makes sense, right? My friend Perrine talked about this a little bit in her blog post “Functional Items as Museum Objects,” but when an item becomes part of a museum collection, it’s there for a reason. There is a significance to that item that makes it worth preserving. The same thing is true of an object that is privately commissioned for treatment—even if it’s something purely sentimental like an old family scrapbook, it is somebody’s treasure. It’s not our job to decide what makes something worth fixing, but it is our job to fix it.

Which brings me to the treatment I’m going to talk about today. My favorite project of the summer was not one of Buffalo Bill’s artifacts or an ornate saddle. At the beginning of August, I got to treat three privately-owned porcelain Hummel figurines. Hummels are collectible figurines based on the sketch art of Sister Maria Innocentia and manufactured throughout the twentieth century by the porcelain maker Franz Goebel. The Hummel figurines I was treating had fallen and broken into several pieces, and the owner wanted them put back together again.

The first step of my treatment was a little bit of scientific analysis. I wanted to see if the Hummels were all made of the same material. This was more out of curiosity than anything else—I could have begun without this information, but it was helpful to know that my treatment would have the same effect on each figurine. I used x-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis to test a flesh-toned area of each Hummel. (For more information on XRF, see Perrine’s blog “Elemental My Dear Proctor.”) The elemental makeup of each test spot was very similar, and I was able to conclude that all three were made of the same or similar porcelain material.

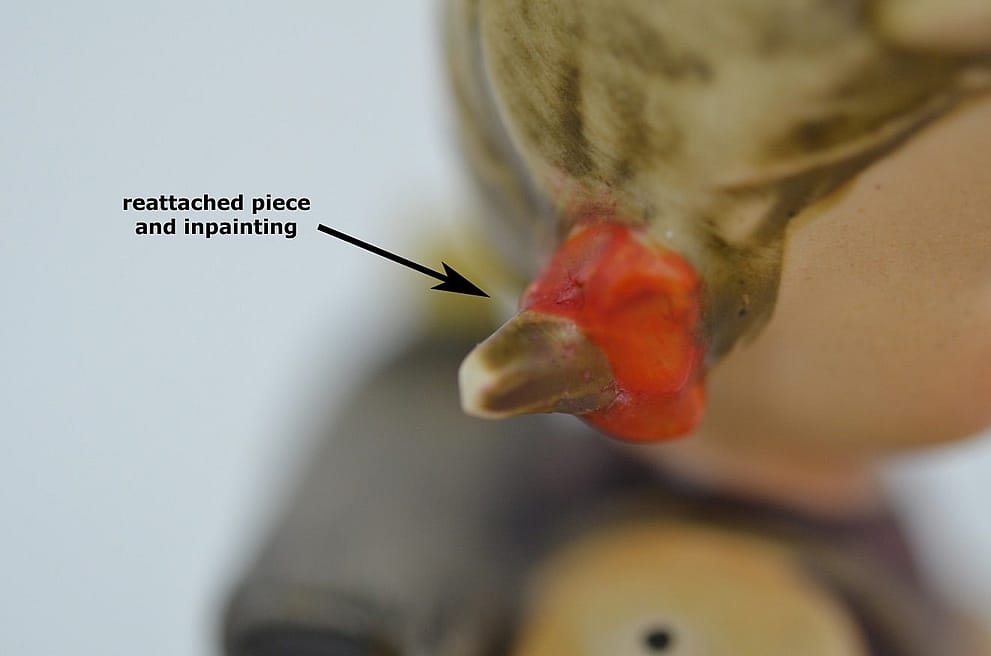

I used the adhesive Paraloid B-72 in a 1:1:1 solution of ethanol and acetone to reattach the broken pieces. B-72 is great because it’s strong yet reversible; if anyone ever needs to undo my repairs, the adhesive is soluble in both ethanol and acetone.

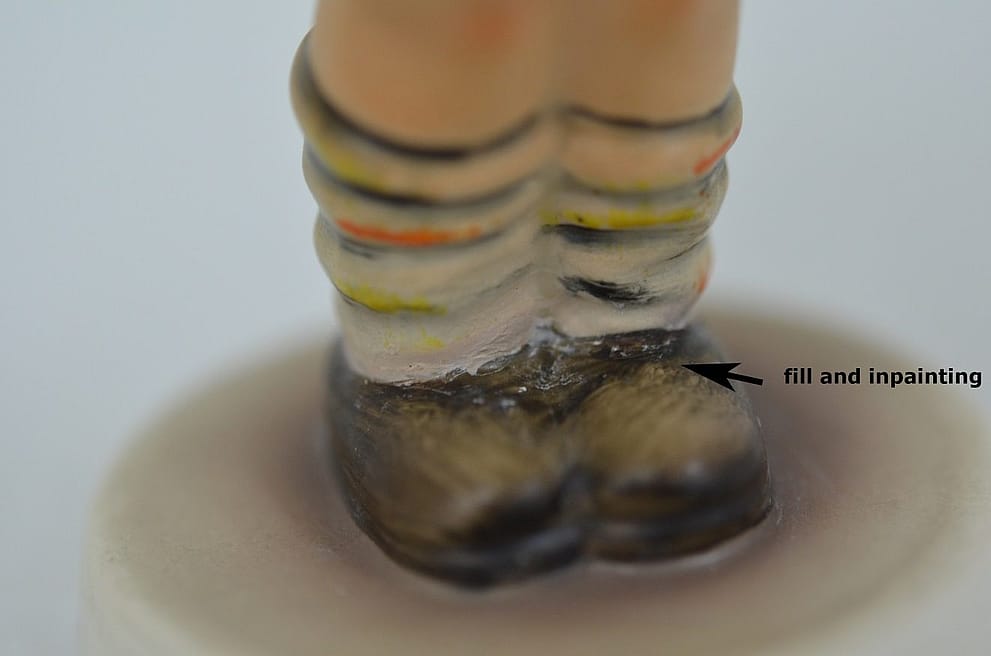

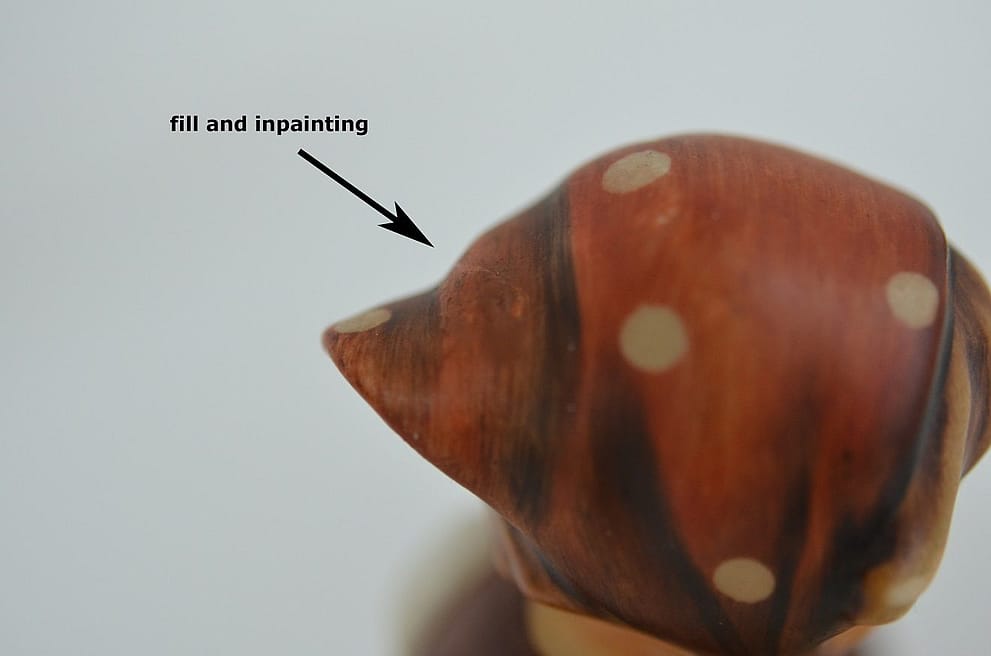

Although the pieces were firmly stuck together at this point, some losses remained along the cracks and in various areas on the surface of the porcelain. I filled the losses with Modostuc, a commercially-available filler paste made of polyvinyl acetate and calcium carbonate.

Then came the best part: inpainting. I used Liquitex acrylic paints to inpaint my fills so that they blended in with the rest of each Hummel.

So why was this my favorite treatment of the summer? Besides the fact that the inpainting was really, really, really fun to do, I like that these Hummels are meaningful enough to somebody that they wanted them fixed. It’s easy to see the merit of conserving a showstopper museum object, but in this field a family heirloom is equally worthwhile and I appreciate that a lot. These might not be Buffalo Bill Cody’s Hummels, but they sure are important to someone, and it was nice to play a part in their story.

Written By

Allison Rosenthal

Allie Rosenthal is from Canton, Massachusetts, and recently graduated from Sarah Lawrence College with a degree in art history and chemistry. She is excited to be interning in the conservation lab at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West this summer, and hopes to pursue a career in book conservation.