The Art of John Mix Stanley – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West in Spring 2015

Painted Journeys: The Art of John Mix Stanley — Revealing an unknown artist

By Mindy N. Besaw

John Mix Stanley (1814–1872) was a major figure in nineteenth-century American Art, yet his life and art remain unexplored. He was an ardent adventurer who traveled to the West more than any other artist of his time. He was a painter of American Indians and was sensitive to their changing circumstances during a tumultuous time in our country’s history.

Throughout his travels and in his depictions of American Indians and western scenes, Stanley remained dedicated to fine art, not just documentation. Stanley’s imagery played an important role in creating the legacy of the American West and in shaping our American identity. Yet, even for enthusiasts of American art and the West, Stanley is relatively unknown. The special exhibition Painted Journeys: The Art of John Mix Stanley, reveals this little-known artist and highlights how Stanley is relevant and important today.

Indian Gallery

Stanley shared the western art limelight during the mid-nineteenth century with George Catlin (1796–1872), Alfred Jacob Miller (1810–1874), and William T. Ranney (1813–1857)—all of whom have enjoyed important exhibitions and scholarship in recent years. Like Catlin, who first journeyed up the Missouri River in the 1830s to paint the Plains Indians and their way of life, Stanley explored the West in search of American Indian and frontier themes on an expansive scale.

From his travels in the 1840s and 1850s, Stanley assembled a vast collection of Indian portraits and scenes of daily life, which became the heart of his famous Indian Gallery of more than one-hundred-fifty paintings. Stanley lobbied the United States government to purchase his Indian Gallery on several occasions, but each time he was disappointed. Then, almost all of the collection was tragically destroyed in an 1865 fire at the Smithsonian, where it had been on exhibit.

Despite this great loss, we can still learn much about Stanley’s unique approach to American Indian subjects from his existing portraits and paintings of Indian life. During his travels, Stanley witnessed the pressures on American Indian peoples to adapt or perish in the wake of the 1830 Indian Removal Act. The legislation forced the migration of southeastern tribes to west of the Mississippi, and thereby, increased incursions from trappers and settlers into the West. As obstacles in western settlement, many stereotyped American Indians as war-like savages. Stanley generally avoided these negative stereotypes and regarded American Indians as worthy subjects for fine art.

Stanley’s scenes of Indian life often feature family groups and quiet moments. In Group of Piegan Indians, men dressed in their finest apparel rest on an outcropping to smoke. Stanley presents the act of leisure smoking as a special activity that afforded men a universal bond, relatable to Stanley’s audiences across cultural boundaries. These intimate and approachable scenes celebrate renewal and regeneration. Yet at the same time, Stanley also lamented the doomed race with his powerful painting, The Last of Their Race.

In this allegorical painting representing different tribes, the family of many generations stands at the westernmost part of the continent. The waves of the Pacific Ocean lap at their feet, and the sun sets in the distance.

Capturing the character of America

Indeed, Stanley does stand out as a painter of American Indians. However, this exhibition also includes his western genre paintings, history paintings, landscapes, scenes from exploration, and portraits—all to demonstrate the breadth and quality of his career. As a vital narrative painter, Stanley’s works and artistic vision contributed to shaping the American identity.

The American character was a prominent theme for Stanley, just as it was for his contemporary, William Ranney. While Ranney focused more on trappers and pioneers in his western pictures, Stanley painted images from multiple perspectives. He wrestled with contradictions in the American character—as a champion of Manifest Destiny and the pioneer ethos on one hand, and a defender of Native American culture and tradition on the other. Stanley reconciled these disparate images of the West as natural paradise or theater of progress by painting visions of Native America alongside one of an expanding European-American component. He was able to bridge both worlds and resolved the tension by idealizing—but not privileging—its divergent elements.

Stanley’s Indian Gallery was a major statement of the artist’s support for American Indians, but he also painted burgeoning towns in the West. For example, Stanley painted Oregon City on the Willamette River following two trips to the area in the late 1840s to sketch local Indians and scenery. This painting, completed a decade later, is a complex metaphor for the changes on the frontier. An Indian couple is present in the foreground of the painting, cast in the shadow and looking somewhat dejected—they are not part of the scene of progress reflected in the burgeoning community behind them. The sunny town speaks to the alternate vision, reflecting Euro-American aspirations of development and expansion. Oregon City was the terminus of the Oregon Trail and the dream destination for many pioneers in the mid-nineteenth century.

Exploring and sketching and painting

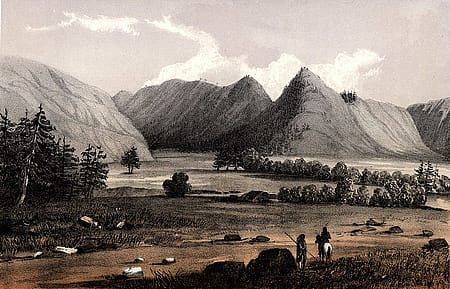

Stanley’s ambitious exhibition program, and his formidable exposure through vital government reports on western exploration, gave him a broad platform for expression afforded few other artists of his day. Stanley’s images of the Southwest reached another

audience when published in Major William H. Emory’s Notes of a Military Reconnaissance from the journey through the territory with General Stephen W. Kearny in 1846.

Following his work on the Isaac I. Stevens 1853 expedition searching for a northern route of the transcontinental railroad, massive reports from the railroad surveys further disseminated Stanley’s images. Publishers based these final prints on Stanley’s field sketches, and then watercolors, completed a couple years after the expedition while Stanley was living in Washington, DC. In its broad reach, his imagery played an important role in creating the legacy and perception of the American West.

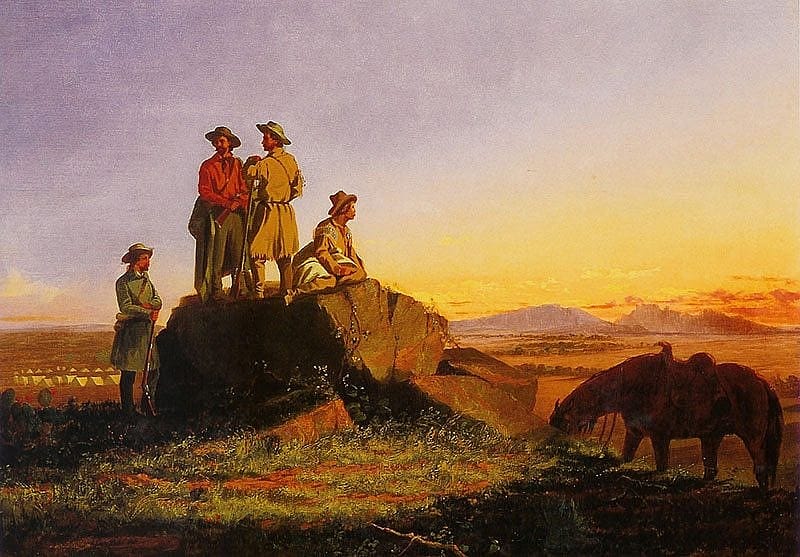

The Stevens expedition provided ample inspiration for Stanley’s artwork throughout the 1850s. Scouts along the Teton River, for example, pictures a group of the Stevens exploring party on a rocky outcropping against the Teton River Valley in northern Montana. The men, posed in a sturdy pyramid, are bathed in golden light and appear as masters over the surrounding landscape. A small, related painting, Untitled, Teton Valley Scene, shows the same composition as the larger painting, but is curiously reversed, with the tents to the right of the foreground rocks. This painting shows Stanley’s possible working process, as the figures are less resolved and Stanley’s under-drawing more evident.

Stanley also used his journeys and his art to convey images of the West to a popular audience with a huge moving panorama he titled Scenes and Incidents of Stanley’s Western Wilds. The panorama recounted his western adventures in forty giant images, which was for nineteenth-century audiences, akin to present-day movie theaters. Viewers delighted in the massive painted images while the narrator described the scene. Then, the panorama turned and a new image and corresponding adventure appeared. Although the panorama no longer survives, Stanley painted many smaller easel-sized pictures of the same scenes.

Obscure no longer

Throughout his career, Stanley constantly refined his painting style and skill. At a time in America when there was very little formal artistic instruction, Stanley sought out teachers. Moreover, when he aimed to make a living as an artist, he started as an itinerant painter, traveling through the Midwest and Northeast painting portraits of wealthy individuals. One of his early portraits, The Williamson Family, pictures the Manhattan merchant James Abeel Williamson with his wife and toddler son. Stanley’s depiction of the interior, furnishings, and figures is successful for the way in which the painting reveals the warmth and intimacy of the family, and the “sitters” prosperity.

Throughout the next thirty years, Stanley’s painting style, anatomy, and composition greatly matured, especially during the period of the 1850s in Washington, DC, where he was involved with the Washington Art Association. Compare, for example, the figures of The Williamson Family to the relaxed and varied poses in Group of Piegan Indians. At times in his career, he also offered painting instruction, contributing to arts instruction in America. Stanley constantly balanced his goals of conveying information—whether as an expeditionary artist or painting the likeness of his sitters in the Indian Gallery—while at the same time using sophisticated compositions and formal elements to emphasize artistic aspects of his work.

Stanley was remarkable in many ways—for the great distances he traveled (even before the transcontinental railroad was complete); for his determination in the midst of personal tragedy and loss of his Indian Gallery paintings; in his use of art as entertainment through the monumental panoramas; and for the sheer number of images that appeared in government expedition reports.

Stanley’s is a story of American history and art in the mid-nineteenth century, but it is also an artistic journey illustrating remarkable ingenuity. By investigating Stanley’s art and central insights in light of a complex time in American history, we can not only better understand that moment in time, but come to understand how Stanley has had a major part in how we perceive the American West. Stanley’s western landscapes and paintings of American Indian life afforded an eastern audience a view into an unfamiliar part of their own country. The height of Stanley’s art and life also pre-dates many of the artists we now associate with the West. Thomas Moran, for example, had not yet completed his monumental painting of Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone when Stanley died in 1872, and Yellowstone had only been designated a national park for a month.

Painted Journeys: The Art of John Mix Stanley is a major contribution to the study of nineteenth-century American Art in its revival of Stanley’s art and career. The exhibition examines Stanley’s unique approach to Native American scenes and explores the shaping of nineteenth-century American identity through visual images of the West. Painted Journeys is on display at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West June 6 – August 29, 2015; at the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma, October 3, 2015 – January 3, 2016; and at the Tacoma Art Museum in Tacoma, Washington, January 30 – May 1, 2016.

Mindy N. Besaw is the former Margaret and Dick Scarlett Curator of Western American Art, Whitney Western Art Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. She is now Curator for the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, a position she began November 19, 2014. She is co-curator of Painted Journeys along with the Center’s Director Emeritus and Senior Scholar, Peter Hassrick.

John Mix Stanley, a timeline

- January 17, 1814: Born, Canandaigua, New York.

- 1828 – 1832: Apprenticed as a wagon maker, and works as a house and sign painter.

- 1834: Turns to portrait painting for a career, and for the next several years, travels through the Old Northwest (Michigan, Wisconsin, and Illinois), and New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Troy, New York, as an itinerant painter.

- 1842: Travels to Fort Gibson, Oklahoma, to paint American Indian portraits.

- 1843: Attends three Indian peace councils in the Republic of Texas and the Oklahoma Territory.

- 1846: First exhibition, Stanley’s American Indians, opens in Cincinnati, Ohio.

- 1846: Travels by caravan on the Santa Fe Trail from Westport Landing, Missouri, to Santa Fe, New Mexico. There he becomes a topographical draughtsman on a military expedition to occupy the northern provinces of Mexico with Stephen Watts Kearny and surveyor William H. Emory. (Kit Carson served as a guide for much of the expedition.)

- 1847: Travels through the Northwest and arrives in Oregon City to paint American Indians who lived in the region; continues farther north into present-day Washington State where he narrowly misses the Cayuse massacre at Wailetpu Mission.

- 1848: Travels to Honolulu, Hawaii, to paint portraits of the King and Queen of Hawaii.

- 1850 – 1852: Exhibits his North American Indian Portrait Gallery throughout New York, Connecticut, and Massachusetts, depositing the gallery of paintings at the Smithsonian Institution in 1852.

- 1853: Isaac I. Stevens, survey leader, hires Stanley as an artist on a project to determine the northern route for the Pacific Railway from Saint Paul, Minnesota, to Puget Sound, Washington.

- 1854: Marries Alice Caroline English, a young schoolteacher with whom he has five children. Stays in Washington, DC, for the next nine years while he actively exhibits his artwork and is involved with the Washington Art Association.

- 1863: Moves to Buffalo, New York, and later to Detroit, Michigan.

- 1865: Stanley’’ Indian Gallery is destroyed in a fire at the Smithsonian Institution; only seven paintings survive.

- 1868: Travels to Germany to get estimates on chromolithography; transforms seven paintings into chromolithograph prints over the next three years.

- April 10, 1872: Stanley suffers a heart attack after an illness of several months, and dies at age 58. His wife survived him, until her death in 1891.

Post 100

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.