The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act: What Was at Stake?

This is an introduction to a series of posts about the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) and how the act works within the museum world. First, I delve into the historical background. What events led to the creation of the NAGPRA law?

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990—a federal law passed by Congress—gave Native American tribes legal power to reclaim tribal ancestors (human remains) and their associated funerary items and a variety of newly categorized objects from museums. The relevant objects were listed as: unassociated funerary items, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony. (There will be further explanation of these objects under the law in my next post.) No longer would attempts at legal repatriation have to rely on a case-by-case basis. There was now a law that recognized the human, religious, and property rights of Native Americans while ending “a pattern of one-way transfers of objects from Indian hands to non-Indian institutions” (Meister 1996). The existence of the NAGPRA law allowed for tribal collaboration with museum staff in the form of consultations and an atmosphere of respect for indigenous voices that was rarely given before. So, how did these collections accumulate in museums?

Human remains and objects had been raided and stolen, tribal objects were given away under duress, and both human remains and objects were taken with scientific justification to salvage a representative collection of what anthropologists thought were disappearing cultures. The “salvage anthropology” school of thought occurred as Native Americans were pushed onto reservations in the late 1800s. Anthropologists wanted the pre-contact material of these tribes, which to them was especially relevant in the time of westward expansion, assimilation, and further culture loss. The scientific community felt that museums were ways to display material culture for visitors in a time before television and the internet. Museums would care for these objects in ways they felt that tribes could not (or would not). They mistakenly doubted the continued viability of tribal communities in their current form.

Native American grave sites were raided in order to perform craniology and phrenology. These popular 19th-century pseudo-sciences were used to correlate human measurements with racial and psychological traits. These skull measurement results became a way to scientifically justify racism. To make matters even worse, the remains were not returned. The Federal Antiquities Act of 1906 at first seemed to be a decent legal guard against widespread looting for archaeological sites on federal and tribal lands. Instead, it neutralized the individuality of Native Americans buried there. They became “archaeological resources to be studied, not individuals with the right to remain respectfully buried” (Wilbert 2012). This ruling “solved” the problem of looting by classifying looting as something non-scientists did while moving Native Americans into a scientific realm to be analyzed. The law, in effect, only changed the status of those doing the digging.

After Native Americans overcame threats of tribal termination and further loss of land, they joined other groups speaking back to power in the 1960s and 1970s and questioning the legality of North American ethnographic collections. There were a few attempts at repatriation in the 1970s and 1980s, and tribes learned to focus on requesting the return of specific items (with a detailed explanation of the item’s significance) instead of making a blanket request for “all sacred objects” within a museum. In 1989, the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) Act passed and established the NMAI as the newest museum of the Smithsonian Institution. It also required the Smithsonian to produce an inventory of human remains and funerary objects that would be returned upon a federally recognized tribal request.

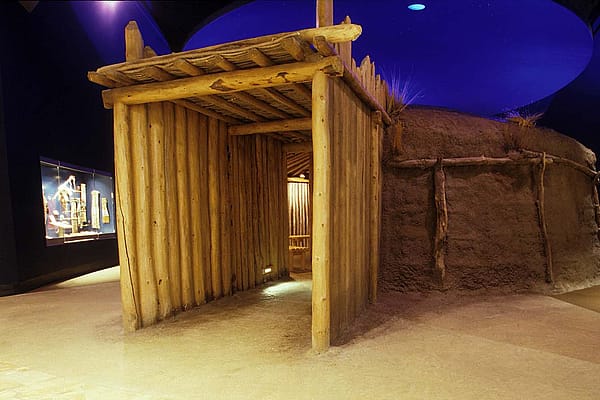

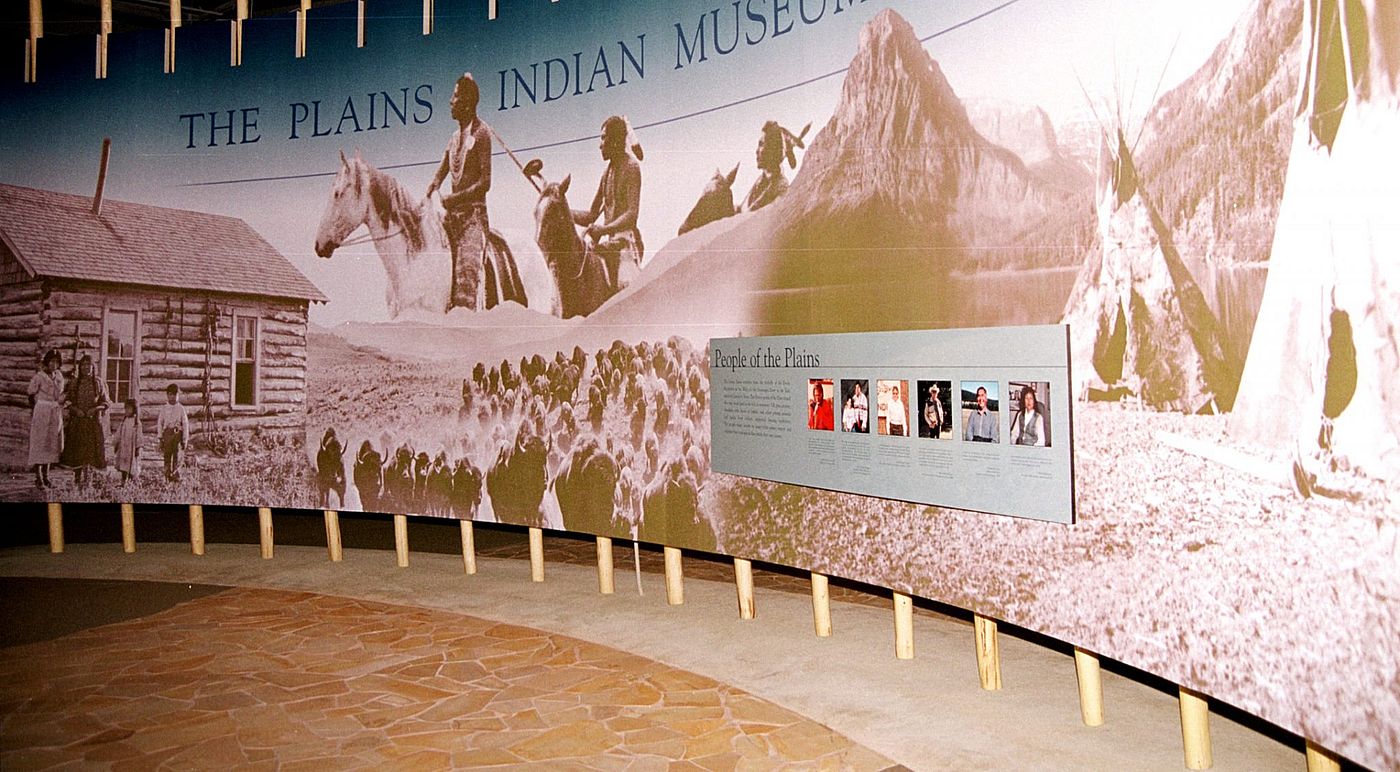

In 1976, the Plains Indian Museum Advisory Board was formed, and the Plains Indian Museum gallery opened at the Center of the West in 1979. The Board developed a Sacred Materials Policy, which preceded NAGPRA and identified a cooperative relationship with Native Americans: “Underlying this…is the Museum’s interest in caring for and interpreting its collection in a respectful manner according to the cultural traditions and religions of Native American people.” It was not difficult to foresee how a national law could be informed by the language of the NMAI Act and other institutions.

Next Time: Breaking down the law’s sections

*For further information: Meister, Barbara. Mending the Circle: A Repatriation Guide. American Indian Ritual Object Repatriation Foundation, New York, 1996.