Addie Sharp – Points West Online

Originally featured in Points West magazine in Summer 1998

Addie Sharp: A Forgotten Figure of the Turn-of-the-Century West

By Marie Watkins, Guest Author

Editor’s Note: Research for the article was done in the McCracken Research Library, using the scrapbooks and other resources in the Joseph Henry Sharp archives, a gift of Mr. and Mrs. Forrest Fenn. Watkins was doing research for her dissertation, “Painting the American Indian: Joseph Henry Sharp and the Poetics and Politics of American Anthropology.”

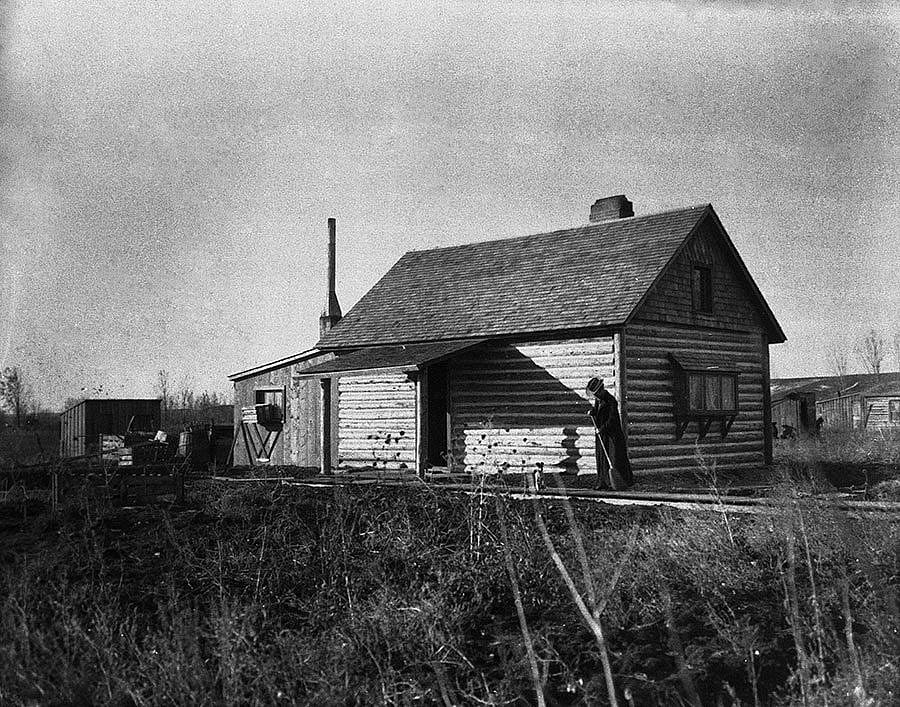

A refined Midwesterner, Addie Byram Sharp (1863–1913) “roughed it” with her husband, Joseph Henry Sharp (1859–1953), one of the foremost painters of the American Indian, “in the Wild West” at the turn of the century. Her travels to various Indian reservations paralleled those of her friend, Alice Fletcher (1828–1923), a pioneering anthropologist, reformer, and feminist. Addie Sharp, like Fletcher, turned her observations into public lectures on the Indian cultures she encountered. She often used her husband’s paintings as visual props and illustrations. The literature on Sharp, however, has ignored this aspect of Addie Sharp’s public life, preferring to depict her as a supporting and dutiful wife, submerged in the demands of patriarchal culture.

From clippings she collected for the scrapbook recounting her husband’s career, Addie Sharp included pieces of her life she deemed equally important and proclaimed that she not only contributed to her husband’s career, but had projects of her own. Placed next to news clippings of Sharp’s paintings were letters of reference and news articles that promoted and reviewed her lectures. Well-received among women’s clubs and museum gatherings of middle-class audiences, who were typically interested in intellectual topics, Addie Sharp awakened considerable interest in Native Americans. Regarding her talks as educational, the newspapers encouraged children to attend.

Addie Sharp’s winter lectures from 1900 – 1901 included the topics “Notes on Indian Life” and “Experiences Among the Indians” and coincided with Fletcher’s public lectures on Native American cultures in Cincinnati. Critics provided credentials of authenticity for Addie Sharp as an authority on Indian life and lore as they did for Sharp as a painter of the “real Indian.” By virtue of “so many summers in the land of the red man” among “the Pueblos at Taos…and on the reservations and at the home of the Crows and Siouxs (sic) in the Dakotas and Montana,” a newspaper vested her lecture with knowledge and expertise. With affirmation of her “original research” in the papers Addie Sharp took on the semblance of an anthropologist in the field “as she made interesting notes of the characteristics of the Indians and has gathered much charming ‘folklore’ related to her by Indian chiefs and the women and children.” The reporter further credited her as “an intelligent observer with a mind trained along these lines by extensive travel and many years residence among different peoples.”

Audiences found Addie Sharp and her lectures fascinating for her intimate “glimpses of the far West.” Surrounded by her legitimizing “immense and priceless” collection of Indian artifacts and crafts and her husband’s sanctioned Indian paintings on three walls, Addie Sharp “spoke of the humor, pathos and sentiment as seen by sympathetic eyes.” She informed the audience “of superstitions, in some cases parallel to our own, gave personal experiences, a dip into ethnology, descriptions of scenery and dances, etiquette of the tepee, told the story of Little Wolf, the art of this people and their religion.” One critic called “her story of the Indian Cinderella” a hit among the audiences and thought the “legend of ‘Ojo Calente,’ or ‘Hot Springs of New Mexico’ closed out a most delightful evening.” She championed the American Indian by pointing out shared characteristics with white Americans, yet she needed the American Indian to be different in order to be authentic and thus of interest to her public. Her relationship with Native Americans was a contradictory one, as was her husband’s.

The newspapers also thought Addie Sharp filled “with the art spirit, as well as her husband,” and that she contributed significantly to Sharp’s success as a painter. She frequently acted as spokesperson and interpreter for the couple, as Sharp was deaf. At the turn of the century, Addie Sharp’s perceived feminine characteristic of intuition, as well as her grace and charm, impressed both reporters and her audience.

Her contemporaries also saw her as a “progressive” woman, like the female anthropologists of her day. They remarked on her stamina and endurance in the zero degree winter temperatures in the West. Like her husband, Addie Sharp promoted and encouraged their image of rugged western individualism, which connoted authenticity to her eastern readers. Excerpts from her letters back home found their way into the local papers. They told of the Sharp’s life, which was lacking in eastern comforts and niceties, but enriched by anecdotes of western characters and colorful encounters. “We are in love with the West,” she made perfectly clear. “It is full of human nature and thoroughly American, and the older I grow the more I care for poor, old human nature. It is so real. For a long time I wondered where the real was. We had it in our art, but not among people. Out here we find it unadulterated.”

Through her lectures and letters, the urban public encountered information about exotic rituals and authentic Indian crafts and relics. Deriving prestige from her life among the Indians, Addie Sharp educated her audiences on Native American culture. However, from the news articles’ descriptions of her lectures, she saw American Indians with a romanticist and primitivist vision that did not include contemporary socio-political problems on the reservations. Although her lectures depicted American Indians in terms of the familiar, that is, similarities between white and Indian cultures, Addie Sharp, like many others of her generation, also constructed an ethnic identity of the American Indian as a primitive figure, conveying difference.

Post 132

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.