The Arts and Culture of the Ute Indians – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2002

Mountain-Family-Spirit: The Arts and Culture of the Ute Indians

By Emma I. Hansen

Curator Emerita, Plains Indian Museum

We don’t have a migration myth because we have always been here.

—Eastern Ute elder [1]

From time immemorial the Eastern Ute people of present day Colorado and Utah have considered the Rocky Mountains their traditional homelands. The Ute origin story and tribal memory recognize this region—stretching north and south through central and western Colorado and into Utah and northern New Mexico—as the place where their tribal identify and most important elements of cultural life were formed.

The Utes are intimately connected to the mountains and the surrounding area as both the physical and spiritual center of their existence. According to tribal traditions, Sinaway, the Creator, provided this sacred land for the Ute people although his helper Coyote foolishly scattered people from other tribes who spoke different languages in surrounding areas. Their environment shaped the Ute people as they developed creative ways of exploiting its diverse altitudes, ranges, plants and animals on a seasonal basis. Over time the Utes have also served as spiritual caretakers of the land and its resources according to a belief system of cultural values, ideals, and ceremonies that delineated their roles as hunters and plant gatherers in this mountainous region.

Mountain-Family-Spirit: The Arts and Culture of the Ute Indians, an exhibition that appeared at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in 2002, was the first national touring exhibition focusing on the Eastern Ute people. It was assembled by the Taylor Museum of the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center with added material from the Center. The exhibition title embodied the most important elements of Ute life—the mountains in which they originated and lived, the family in which individuals are born and work together to build their lives, and the spirit that connects the Ute to their land and to each other. The exhibition explores these themes in relation to the history of the Ute bands and tribes through the interpretation of many rare and important collection objects from major North American museums.

The Ute call themselves Nuche meaning “mountain people.” They call their language Nuu-a-pagia. The word “Ute” is apparently a corruption of the Spanish word Yutas, which is possibly derived from the term Guaputu. According to Spanish documents, people of Jemez Pueblo identified the Utes as Guaputu a term that refers to people who live in shelters covered with straw—a likely description of the domed shaped brush lodges in which the Ute lived. Today, the Eastern Ute live on three reservations in Colorado and Utah: the Southern Ute tribe with headquarters at Ignacio, Colorado; the Ute Mountain Ute tribe with headquarters at Towaoc, Colorado, and the Northern Ute tribe on the Uintah and Ouray reservation, with headquarters at Fort Duchesne, Utah.

In addition to the mountain environment, other factors contributed to the development of the distinctive Ute culture including their shared cultural heritage with Western Ute people of the Great Basin and their geographic location with Navajo, Apache, and Anasazi or Rio Grande Pueblos to the southwest, the Plains tribes to the east, and the Shoshone to the north and west. They were also later influenced by the arrival of the Spaniards who established colonies in the southwest in the 16th century and Anglo-Americans who achieved political dominance in the region in the mid-19th century.

Although there are linguistic and historical differences between the Eastern Ute and the Western Ute, a Great Basin people living in present day central and Western Utah, there are also many similarities. As hunters and plant gatherers, Eastern Ute people followed a seasonal round of economic activities during which they traveled into the mountains, east into the Plains, and to the Colorado Plateau west of the Rocky Mountains. The land and resources of the Colorado Plateau were similar to that of the Great Basin region inhabited by their Western Ute relatives.

Ute lodges built of brush over a domed framework of poles are reminiscent of the homes of Western Ute people. The lodges were practical in terms of the frequent movements of the Ute as they traveled through diverse regions in search of game and plant resources. Ute families and small groups sometimes moved over several hundred square miles as they traveled from north to south and east to west as well as from the mountains in the summer to the lower lands of the valleys and plains in the winter.

As Ute families moved throughout these environments, they became aware of changes in resources that might occur from year to year. Their survival depended upon noticing factors that indicated abundance or dwindling of particular plant foods or game and planning the timing and destination of their next move. Anthropologist James A. Goss has characterized Ute knowledge of their environment in the following way: “If you stop and think about it, they were excellent ecologists because it wasn’t just academic to them, it was important to their survival to know their environment.” [2]

Ceremonial life closely followed the economic seasonal round of activities. The Bear Dance (also known as the “woman-step dance”) is a spring renewal ceremony still performed today that emphasizes the relationship of the Ute people to the mountains and the bears as the guardians of the mountain resources. It took place in early spring when groups came together to visit and make alliances and courtship took place between young men and women. During this time, people who did not survive the winter were commemorated.

Many of the plant foods used by Eastern Utes were similar to those available to their Western relatives—pine nuts, acorns, and small seeds collected in the Colorado Plateau and processed through roasting or parching over hot coals and either stored for later use or ground into a flour that could be used for mushes or stews; berries, including chokecherries, buffalo berries, service berries, elderberries, currants, and strawberries collected in the Rocky Mountains and Colorado Plateau; and, roots collected in the spring using a digging stick and eaten raw or dried for later use as food or medicines.

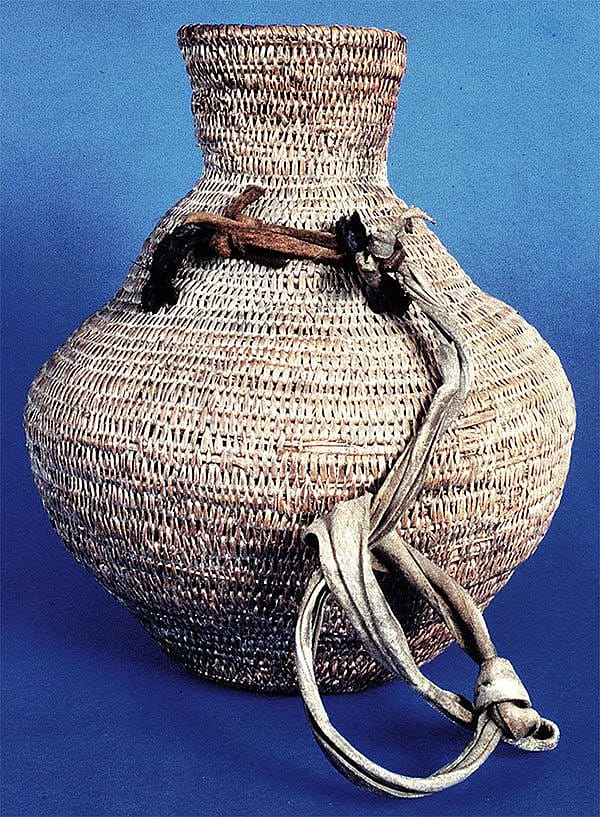

The tools used to process these foods also were similar to that of the Western Ute—basketry made for collection of berries and other foods, winnowing trays, and water jugs lined with pine pitch; spoons and ladles made from the horn of big horn sheep, wooden dishes and ladles, and pottery cooking vessels.

As mountain people, the Utes emphasize their heritage as hunters of large game including elk, big horn sheep, deer, and pronghorn. They also traveled to the Plains to hunt buffalo and, like the Western Ute, supplemented their food resources by hunting small mammals such as rabbits and squirrels. With the availability of horses from the Spanish colonies in the southwest through capture or trade by the early 1700s, the Utes became increasingly involved in buffalo hunting. Plains style hide (and, later, canvas) tipis, which were much easier to transport with horses, became more prevalent although people continued to build their brush lodges for summer use.

The Ute were also influenced by Plains traditions and artistic styles. In the late 1800s, the Utes adopted the Plains ceremony, the Sun Dance and, after a visit to the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Kiowa in Oklahoma in the 1890s, tribal members became involved with the Native American Church.

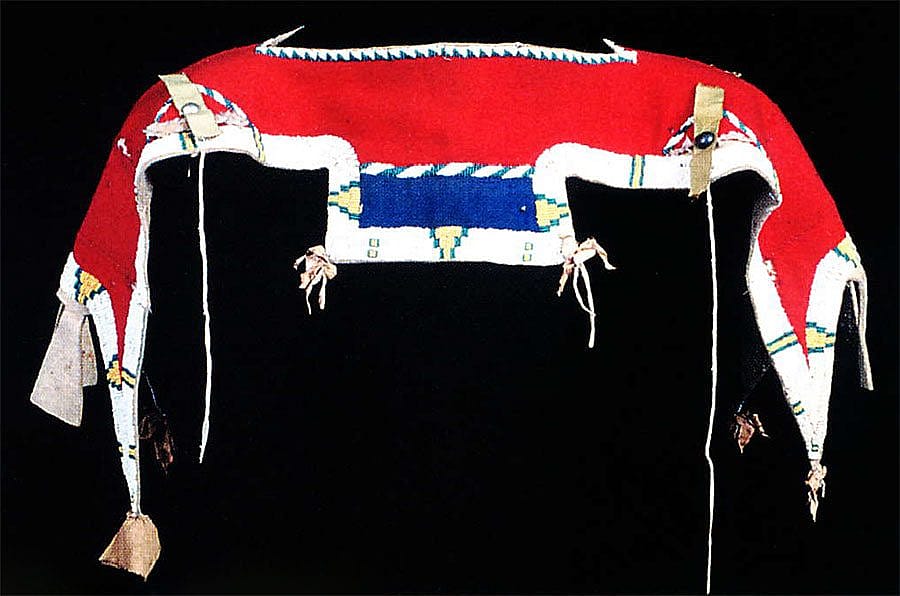

Their array of clothing included Southern Plains (Cheyenne and Arapaho) hide shirts, dresses, and leggings, Sioux-style dresses with fully beaded yokes, Cheyenne moccasins, and German silver hair plates and belt drops. As cloth became more readily available through trade, it was added to hide shirts, dress yokes, and other articles of clothing. The Utes added elements of the Southwest to this clothing including Navajo concho belts and sliver and turquoise bracelets and rings.

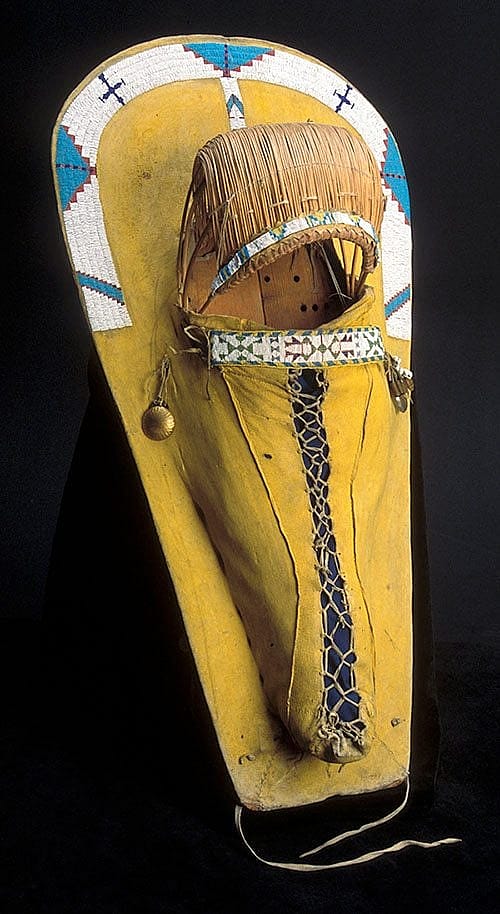

One tribally distinctive element of Ute material culture is the cradle, which provided a safe haven for babies when families traveled, and mothers and other female family members were involved in their daily activities. The cradles were made from cottonwood or pine boards covered with tanned hide. Sunshades, made of willow and wild cherry shoots, protected babies’ faces from the intense sun of the mountains and plains. Exquisitely painted in white or yellow pigments and decorated with beadwork and other ornaments, the cradle exemplified the importance of children and families to the Ute people.

Beginning in 1859 with a series of public campaigns to remove the Utes from their homelands and resultant treaties and land cessions, the Utes lost the greater part of their lands. The slogan in newspapers and posters was “The Utes Must Go!” for the miners, cattlemen, and politicians who wanted Ute homelands. By 1895 with the assignment of individual allotments and opening of remaining lands to settlers, the Utes were left with small reservations in southwest Colorado and Eastern Utah.

Prior to the arrival of Euro-Americans the Utes learned how to survive the harsh conditions of their mountain environment. Similarly, Ute people have survived the losses of their lands and concurrent threats to their culture. This survival is embodied in the enduring tribal ceremonies and traditional and innovative arts – the songs and dances, beautiful clothing, cradles, baskets, pottery, and paintings, that remind Ute people today of their shared cultural heritage and identity.

Notes:

1. Quoted in William Wroth, Ute Indian Arts and Culture From Prehistory to the New Millennium. (Colorado Springs: Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, 2000), p. 53.

2. James A. Goss, “Traditional Cosmology, Ecology and Language of the Ute Indians,” Ute Indian Arts and Culture From Prehistory to the New Millennium, p. 34.

Post 134

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.