Remington Among the Ute Indians – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2002

Remington Among the Ute Indians

By Peter H. Hassrick, Director Emeritus and Senior Scholar

Frederic Remington was nothing if not peripatetic and especially that was true in his life-long romance with the American West. From his late teens, Remington relished opportunities to travel to the frontier. Later, as an artist and illustrator, he sought first-hand connection with his muse by visiting the West numerous times each year, often for several weeks at a stint. One trip, however, a swing through Colorado in 1900 where he enjoyed a stop-over among the Ute Indians near the town of Ignacio, proved to be especially significant for the artist. His sojourn among the Utes represented not just his usual quest for pictorial inspiration and story material (although he collected both). It was a journey of self-discovery, one that proved transformative and revelatory in its result.

In the late autumn of 1900 Remington negotiated with Shadrach K. Hooper, the general passenger agent for the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad, for a free ticket from Denver to Santa Fe. Remington had never been to Colorado before, was unacquainted with its magnificent scenery, its spectacular ranches and its native people. He was searching for fresh material for stories he wished to write and illustrate but more than that, he wished for a chance to walk some novel ground.

Remington granted an interview with the Denver Republican two days after he arrived at the foot of the Rocky Mountains. He told the paper’s reporter that the West contained a myriad objects for the artist and that he was there to explore some new ones. Among those subjects he mentioned were the Utes of Southern Colorado. Utes, he commented, “are Indians with whom I am not at all familiar. I am going to study them.” He concluded his interview with a prophetic remark, “My present trip is sort of a finishing touch to my Western education…”

Remington departed Denver on October 22 and traveled by rail west to Grand Junction and then south to Silverton and Ouray. From the latter town he wrote home to his wife that he had enjoyed, “magnificent scenery—particularly the Marshall Pass.” On the 26th of October Remington’s travels brought him to Durango. The Durango Democrat announced his arrival and noted that the artist’s celebrated reputation preceded him.

Mr. Frederic Remington the noted artist of world-wide fame arrived in Durango last night via Ouray and Silverton and will visit Ignacio today to study the Utes in their native not adopted home. Mr. Remington is possibly the best known of American artists through which his work on Harper’s Weekly and other illustrated publications. He is without a peer in his lines and he can rest assured of a pleasant and courteous visit to Ignacio, from agent, employees and Indians. This is really Mr. Remington’s first visit to Colorado and he finds much.

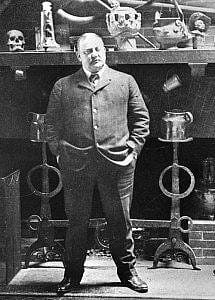

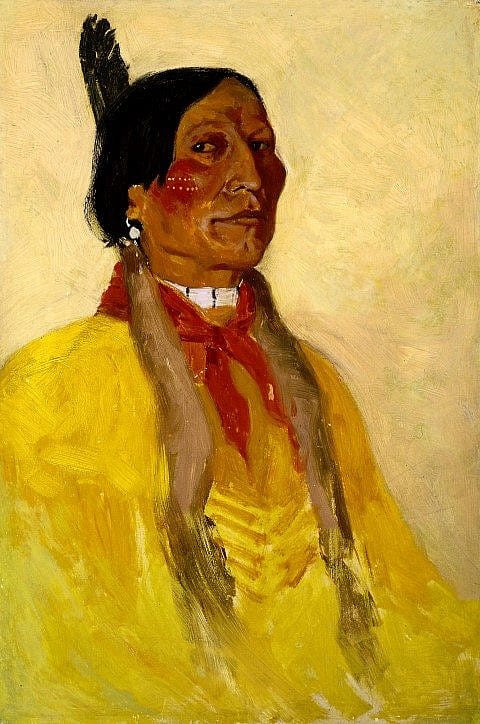

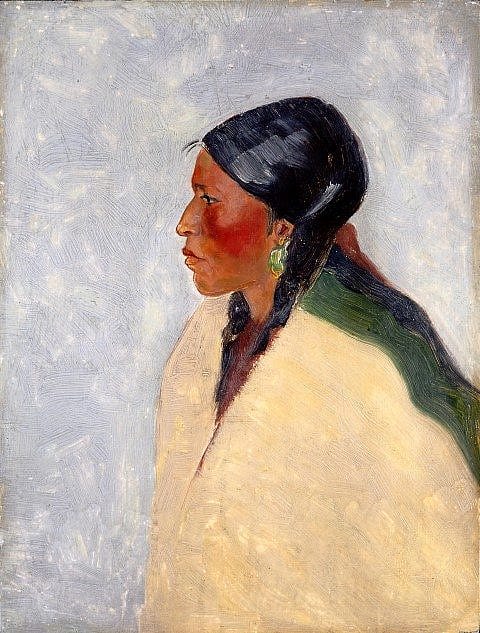

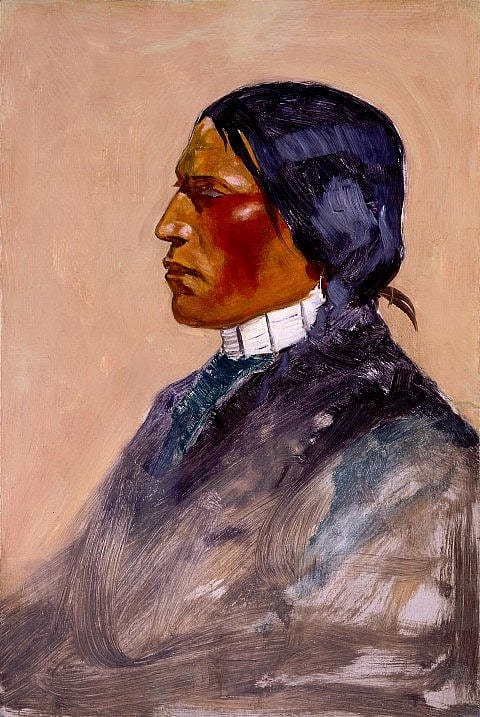

The next day, and for the nine subsequent days, Remington painted in and around Ignacio and the Southern Utes who called that region their home. It was cold there, and the sky hung heavy with snow clouds. Nonetheless, he painted about a dozen landscapes, three or four portraits, one of a chief, and purchased a number of artifacts for his prized studio collection, including what he called “1 Ute baby blanket very fine.” He shipped a crateload of Indian objects home, telling his wife, Eva, to keep an eye out for it as it was indisputably “the best stuff you ever saw.”

As inspiring as the Ignacio experience was for Remington, only one large, finished painting resulted. Titled A Monte Game at the Southern Ute Agency, the oil was illustrated with an extended cutline by Remington in Collier’s Weekly for April 20, 1901. Some of the figures were adapted from photographs Remington took and others resulted from painted studies he made at Ignacio. Remington described the scene with a hint of tongue-in-cheek moralizing.

As the Indian gather about the trader’s store at Ignacio, Colorado, some one of them before long spreads his blanket on the sand and begins to deal monte. He soon has patrons. A dozen or more games may be in progress, and they so not attract the interest of the outsider after three days. They are so open, so all in the sunlight, that one almost forgets that gambling is a vice. If an attempt were made to suppress the thing, the players would simply go over the first hill or into the first brush, neither of which is far. The Indian has always gambled, the Cuban has always fought chickens and various races have drank strong water through the ages. If all the military bodies of the earth, all the law-making bodies and all the police were to combine to stop one of theses things by force they could not do it. The moral is clear—if one wants to be a social reformer he shouldn’t begin by being a fool.

In a letter home to Eva dated November 4, 1900, Remington suggested that he had mixed emotions about his time at Ignacio. In one comment he says that “the Utes are too far on the road to civilization to be distinctive.” In another, he counters with the remark, “I am dead on to this color and trip will pay on that account alone.” Several conclusions could now be drawn. First of all, his artifact collecting suggests that his interest in Indian people resided in the past and not the present. Secondly, this feeling that the Utes were too settled to be interesting also confirms that his image of “Indian-ness” languished in history. He manifested only token interest in their real and present condition. And finally, his focus on landscapes and color studies indicates that what he really wanted to take home was a taste of Western light and topography onto which he could later paint scenes from his imagination rather than his experience.

On November 6, 1900, a day after leaving Ignacio, Remington wrote home again. His mood was one of disillusionment. “Shall never come west again. It is all brick buildings—derby hats and blue overhauls—it spoils my early illusions—and they are my capital.”

Following this trip, although he traveled West many more times in future years, he gradually abandoned his life as an illustrator and a recorder of contemporary Western life. More and more he turned to ideational pieces that romanticized a halcyon past for Indians and other people of the American frontier. Remington’s future journeys would be more cerebral than real. While he had been a pictorial witness to the Utes, they would be the last native peoples Remington would document.

Post 143

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.