The Legacy of the Buffalo, in Legislation and in Bronze

On May 9, 2016, the American bison (or, buffalo) was named the first national mammal of the United States of America. This recognition underscores the significant strides made by the species, which faced extinction in the early twentieth century. The Whitney Western Art Museum recently acquired a work of art that played a part in the story of the newly designated national mammal — Alexander Phimister Proctor’s sculpture, “Q Street Buffalo.”

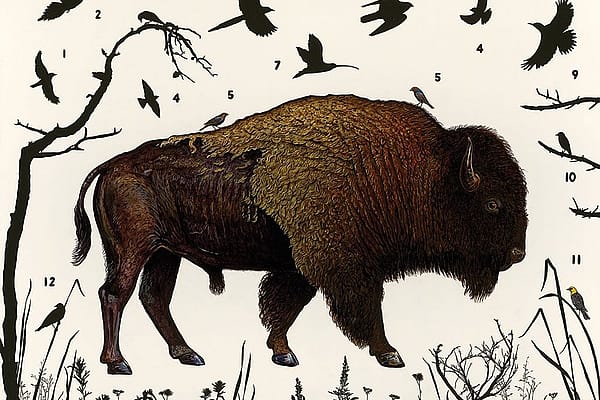

The buffalo has long been an American icon — in art, film, and oral and written history. Many would say that the famed creature has always been, and still is, a national emblem and, particularly, a symbol of the American West.

For thousands of years, buffalo sustained many Native American cultures. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, tens of millions of these animals roamed North America. However, as Euro-American settlers moved west, buffalo faced new and imposing threats. Railroads extended westward, and rail workers harvested buffalo meat hide, diminishing herds and imperiling native populations’ ways of life and main source of subsistence. Things looked dire for the buffalo in the early twentieth century. By 1908, only twenty individual animals were left in Yellowstone National Park.

As the buffalo’s numbers dwindled, some Americans rallied to their defense. In 1905, a group of wealthy New Yorkers formed the American Bison Society. The Society (whose members included William Hornaday, Andrew Carnegie, and Theodore Roosevelt) sent fifteen bison from the Bronx Zoo to the Wichita Reserve Bison Refuge for the protection and propagation of the species. As a result of the efforts of the Society, private ranchers, and concerned individuals from disparate fields, buffalo populations were slowly restored. Today, North America is home to around half a million buffalo, with nearly five thousand roaming in Yellowstone National Park.

One individual who contributed indirectly to the welfare of the buffalo and helped secure the animal’s status as a national symbol is artist Alexander Phimister Proctor. Historically, wildlife conservation has included the work of artists, like Proctor. Having previously sculpted two buffalo heads for the fireplace in the State Dining Room of the White House in 1909, there was no question that Proctor was the man for the job when a sculptor was needed to decorate the new Q Street Bridge connecting the Georgetown neighborhood to downtown Washington, D.C. The four immense sculptures of buffalo that Proctor created were important contributions to the dialogue around buffalo conservation and set in stone – or, rather, in bronze – the belief that buffalo are essential to the character of not only the West, but of America itself.

It seems fitting that the year during which the buffalo’s legacy in American history was formally recognized was the same year in which the Whitney Western Art Museum acquired a 13.25-inch tabletop bronze cast after the model for the colossal bronze statues of the Q Street Bridge, which were installed in 1914. We are thrilled to add this magnificent sculpture to our collection and invite you to come see the handsome bronze in person.

Written By

Elenita Nicholas

Elenita Nicholas hails from the ever-cloudy San Francisco Bay Area but considers Cody, Wyoming her home-for-now as she interns in the Whitney Western Art Museum. She graduated from Georgetown University, with a bachelor’s degree in Anthropology, and will be entering a master’s program in Museum Anthropology at Columbia University where she hopes to specialize in digital media interpretation. As the Curatorial Intern this summer, she is focusing on digital media products - such as creating content for the audio guide, writing blog and social media posts, editing videos, and developing interpretive digital activities - for the Whitney Western.