“When I look at the map [of elk migration], I feel I can see Yellowstone’s beating heart. The routes are the veins and arteries, and the animals the blood.”

-Arthur Middleton, wildlife biologist

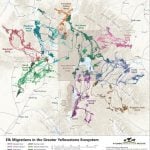

This belief – that animal migrations in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem are essential to the area’s vitality – inspired wildlife biologist Arthur Middleton to expand upon and share his groundbreaking research of Yellowstone’s migratory elk. These iconic creatures, which figure prominently into both tourists’ and the locals’ visions of Yellowstone, travel immense distances over treacherous terrain as a part of their annual migration. Compiling over a decade’s worth of tracking collar data, Middleton helped confirm that many Yellowstone elk travel and live well beyond the limits of the Park for much of the year. The Park’s boundaries, though very visible to us, say, as we pass through the Roosevelt Arch at the Park’s northern entrance, are invisible to elk and other migratory species on their seasonal journeys.

The data Middleton compiled, comprising of the movements of thousands of elk, is featured in the special exhibition Invisible Boundaries: Exploring Yellowstone’s Great Animal Migrations. One component of the exhibition is an interactive map showing the routes of nine major migratory elk herds in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Visitors can adjust the map to dial through different seasons and can selectively display topographic features and man-made boundaries and designations, like borders delineating public and private land. Other visual elements complement the interactive map in the Invisible Boundaries exhibition; these include photography, film, and fine art.

Photographer Joe Riis worked alongside Middleton in much of his field research. On display in the exhibition, Riis’s stunning photographs invite us to empathize with the elk on their monumental journeys in a way that scientific data alone cannot. To capture candid views of these migrations, Riis travelled deep into the Yellowstone backcountry and used camera traps to photograph elk on the move. Ranging from epic to intimate, Riis’s images convey the tremendous feats of migrating elk, as well as the individual struggles these animals face.

Filmmaker Jenny Nichols further expands our appreciation for the magnitude of the elk’s journey through a seven-minute film she produced and which is available for viewing in the exhibition. Nichols’s short film also sheds light on the Invisible Boundaries team’s adventures as they studied elk in the remote country around Yellowstone.

Also within the Invisible Boundaries exhibition is the art of James Prosek. His paintings, drawings, and multimedia works deal with Yellowstone’s animal migrations, specifically, but more broadly address the ways in which humans conceive of nature as something we can divide up, label, and, ostensibly, control. Prosek’s work reminds us that nature doesn’t fit into simplistic categories or conform to man-made boundaries. Rather, nature is interconnected, fluid, and ever-changing.

The combined efforts of Middleton, Riis, Nichols, and Prosek illustrate how the seemingly disparate work of scientists and artists can converge to great advantage. Invisible Boundaries celebrates this intersection among fields and beautifully shows, as only an interdisciplinary project can, that a topic as important and complex as the conservation of great animal migrations in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is best approached from multiple angles.