What Do We Call Art (Which Happens to be Indian)? – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2004

What Do We Call Art (Which Happens to be Indian)?

Rebecca S. West

Curator of Plains Indian Cultures and the Plains Indian Museum

Art is an extremely personal means of expression, saturated with intense emotion, and rich personal and cultural histories. Indian art is no exception. Indian art has always existed amongst the chaos of this nation’s history, but struggles to be recognized outside of very narrow categorizations, even in the present. The question “What is art?” is difficult enough to answer in general terms. Contemporary Indian art must answer to this question, and a multitude of others, as it has been processed, analyzed, and separated as an occurrence that hasn’t merited, until more recently, the title of an art movement as opposed to a division. Examining such categories as well as contemporary Indian art that exists beyond the categories is a step towards ending the over-processing of information in lieu of allowing the art and artists to speak. Indian art exists in a constant state of creative animation as it surges ahead towards its deserved status as art—liberated from definitions and boundaries—but with inherent cultural differences.

Contemporary Indian art is formed from the past and present experiences of cultures very different from the Euro-American cultures that seek to define it. This cultural gap has acted as a barrier, keeping Indian art from being held to the same status as other art. Cultural disjuncture also hinders an understanding of the forces behind Indian art, and encourages or perpetuates categorization. Although Indian artists are the best interpreters of their work, explanation is often left up to intermediaries who attempt to decipher works of art emerging from cultural contexts and artistic traditions diverse from their own. From discordance such as this arises the human need to explain, or order experience—especially in terms of things (such as art) that are unfamiliar: “Humans tend to construct, accept, and share with others systems that explain and organize their world as perceived and known, and feel uneasy without such explanation and organization”[1]. Hence the need to explain, label, and place Indian art in a controllable, familiar context.

Indian art has been the anomaly of the art world, clashing against the strict parameters set by Euro-American art traditions. Rather than dismiss what they or others may not understand, non-Indian art scholars, gallery owners, critics, educators, collectors and curators have historically and presently placed Indian art in its own, separate definition. Art made by Indian peoples, regardless of the style, medium, or purpose, has not appeared in the art historical timeline of this nation. This is despite the presence of the Santa Fe Indian School (which became the Institute for American Indian Arts in 1962), a major force in the education of Indian artists. Indian “artifacts” are discussed within anthropological or ethnographical contexts, however. When Indian art is discussed, it is often referred to as one large category without recognition of the multiple artistic and cultural traditions of diverse groups of Indian people.[2] Additionally, meaning or motivation for creation is bypassed for lack of knowledge of Indian cultures. The art is often romanticized, oversimplified and taken out of cultural context to be judged and categorized with arbitrary concepts as “beauty” and other purely aesthetic qualities.

The categories may be dangerous and limiting, but it is important to understand the motivation behind them. The placement of Indian art in various categories, as well as the failure to acknowledge Indian art at all, stems from conflict between cultures—specifically conflict in terms of economic, ideological and aesthetic goals.[3] Conflict and subordination existed throughout the history of Indian and non-Indian relations, and continue to exist. Artists, dealers, and collectors can potentially profit from the strong demand for art that visually fits into the mold of Indian art, but not without complication and sacrifice:

American Indians who make fine art have found themselves in a real dilemma. Both anthropologists and art historians look for easy references to Indianness—Indian designs, pictographs, or feathers—and dismiss the work for not being Indian enough. On the other hand, fine art critics will look for easy references—Indian designs, pictographs, or feathers—and negate the work for being too Indian.[4]

Often the definition “Indian art” is confining enough, but in fact this art has been diminished further through forced classifications such as “folk art,” “craft,” “primitive art,” or “ethnic art.” Unfortunately, there are still examples of the use of these antiquated and erroneous terms in galleries, museums, and numerous books and articles.[5] The origin of the terms “primitive art” or “ethnic art” with reference to Indian art began in the nineteenth century with mass collecting by ethnographers, who believed they were collecting from vanishing races. By the turn of the century, the art and its makers, branded as “primitive” or “ethnic,” were unwilling providers of provocation to the ethnocentric, argument that Euro-American society had progressed to a higher level. Art and artifacts from Plains Indian cultures continued as objects of fascination after the turn of the century, appearing most often in natural history museums: “these objects signified the rude beginnings of humankind, before history and letters began, when humans lived in nature, without civilization.”[6] The word “primitive” in this instance implies the superiority of one culture over another; that Euro-Americans judge themselves as intellectually, technologically, and artistically more advanced than Indian cultures. Yet the peoples burdened with this misnomer were, and still are, very adeptly surviving and creating art during their own times, places, and cultures. Beliefs associated with these terms became deeply engrained well through the twentieth century, effectively placing contemporary Indian art in the stronghold of categorizations and stereotypes.

Although “folk art” and “crafts” are also used to classify contemporary Indian art, neither accurately defines the vast array of essentially indefinable artwork being created by Indian artists. One of many problems with the term folk art when applied to Indian art lies within the term’s birth: “The idea of a folk and a national heritage became increasingly important in the United States in the course of the nineteenth century, but as ideas they were quite divorced from Amerindians.”[7] From this idea of national heritage emerged a very strong and continuous artistic movement known as “Folk Art.” Its definitions vary, but include, “In simplest terms, American folk art consists of painting, sculpture and decorations of various kinds, characterized by an artistic innocence that distinguishes them from works of so-called fine art…the unpretentious art of ‘the folks.'”[8] Whose version of artistic innocence should be used in determining if art is “folk art,” or “Indian art,” or “craft?” Is it at all reasonable to deposit Indians into the category of “the folk” when their continual artistic presence demonstrates a refusal to abandon artistic and cultural traditions, despite efforts of assimilation? Northern Cheyenne artist Bently Spang comments on the term “folk art” as applied to Indian art:

The term folk art (not to denigrate it), for me implies an unschooled, almost naive form of art.… It also suggests that Native art emerges from a sub culture and is reflective of only regional concerns. In fact, my people, the Northern Cheyenne, are very complex and intellectual, truly a complete culture. The art forms that have emerged over thousands of years tell the story of a highly intellectual culture that moved over a wide area of this continent. Those art forms, now a part of numerous museum collections, had multiple functions dealing with everything from political concerns to spiritual and personal issues. The work of Cheyenne artists today is oftentimes tied directly to our past and is a natural outgrowth of that past. [9]

Relevant questions, and comments, render the categories useless in their attempt to restrict Indian art from any era. They vividly illustrate the destructive nature of the categories to the definition of what it means to be an artist, Indian or not.

Much emphasis has been placed on whether Indian art is “traditional” or “non-traditional” based solely upon how it looks. Implied with the mark of “traditional” is the notion of a static art form. Many examples of contemporary Indian art are based on traditional styles and techniques of beadwork, quillwork, hide painting and other mediums. These traditions are changing, however, with each generation, artist, and personal expression. A man’s shirt by Ute artist, Austin Box, looks similar to historic examples, but is a contemporary piece made in 1989. The shirt is well out of the boundaries set by Euro-American art, but without apology. The artist’s skill and traditional knowledge speaks to his talent and ingenuity as well as to generations of Ute artists before him. Box was motivated to make the shirt after living apart from the Ute Reservation during twenty-one years of military service. Wanting to make a war shirt to wear at powwows, he learned how to construct every detail of the shirt from the quillwork to the beadwork of pre-1880 glass seed beads.[10] If the standard definitions are ignored, this artist and his work can express the cultural and artistic traditions within. Box has created a piece of art that can be used in a literal sense when it is worn, but also used as a re-connection to artistic and cultural traditions. The shirt is an exciting step beyond a static piece both literally—as the shirt moves and changes with its wearer—and historically as a vehicle of expression for a changing tradition.

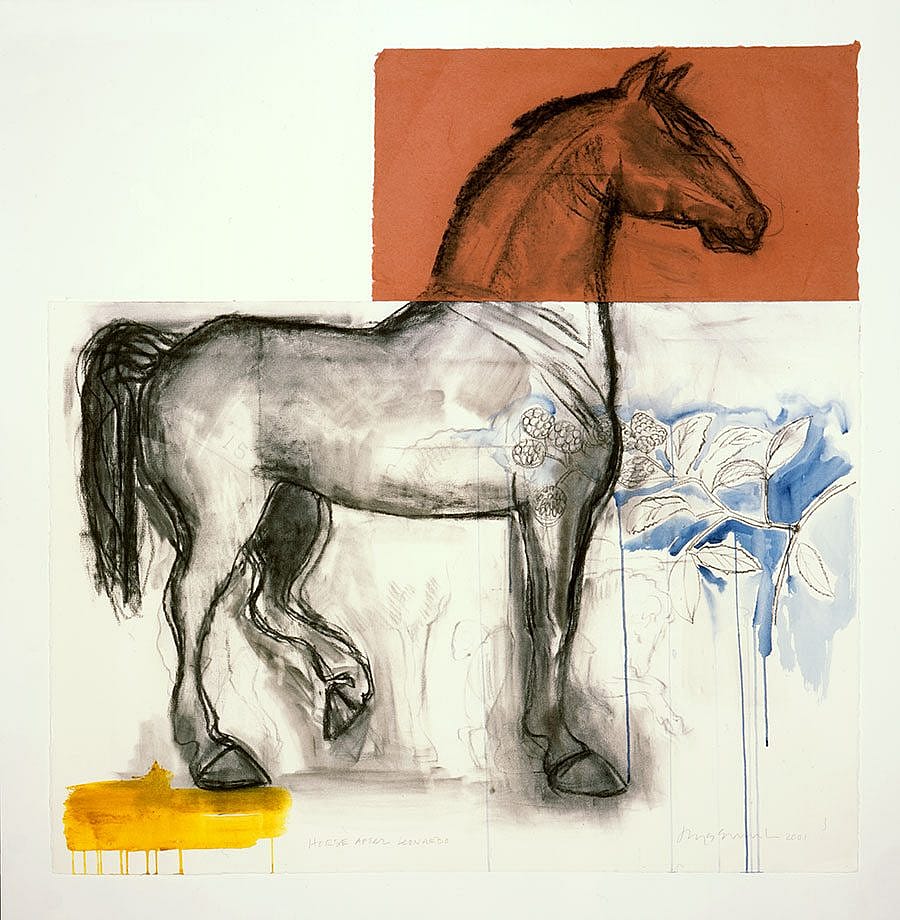

Indian artists have the opportunity to create multiple links between sources of inspiration as they move beyond pre-determined artistic boundaries. Salish-Cree-Shoshone artist Jaune Quick-to-See Smith fuses traditional imagery with a personal artistic styles and techniques that change independently of external expectations. Quick-to-See Smith has been described as an artist who uses pictographic images of animals and landscapes in abstract compositions. Horse After Leonardo is an obvious reference to Italian Renaissance artist Leonardo da Vinci, and is a stylistic a thematic change for the artist. This is not a pictographic image, nor is it a slavish reproduction of da Vinci’s work. A number of theories might be suggested in order to answer the question “why the change?” but one of the most satisfying answers is because the artist can. Quick-to-See Smith has the skill, the versatility, and the freedom to create as she wishes. Biographies list her art as falling into the “Modernist Indian figure-genre.”[11] A jargonized definition says little about the artist, her tribal affiliation, traditions, and inspirations, but essentially compartmentalizes an artistic career in four words. Existing and creating far beyond trite artistic definitions, Quick-to-See Smith relies on forces within, such as her own life experiences and cultural ties, to guide her artistic journey.

Indian artists can express cultural ties in unique formats through non-traditional means. Doing so does not lessen indelible cultural influences emerging from their artwork. Northern Cheyenne artist Bently Spang explains his mixed media sculptures as a recognition of his dual existence: “The materials I choose act as a metaphor for the two worlds I am from, and so illustrate how they are inseparably bound together in me. There exists an inherent tension between man-made and natural materials, modern versus indigenous – one always wants to consume the other.”[12] Within the sculpture Pevah, Spang binds together aluminum, marble, cedar, redwood, travertine, marble and buckskin as a tangible expression of his beliefs and personal history. The traditional materials combine but never quite merge with the non-organic, just as his culture is an influence that is not secondary to his role as a contemporary artist. Spang actively educates the public about the need for Indian artists to be the voice that speaks for their work. He has participated as an artist-in-residence at the Buffalo Bill [Center of the West], and recently led a workshop for Cody High School and Middle School students called “The Artist’s Voice: Mentoring with Masters.”

It is very difficult, if not impossible, for Indian artists to clear the minds of those who are experiencing their creations. Audiences arrive with preconceived notions of what Indian art is, and strong expectations of what they will likely see. While it is unrealistic to expect that individuals will have the same reaction to any piece of art, it is crucial that Indian art is presented with an understanding of its past, its present, and its future to provide the tool of knowledge to everyone who wishes to use it in their interaction with Indian art. An even more important aspect of this knowledge base is the artist’s voice, which should be presented through any means possible—a label, an audio component, or best of all in person along with his or her work of art. To permit a momentary lapse in artistic memory in order to allow the art and the artist to tell all is the greatest justice to Indian art. Theorizing can only go so far in defining an art force whose momentum increases with each artist, each creation, and each generation.

Notes:

1. Ellen Dissanayake proposes that art is a basic human need as well as a behavior in What is Art For? (Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 1998), 197.

2. See Mike Leslie’s chapter in Powerful Images: Portrayals of Native America. (Seattle and London: Museums West in Association with the University of Washington Press, 1998), 114.

3. Essay by Charlotte Townsend, “Let X = Audience.” Gerald McMaster, ed. Reservation X: The Power of Place in Aboriginal Contemporary Art. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, and Quebec: The Canadian Museum of Civilization, 1998), 41.

4. From an interview with Salish-Cree-Shoshone artist Jaune Quick-to-See-Smith. Lawrence Abbot, ed. I Stand in the Center of the Good. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994), 223.

5. “A 1986 display case in Chicago’s Field Museum helpfully educated the public by defining (primitive) ART, DECORATIVE ART, and (miserable thing) NON-ART.” There is also general discussion of the MoMA’s 1984 exhibition “‘Primitivism’ in 20th Century Art.” Shelly Errington. The Death of Authentic Primitive Art and Other Tales of Progress. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 63.

6. Ibid, 5.

7. Dissanayake, 179.

8. Jean Lipman and Alice Winchester. American Folk Art 1776 – 1876. (New York: The Viking Press in cooperation with the Whitney Museum of American Art, 1974), 9.

9. Correspondence with Bently Spang, March 15, 2004.

10. From an interview with Austin Box, March 14, 2004.

11. This information was listed under the “most known for” category for Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s biography on www.AskArt.com (http://askart.com/biography).

12. Sarah Boehme et al. Powerful Images: Portrayals of Native America. (Seattle and London: Museums West in Association with the University of Washington Press, 1998), 115.

Post 153

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.