Indigenous Peoples Day 2016

In 1937, a celebratory event called “Columbus Day” was enacted as a federal holiday, presumably to commemorate the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus. Discovery is a loaded word in terms of Christopher Columbus’ place in history. Let’s look at this carefully and give thought to the myth that most of us were taught (and many still accept as truth). The myth: Columbus was a heroic explorer with three ships who did everyone the honor of finding America, and therefore contributing to the progress and history of this land. In fact, Columbus did not physically land on North America, but instead ran into the Bahamas in the Caribbean. Upon his arrival he encountered indigenous people called the Tainos, whom he misnamed “Indians” due to his belief that he was on the coast of India. Native people already inhabited North America, with languages and cultures established independently from Columbus’ European origins some 10,000 years prior to his arrival. It is estimated that Native populations around 1492 were between two to ten million.

Elevating Columbus to hero status and celebrating his arrival is a painful and erroneous attribution of what really happened once he arrived. The Tainos were murdered, raped, and enslaved by order of Columbus. Disease accompanied the European crews with dire effects for generations of Natives. Columbus was eventually arrested by order of the King of Spain for his crimes and sent back in shackles in the year 1500 (he was eventually pardoned). When gold was discovered in North America shortly thereafter, an unyielding flow of conquistadors followed with similar intent and devastating results to indigenous peoples.

What, exactly, is there to celebrate about this event in history? It cannot be undone, but certainly should be cause for scrutiny and a re-evaluation of what we teach and what we believe.

Although this upcoming day is ensconced in the myths and memories of some Americans, there is hope that we can learn to be better historians and better people by questioning this “holiday.” A move to replace “Columbus Day” with “Indigenous Peoples Day” has taken place in cities like Seattle, Denver, Bellingham, Albuquerque, St. Paul, Minneapolis, Lawrence, Olympia, Berkeley, Anadarko and many others. This action is filtering into our regional communities with news from the Crow Nation that the Wyola, Montana Elementary School student council voted to change Columbus Day to Indigenous Peoples Day. Missoula, Montana, celebrates its first Indigenous Peoples Day this year as a time to honor the “first people to call North America their home.”

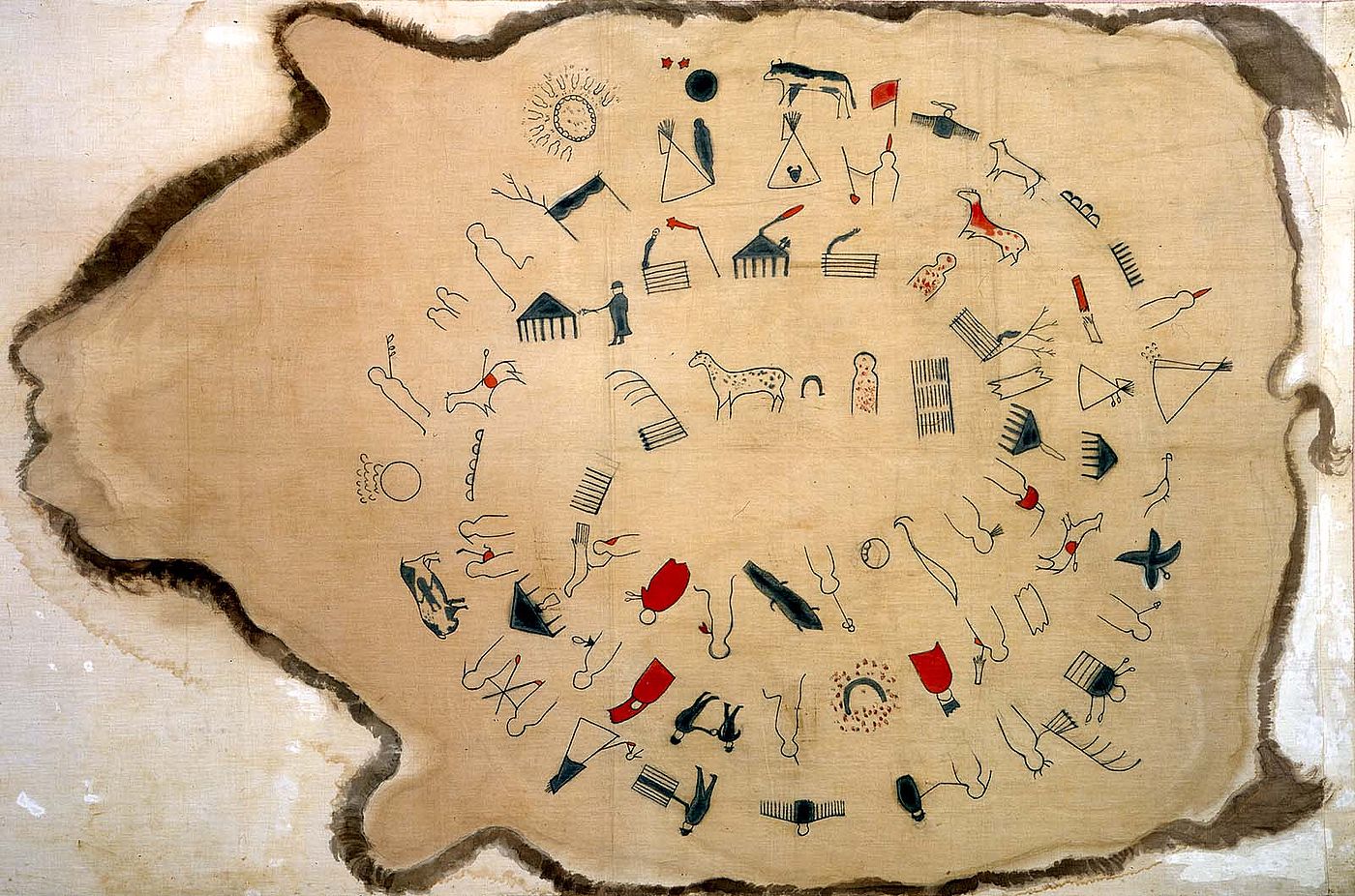

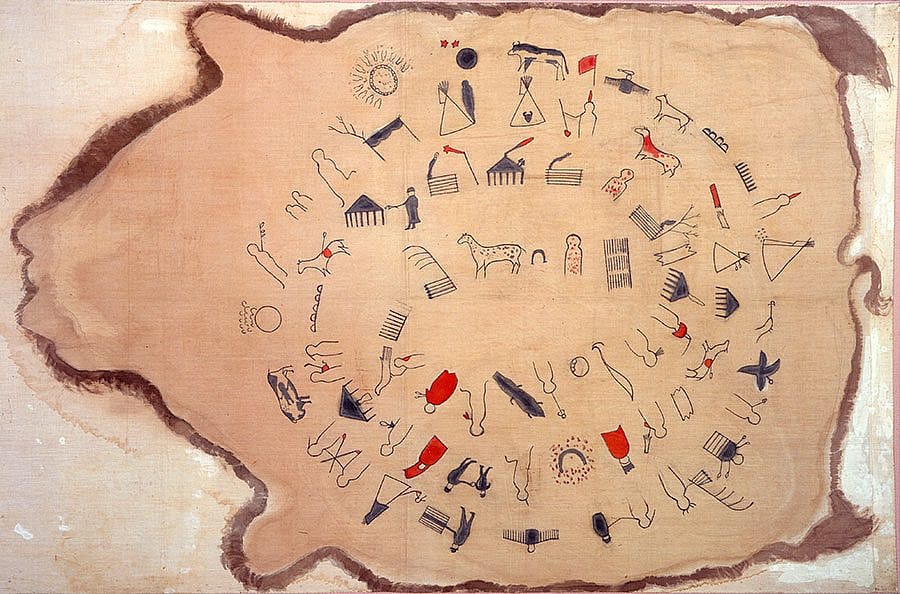

Changes to established names, whether they represent holidays, places, or events inevitably lead to controversy. Such things often represent “tradition” or a sense of permanency and pride. We live in an age where information is readily available to us through primary and secondary sources, often digitally at a swipe of a finger, much more so than for generations past. Using this information responsibly when researching topics such as Christopher Columbus involves looking at a variety of sources not just one voice: publications, periodicals, websites, journals from the expedition, and material culture (aka art and artifacts!). There is nothing wrong with questioning and seeking answers to truths that really are myths.

Written By

Rebecca West

Named as the Center of the West's new Executive Director in April 2021, Rebecca West has served as Curator of Plains Indian Cultures, as well as the Collier-Read Director of Curatorial, Education, and Museum Services. Rebecca has worked with the people, objects, ideas, and programs that define the Plains Indian Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West.