Photographs of Native America – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2000

The Outside Looking In: Photographs of Native America

By Becky T. Menlove

Former Curatorial Assistant, Plains Indian Museum

Printed on postcards, in the pages of countless coffee-table books, and on the high-gloss paper of calendars for the new year, historic photographs that have come to represent Native America are regularly bought and sold. Such popular reproductions occupy a prominent place in the imaginations of the dominant culture, and represent only a small sampling of the vast photographic record of North American Indians made during the late 1800s and early 1900s. Comanche essayist Paul Chaat Smith suggests, “There should have been a special camera invented to shoot Indians…given the tremendous influence photography has had on us. If one machine (the Colt .44 repeating revolver) nearly wiped us out…another gave us immortality. From the first days of still photography, anthropologists and artists found us a subject of endless fascination.”[1]

This fascination is manifested in a photographic record that has become contested terrain-images that can at once offer up visual connections to an Indian past or reinforce mythologies that define and compartmentalize Indian people. Photographs in which the subjects are not identified, photographs that omit or distort context, are photographs that can erase history and perpetuate stereotypes. Such imagery evokes contradictory assumptions about Indians of the past, and in turn influences perceptions of Indians in the present. Scholar Lee Clark Mitchell writes of nineteenth century Natives as subject:

Were they noble savages or bloodthirsty demons, confirmed pagans or redeemable souls, displaced nomads or an abiding symbol of the American landscape itself? The nineteenth century certainly could not decide, and given the collective cultural confusion, it is understandable why so many photographers failed to transcend stereotypes, even when the stereotypes were clearly belied by the subjects standing right before them.[2]

For although Native people have diverse cultures, histories, languages, economies, and worldviews, myriad photographs intended to record their lives have served, and in many cases continue to serve, to sentimentalize, romanticize, and stereotype the Indian of a passing era.

Consider “A Heavy Load–Sioux,” a photograph by Edward S. Curtis. Burdened with a large bundle of firewood strapped to her back, a blanketed woman walks through the snow, her back bent from the weight of her work. In warm sepia tones, the snowy landscape is hazy and undefined. The subject’s face is obscured as she gazes downward, her identity no less clear from the clothes she wears or the task in which she is engaged. While the photograph is lovely to look at-a woman at work, a peaceful winter scene-it presents a type, a popular perception of Indian women in the nineteenth century: locked in time, she seems saddled with drudgery.

In his monumental attempt to record all the Indians of North America, Curtis’s work includes many such “types”—”Winter–Absaroke” is nearly identical to “A Heavy Load”—there is no distinction between the women pictured in these two scenes of winter work. While many of Curtis’s images depict and name well-known individuals such as Red Cloud and Chief Joseph, as many are images of people posed as cultural artifacts. Such stereotypes are perpetuated when these powerfully evocative photographs are reproduced for mass consumption. Artist and photographer Jolene Rickard writes:

The conceptual space of North American indigenous peoples is time trapped…it is no wonder that the mention of Native American, indigenous, aboriginal, or American Indian conjures up Dances With Wolves nostalgia. The visual record of Indian people is mainly one of the outside looking in.[3]

Visually and figuratively shrouded in a nostalgic fog, familiar photographs by Curtis and others often ignore Native memory while replacing it with constructed western myths. For popular audiences, romantic images of “the Age of the Golden Tipi”[4] become an overarching abstraction, a non-Indian vision of Indianness.

Sara Wiles, a contemporary photographer and anthropologist, suggests that difficulties in interpreting historic images of Indians arise because the majority of such photographs lack context. By depicting reenacted events and staged moments, nineteenth-century photographers sought to capture a past that they believed was quickly fading, but the result was often photography that was culturally out of sync.

In her own work, Wiles has made hundreds of photographs of Northern Arapaho. She makes context central to the image and its meaning. In Wiles’s series, Ni’iihi’ (In A Good Way): Photographs of Wind River Arapaho, her subjects are depicted as people-individuals with individual lives. She does all she can to make the pictures personal and always includes a detailed caption and her subjects’ names (“Names are so important,” she says). Wiles tries “to make everything real” in her photographs, knowing that what she brings to the meaning of the image is her perception of the way Arapaho look at things.

The person behind the camera invariably brings his or her experience and worldview to the task, as does the viewer. During the approximately one hundred years that non-Indian audiences have viewed nineteenth century images of Native America, they have continued to reinvent what they see.

Likewise, Native audiences bring Native perspectives to their interpretation of historic photographic images. Complex insider knowledge, memory, and oral histories from within their cultures make it possible to interpret and use historic imagery for their own ends. Julie Lakota, archivist at Oglala Lakota College has found that historic photographs can add important information to historical and genealogical research. Writing about an historic photograph she encountered at the National Museum of Natural History, she notes, “…it helps tell a much larger story, and offers a vital connection to the past…. Family history can be told from the many collections of historical photographs in the museums, the Oglala Lakota College Archives or old photographs at your grandmother’s home.”[5]

Sara Wiles agrees that for Indian people, historic photographs can be useful. She has observed “these days, old photographs get recontextualized on reservations—brought back into the culture and used in new ways…. Native Americans find a lot to like about those old pictures.”[6] Indeed, historic photographs housed in archival collections often provide a visual link to relatives of earlier generations.

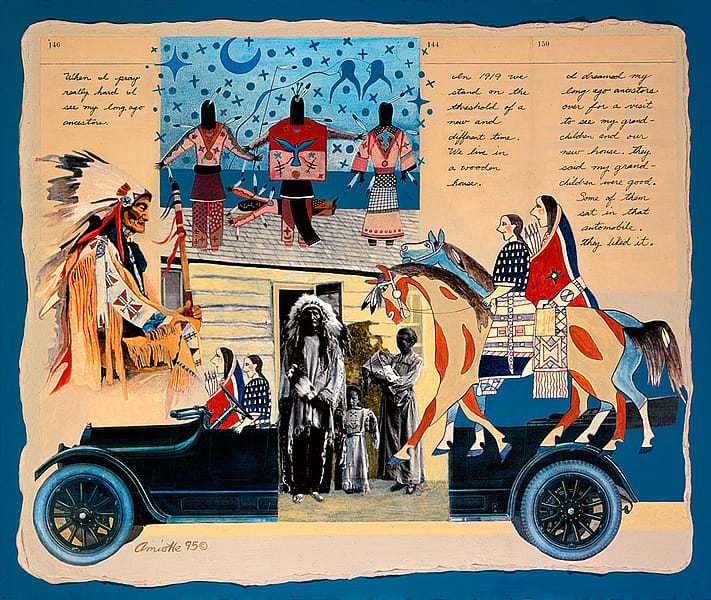

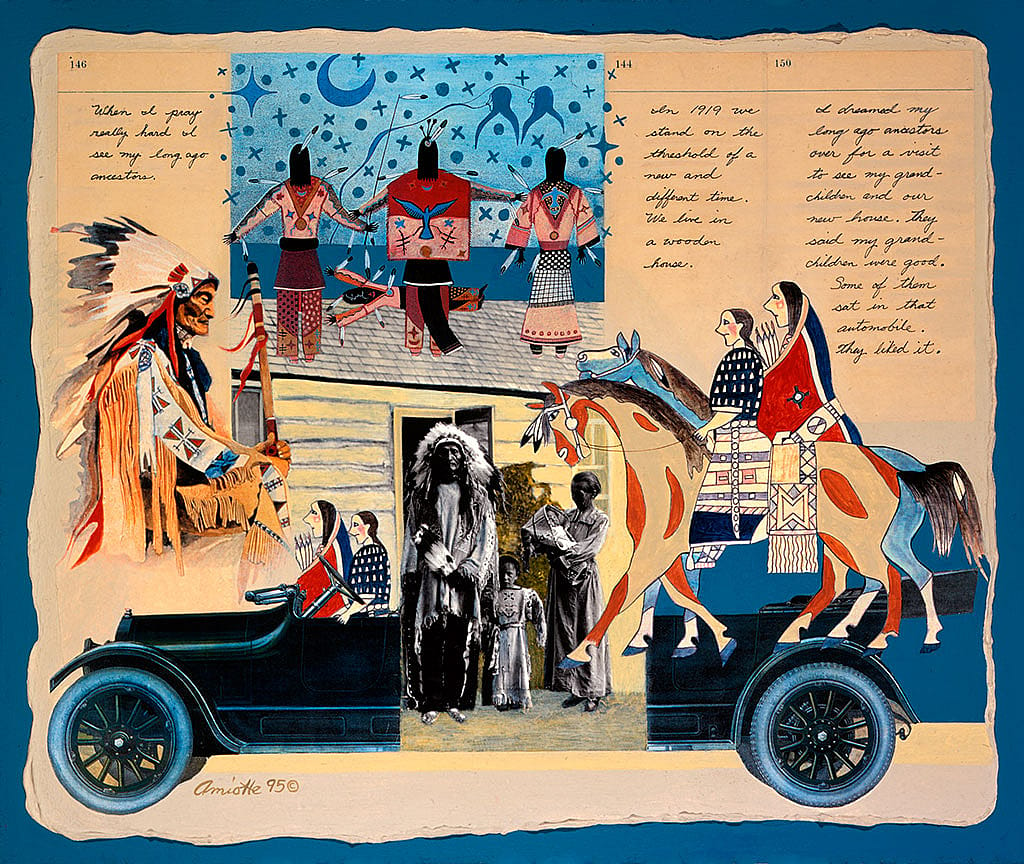

Lakota artist Arthur Amiotte takes this a step further, finding family history and cultural memories in historic photographs of his relatives, images that he interprets and recontextualizes in his artwork. Through the years, Amiotte has collected many photographs of his great-grandfather, Standing Bear, who was also an artist. Standing Bear’s travels abroad, his trip to Connecticut as part of a Lakota delegation, and his time at the home he built at Pine Ridge have all been captured in photographs. Amiotte incorporates these images in his collage work in compelling ways, including both photographic reproductions and his own interpretations of them.

Many contemporary photographers continue to search for the romantic ideal of Indianness they have seen in historic pictures. This search for the “real Indian” in the twenty-first century is inevitably disappointing, since “real Indians” are real people living individual lives. Paul Chaat Smith asserts:

The country can’t make up its mind. One decade we’re invisible, another dangerous. Obsolete and quaint, a rather boring people suitable for school kids and family vacations, then suddenly we’re cool and mysterious. Once considered so primitive that our status as fully human was a subject of scientific debate, some now regard us as keepers of planetary secrets and the only salvation for a world bent on destroying itself. Heck, we’re just plain folks, but no one wants to hear that.[7]

In recent years, greater numbers of Indian artists have “picked up the camera” to begin telling their own stories. Assiniboine photographer, Ken Blackbird brings both his cultural perspectives and a photojournalist’s sensibilities to his photography. He works to capture the vitality of Indian life. Unlike the romantic figures he has seen in historic photographs, he makes images of “life as it should be—the people still holding powwows and ceremonies, and knowing that they always will.”

Blackbird notes that his work is part of a continuum-instead of telling stories on painted hides, he captures history with a camera. When he goes home to the reservation to photograph, he enjoys meeting people, spending time with them, recording these moments on film. Blackbird finds that to take good pictures, pictures that honor his subjects, it is important to follow cultural protocol, even as a tribal member. This can be a slow process, but the time spent brings opportunities to visit and to learn, and often brings the unexpected to the photographs.

In 1993, after several days photographing Victoria Has The Eagle, a woman of advanced age whom Blackbird admired, a cousin dropped by with his little baby in tow. On his way to a blessing for the swaddled child, the cousin had stopped to visit his grandmother, Victoria Has The Eagle. The resulting photographs of Has The Eagle and her great grandchild are some of Blackbird’s favorite images. He says, “the interaction between an elder and a child represents the future…this is real life…I’m not catching souls, I’m catching moments of light.”[8]

While Blackbird works as a documentary photographer for the Billings Gazette—he is one of only about five Indian photojournalists in the country-he crosses over to wildlife and art photography on his own time. He is bound by the landscape he lives in and gets out to photograph whenever he can. “I’m always chasing buffalo and grizzly bears,” he notes. “I look for life and death struggles.” In this symbolic work, Blackbird is “just buffalo hunting…the kill is the photo.”[9]

Camera work among Indian artists brings with it particular challenges, just as the interpretation of historic imagery does. As Smith notes, “Each of us [Native Americans] has a complex relationship with photography, and each knows it. That relationship is one of culture, of history, of politics.”[10] Blackbird suggests that “people like seeing what other people see—seeing through someone else’s eyes.” If we eschew stereotypes, look closely, and listen to Native perspectives, non-Indian audiences may learn a great deal from the historic photographic record. As this record begins to include more images made by Native photographers, new narratives will emerge, through Native eyes.

Notes

1. Paul Chaat Smith, “Ghost in the Machine,” Aperture (#139, Summer, 1995): 7.

2. Lee Clark Mitchell. “The Photograph and the American Indian.” (Princeton, New Jersey, Princeton University Press, 1994): xiii.

3. Jolene Rickard. “Frozen in White Light.” Watchful Eyes: Native Women Artists (Phoenix: Heard Museum, 1994): 15.

4. Rayna Green. Partial Recall. (New York: The New Press, 1992): 59.

5. Julie Lakota. “Putting Names to Faces: The Oglala Lakota College Archives is a Family Photo Album for the Tribe.” Tribal College Journal (Spring, 1995): 36.

6. Sara Wiles. Personal interview, March 31, 2000.

7. Smith, “Ghost in the Machine,” 7.

8. Ken Blackbird. Personal interview, April 6, 2000.

9. Ken Blackbird. Personal interview, April 6, 2000.

10. Smith. “Ghost in the Machine,” 7.

Post 164

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.